Bruno Navasky is the translator of How Do You Live? by Genzaburo Yoshino, a book known for (among other things) being “the first English translation of Hayao Miyazaki’s favorite children’s book.” Bruno kindly agreed to do an interview for the SCBWI Japan Translation Group Blog, where a condensed version of this interview first appeared.

Deborah Iwabuchi: Hi, Bruno! On your website, you introduce yourself as “a teacher and writer in New York City.” Could you add a little to this, especially in terms of translation?

Bruno Navasky: For many years I worked at The Academy of American Poets, where I founded a poetry journal, edited several anthologies of poetry, created the popular website poets.org, edited various poetry anthologies and publications, developed educational programming, and now serve on the board of directors. I also taught language arts and computer science at a tuition-free school in Harlem for more than a decade. My freelance work includes book reviews, journalism, and consulting work in education, technology, and curriculum development, as well as the occasional translation project.

Translation has always been for me less a vocation than a constant avocation. I first encountered Japanese through a childhood friendship with the conductor Alan Gilbert. The two of us studied French and Latin together as kids, and his family took me on my first trip to Japan, where we traveled with his Japanese cousins during their summer vacation. It was an unforgettable tour, from the onsen at Hakone up to the thatched rooftops of Takayama and down to the gardens and temples of Kyoto and Nara. As we traveled, I picked up random phrases of Japanese, and I remember being struck by the many ways in which it reminded me of the Latin works I was reading at the time (SOV word order, for instance, and regular conjugations that create a surfeit of end-rhymes, and thus a tendency to syllabic verse). I was just at the close of that period when language acquisition happens with minimal effort, and I came away with a budding appreciation of Japanese culture and an abiding love for the language.

In college I studied Japanese language and literature, and dabbled in computer programming. People have occasionally remarked to me that the two seem disparate, but it has always seemed to me that coding is very much an exercise in translation, though the object language is a constructed one. I was fortunate to study with Prof. Edwin A. Cranston, the author of A Waka Anthology, a monumental survey of early Japanese poetry. It wouldn’t be an understatement to say that he taught me how to read. In contrast to the classical literature I was reading in some classes, my thesis project was a book-length translation and essay on the work of Tanikawa Shuntarō, a beloved poet who emerged from the wasteland of World War II to write life-affirming poems, playful and soulful, for readers of all ages. (For many years, he also translated Charles Schultz’s comic strip Peanuts for publication in Japanese newspapers.)

After college I attended the University of Nagoya as a research fellow of the Japanese Ministry of Education. Officially I was studying classical literature, but I found myself again drawn to contemporaries of my college thesis subject, the poet Tanikawa. I loved the crushingly precise portraits of parenthood and childhood in the work of Kuroda Saburō, among others, and the richly allusive, surreal and musical poems of Naka Tarō. Naka’s dense mid-career sound poems were particularly challenging from a translator’s point of view. One of the side benefits of trying to translate these poems — and Japanese poetry in general — into English is that one is quickly forced (more quickly, at least, than with prose) to grapple with the impossibility of a literal translation and find one’s own way to what Walter Benjamin called “the task of the translator.”

Shortly after my return to the States, I took a months-long walk up the west coast, from San Francisco, California to Vancouver, in British Columbia. The mother of one of my former students in Japan had given me a small book that I carried with me: Kodomo no Shi, an anthology of poems and poetic utterances by children, collected by the poet Kawasaki Hiroshi, drawn from a column he edited for many years in the Yomiuri Shinbun. Every morning I’d read one of these delightful poems, just as readers of the newspaper did for years. They were simple and direct enough that I could hold them in my head during the day as I walked, turning them this way and that and trying to refashion them in English. By the time I reached Canada I had the seed text for my first book of translations.

Over the years since, I’ve dabbled in translation from several languages, but the only one in which I have an academic background supported by life experience is Japanese. I’ve completed a selection of poems by Kuroda Saburō, another by the German-Japanese poet and novelist Tawada Yōko, who in addition to her novels has written fascinating poems set in the tidal zones between languages and cultures, and a handful of poems and essays by other writers, as well as some business translation. Although it’s no longer an academic pursuit for me, I continue to translate from Japanese as a method of close reading, and sometimes out of a feeling of closeness to a particular work I want to share, and I maintain a strong interest in poetry and all writing about childhood, education, and language.

Let’s talk a little about How Do You Live? It was first published in Japanese in 1937 as Kimitachi wa dō ikiru ka and was then revised after World War II to make it easier to read. It was produced as a manga in 2017, which brings us to your English translation that came out this year by Algonquin Books. Interest in this translation is being propelled by the fact that Hayao Miyazaki, the Studio Ghibli creator, read and loved the book as a child and is making it into an animated film.

