“The image of war is not communicable,” Ryszard Kapuściński said in Another Day of Life, his eyewitness account of the Angolan Civil war, “not by the pen, or the voice, or the camera. War is a reality only to those stuck in its bloody, dreadful, filthy insides. To others it is pages in a book, pictures on a screen, nothing more.” Thankfully, Kapuściński attempted to communicate the incommunicable. Death, or imminent death, hovers over every paragraph of his report. The stunning simplicity of his observations takes the breath away. The adjectives — “scorched,” “charred,” “burned-out” — are mostly acrid. Adverbs are absent. There are rotting corpses everywhere. The gunfire never lets up. In Homage to Catalonia — another eyewitness account of another Civil war — George Orwell lamented the “lack of non-propagandist documents” that made it so difficult (for anyone, including himself) to write about the Spanish Civil war. To many of my generation these two small books establish a gold standard on war reporting not just because they were eye witness accounts but because they freely admit their biases.

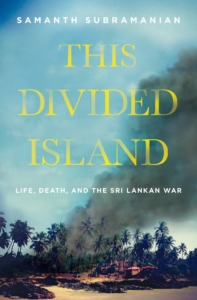

At first it might not seem as if these standards apply to This Divided Island: Life, Death and the Sri Lankan War by the Indian journalist Samanth Subramanian. This is because, as one discovers very quickly, exceptionally engaging though the book is, the use of the word “war” in the subtitle is misleading (or a marketing gimmick.) By Kapuściński or Orwell’s standards, there are no “war stories” in This Divided Island: the author witnesses not a single violent act. Yet it engenders the evocation of those standards because it’s obsessed with war: “there is now no other Sri Lanka for me but the Sri Lanka of its war,” Subramanian admits very early on.

The war in question is the one concluded in May 2009 when the Sri Lankan army visited its version of the final solution upon the separatist group the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam — the so called Tamil-Tigers — who had controlled the Tamil-majority regions of northern Sri Lanka and whose suicide bombers and assassins had dominated the island’s headlines for three decades. In the final push to wipe out the LTTE, casualties (mainly Tamil civilians either trapped in the military operations or corralled as human shields by the Tigers) were counted in the tens of thousands, and refugees in the hundreds of thousands. In 2011, “in the spirit of a forensics gumshoe visiting an arson site,” Subramanian arrived on the island to begin his account.

To bridge the gap between “war stories” and his narrative Subramanian insists that Post-war Sri Lanka is “a country pretending that it had been suddenly scrubbed clean of violence. But it wasn’t, of course. By some fundamental law governing the conservation of violence, it was now erupting outside the battlefield, in strange and unpredictable ways.” Divided Island, then, is a post-war book, which tries to saturate its pages with the atmosphere of war.

In a time of peace (however tense and however tenuous) the conjuration of the atmosphere of war is not easy. And Subramanian’s stumbles are all too visible. When he admits, with a hint of chagrin, that he had begun to see every town “not in terms of its geography, or its vegetation, or its people, but by a Tiger massacre [of the distant past],” the reader might feel that, abandoning his mission of discovery, the author is resigned to rehashing old events. And — during a two-page stretch on life in Jaffna, the political nerve-center of Sri Lankan Tamils — a reader might feel that “inchoate dangers,” the “rank odor of menace,” and any number of “sullen” faces, in the absence of anything more tangible, do not add up to a menacing atmosphere, let alone an atmosphere of war. And some of Subramanian’s gotchas might seem a bit flat. He takes us to a new, opulent Buddhist temple — erected in the memory of a slain Colonel by his family — and shows us a fresco depicting a “radiant” Buddha “keeping at bay a host of dark-skinned savages” (almost surely, Subramanian tells us, meant to depict Tamils). A reader (like this one) who is inured to the waste and ostentation of new temple construction all around India (especially south India) and who has always thought of temple art (new or old, Hindu or Sinhalese) as the last place to go looking for signs of fresh sectarian tensions, might find such evidence underwhelming.

Political developments in Sri Lanka following the original publication may also deflate some of the credibility of This Divided Island. In elections of the last January, Mahinda Rajapaksha — the President — who is unfailingly depicted as a megalomaniacal, Ferdinand Marcos-style despot who was well on his way to a lifelong dictatorship — was voted out of the office which he vacated with little more than a murmur. That Sri Lanka has passed such a robust test to its democratic institutions may affect a reader’s credulity when reading This Divided Island.

