Eyes: Novellas and Stories – William H. Gass

Taken together, these stories offer a sample of the methodologies and preoccupations that have defined Gass’s fiction, and the book could serve as a primer on the virtuosity of his language.

This Divided Island – Samanth Subramanian

Divided Island, then, is a post-war book, which tries to saturate its pages with the atmosphere of war.

If creating great historical fiction requires more than an intellectual curiosity about the past but also an appreciation for the nuanced way that history’s shadows accrete to color our present, then Hungarian author György Spiró’s Captivity stands with the best of the genre

Cosmic Pessimism – Eugene Thacker

Thacker’s text isn’t a monument; it isn’t even a book.

Between the World and Me – Ta-Nehisi Coates

Ta-Nehisi Coates does not write to blunt edges. He writes so that it might be possible to slice away the protective illusions that obscure the brutal reality of blackness in America.

A Raskolnikoff – Emmanuel Bove

There are crucial realities here the writing is doing its utmost to convey, realities our realisms can’t confront, realities that require other aesthetics.

The figure of the flâneur is generally a de-politicized one; it is typically a man who observes the world from a safe, distanced, detached perspective.

Bloodletting in Minor Scales – Justin Limoli

The dismissal of “heaviness” from experimental or mainstream quarters alike is an evasion.

The Boy Who Stole Attila’s Horse – Iván Repila

“Small goes on dying for days, and his brother goes on keeping him alive. As if they were playing.” This is Repila’s game, and he’s good at it.

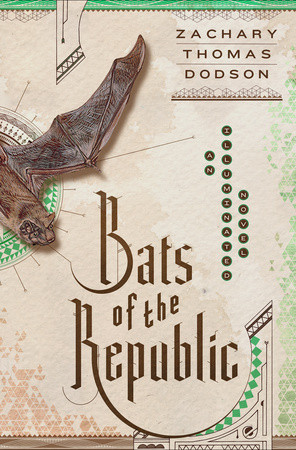

Bats of the Republic – Zachary Thomas Dodson

Dodson seems to ask: why have we left the pages of books so dry when we can do so much?