Could you give readers a quick idea of what the book is about?

I think at heart for those who love it, How Do You Live? is the story of a boy and his uncle. The boy is learning how to be himself in a challenging world, and the uncle is trying to help him find his way. The boy lives with his mother, in a Tokyo suburb of the 1930s. He has a close group of school friends and together they sail through a series of adventures and misadventures that finally carry him to the stormy seas of a great personal crisis. Or at least, so it seems to him. Throughout the book, both his friends and the adults in his life have important lessons to offer him, particularly his uncle, and those lessons form the framework for what might be considered an ethical treatise by the author Yoshino Genzaburō.

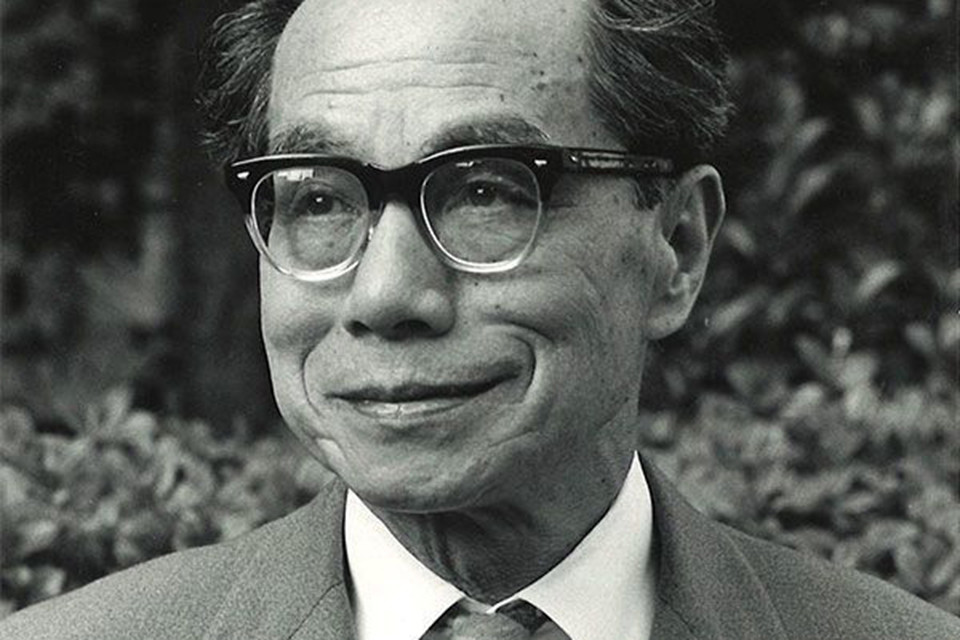

Yoshino himself had been imprisoned for his progressive political associations, and hoped to craft a defense of pacifism, of independent thought, and of the humanities in the face of the rampant militarism, authoritarianism, and censorship of the period. He initially intended the book to be a textbook, one in a series he was editing with a colleague (Nihon shōkokumin bunko, with Yamamoto Yūzō), but partially because of the heavy subject matter, and partially because of the political climate, they decided it would work better as a story. When Yamamoto developed eye problems, it fell to Yoshino to write the book himself.

So in a sense, the book exists on three planes simultaneously: as a work of fiction, as a primer, and as a political broadside. The format that Yoshino hit upon to accomplish this was to interleave narrative chapters about the boy’s experience together with notes that the uncle writes in his own journal. This has the benefit of softening the edge of the didactic material, and allows Yoshino’s own voice to poke through into the story. As an educator, I was impressed with the way the narrative and didactic sections use scaffolding to reinforce concepts after they are introduced — a challenging word or concept is never tossed aside casually in this book, but rather resurfaces and is reinforced in multiple occurrences. And as a reader, as well, I think the book might have been no more than the sum of its parts if the two threads of the book, the narrative and the didactic, had not been knit together, at long last, very neatly in the final chapters, where the book really begins to pull its weight as a novel.

I agree with this. The ending is incredibly moving. Each of the episodes in the boy Copper’s life is pulled together, and the lengthy pieces of advice by his uncle move from broad to very specific. This is where we the readers, together with Copper, are grabbed by the scruff of the neck and dragged out of our rather peaceful existences, with Yoshino demanding to know, “How are you planning to live your life?”