The reality about post-war Sri Lankan society remains elusive because details about the final offensive against the Tigers remain elusive and, in the interests of “reconciliation” (an exigency for Sri Lanka according to everyone including John Kerry), may remain so in perpetuity. Tamil, or Tamil-centric, narratives about the three-decade-long strife — from A. Sivanandan’s moving novel When Memory Dies (Arcadia books, London, 1997) to Rohini Mohan’s detailed but shoddy The Seasons of Trouble: Life Amid the Ruins of Sri Lanka’s Civil War (Verso, 2014) — have tended to be unapologetically partisan. On the Sinhalese side, too strident an accusation by the international community of genocide, or too minute an inquiry into why (by UN estimates) forty-thousand had to die to catch a few hundred Tamil Tigers is likely (on the body politic of Sinhalese society) to be tantamount to scratching at “scabs.” In Noontide Toll (New Press, 2014) — a remarkable work of fiction by the master novelist Romesh Gunesekera that can be read as a literary response to the Sri Lankan war — this majority, Sinhalese, sensibility is convincingly explored.

The protagonist of Noontide Toll is a middle-aged Sinhalese van driver named Vasantha whose life story is exactingly and convincingly constructed to place him outside the Tamil-Sinhalese conflict. Till recently, Vasantha has lived only in the south of the island: he can barely follow Tamil, has had little to do with Tamilians, or with their troubled northern regions. Obviously, Vasantha is partly his creator’s doppelganger: author and van driver are about the same age. But we might also see in him the perfect riposte to Subramanian’s “fundamental law governing the conservation of violence.” Vasantha demonstrates no ill will towards Tamils and, far from being a practitioner of the “muscular” Sinhalese Buddhist majoritarianism that Subramanian sees so much of, is even able to summon sympathy for the occasional Tamil war-survivor who crosses his path. Everywhere in Noontide Toll (from vast battlefields packed with scrap metal, to encounters with military officers whose reputations might be of interest to the international criminal courts at the Hague) there are reminders about the costly war. But Vasantha is too busy to really spare much thought for the war. He is either importantly ferrying international businessmen around who have come like bees to honey to bilk the opportunities of the post-war nation, or is relishing the new freedom of being able to zip around an island freed of police check posts and suicide bombers. This is fiction created by a masterful storyteller; it anticipates, if not parries, any accusations of obfuscation or elision. The logic of Noontide Toll is clear: Sri Lanka and its Sinhalese majority have paid too heavy a price to self-flagellate over the events concluded in May 2009. At one point Vasantha wonders how “a small Dutch town [namely, the Hague] . . . on the edge of Europe became the conscience of the world.” This flip-off is directed as much at those who might accuse Sri Lanka of genocide as at Dutch colonial ambitions, the bloody depredations of which in the eighteenth century had been the island’s unfortunate lot.

Others may read Noontide Toll differently. By turning its back on the Tamil massacre, however, it makes its allegiance clear: Tamil readers may say that while it eloquently makes its points, it entirely misses the point. For me, however, it accentuated the achievement of This Divided Island.

The achievement of This Divided Island lies in its dogged pursuit, in spite of insurmountable odds, of a cohesive and non-partisan account of the Island’s divisions. Exactly how divided Sri Lankan society is strikes one about halfway through the book when one realizes that, except for a casual encounter or two, one has not yet met a Sinhala. One begins to wonder how many doors had remained closed to Subramanian, whose name is easily identifiable as Tamil, if not as Tamil Indian. Overwhelmingly, his informants end up being Tamil, and, often, they are embattled members of the Tamil press. But the self-awareness of being a Tamil who is investigating a society that has recently taken care of its Tamil problem sits remarkably well on Subramanian. It accounts for some of the finest writing in the book. He was all too aware that “the truth was simultaneously better and worse than the news in the Tamil press.” He frets that his informants might have “transmitted their anxiety” to him. These concerns address the highest standards of reporting and that alone makes this sweeping study of Sri Lanka’s many divisions an essential read.

This post may contain affiliate links.