Aside from a brief period when the censors caught up with the book, it has remained in print for nearly all of the eighty-odd years since its publication. Although Japan’s circumstances have changed, and the original text may seem dated in certain respects, the book remains a luminous portrait of Tokyo at a time when Japan was on the brink of profound social changes, a moral beacon that influenced the values of a generation and, I think, a moving story to boot. With the release of the Haga’s manga version and the forthcoming film by Miyazaki, it’s again selling briskly, and catching the eye of publishers around the world.

In addition to its interest as a historical and literary document, I think the book is of particular interest in countries that are grappling with authoritarianism right now. Since the English edition has been released I have had inquiries from Turkish, Russian, and Brazilian translators. I don’t exempt the United States from this, but I also think the book is of great value to the global generation that is coming of age in a time of so much uncertainty — political and economic changes, new technologies, covid, global warming, and so on — and wondering how to live their lives in the face of it all.

How did you get involved with it and what your experience was like?

The American publisher, Algonquin Books, acquired the English language rights to the book after news of the manga and the Miyazaki film caught the eye of Elise Howard, an astute editor and publisher of their Young Readers books. Algonquin knew of my translation work through a previous project with a related publisher, and a contact there suggested me for Yoshino’s book, but I did have to audition for the project. I submitted an initial sample for Algonquin and then an extended sample for the Yoshino estate, which was taking great care to safeguard the integrity of the original text, and had secured certain approval rights. So my agreement with Algonquin was conditional upon approval by the estate, and I had to put in a fair amount of work in advance of the contract.

I had heard of the book, but I had never read it. As I got to know it better, I felt very lucky to have been given the opportunity to do this translation. It ticked all the boxes for me — period and genre, but also it was also a work intended for readers of all ages, so it appealed to me as an educator; and in the midst of the very authoritarian Trump administration in the United States, it seemed like it might carry an essential message of resistance to brute authority and bullying. On top of all that, I have a beloved uncle, and seven young nephews who are already starting to feel the weight of the social and environmental burden we have bequeathed to them, so I could really feel the book. And finally, my father-in-law grew up in Japan during and after the war, so I felt a special appreciation for the portrait the book painted of life at that time.

When I started reading, I felt like it was a book that could have been written eighty-five years ago. It took me back to what I was reading as a child in the 60s, which was books from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Looking back, there was a particular kind of wording that describes and savors every detail of the setting, the characters and the action. It worked to get me inside a story and keep me there, wishing I really was there. As a translator, though, I’m not sure I could have kept up so faithfully with all of those words, although I think it was absolutely the way it needed to be interpreted. Can you talk a little bit about how you adopted a style that reflected the age in which it was written?

The text presents so many interesting translation issues, and finding the appropriate style to locate the book in its period and setting was definitely one of them. I was fortunate that Yoshino was so good at setting the scene: his portraits of Tokyo’s neighborhoods and street culture are so deftly detailed that I didn’t need to nail down the language to a specific decade or even a particular genre convention, only to create the general sense of an older work, and then let Yoshino’s imagery and specifics do the bulk of the heavy lifting. So I wanted to create an impression that the book came from long ago, but not too long ago. My touchstones in English were in large measure drawn from the so-called “Golden Age” of children’s literature, British authors such as E. Nesbit, Lewis Carrol, and Edwin Abbott. These were writers who were all, in one sense or another, border crossers: they moved fluidly between the real world and the world of the imagination, they easily balanced formal and informal language, and perhaps most important, they wrote for both children and adults, bringing their concerns about art, politics, philosophy, science, and even mathematics into their storytelling.

That last quality — shared, I believe, by Yoshino — is often evidenced through an occasional shift in register or voice, easy for a grown-up to read as a sort of winking aside at the foibles of childhood, but, I think, experienced by a young reader as a sense that there’s something more to the story — a deeper truth that requires some digging between the lines to attain. Yoshino is perhaps more explicit about this than the touchstone authors I mentioned; he includes a frame to the narrative in which he addresses the reader directly, with a quiet nod to the adult who may or may not be in the room. In a sense, it’s the bait to a trap: a web of knowledge contained in the book that is itself the bait to a larger trap. (For a similar device, see William Goldman’s opening frame in his novel The Princess Bride.) At other times the shift takes the subtle form of a change from formal to informal language, or vice versa. In any case, it made my job both more interesting and more challenging, as I had to attend throughout the text to these shifts in the narrator’s voice, in addition to the individual voices of characters in the book, children and adults of various social classes in Tokyo of the period.

Of course, the gradations between formal and informal or intimate language are far less explicit in English than they are in Japanese, so to a certain extent I flew by the seat of my pants, moving between language of greater and lesser intimacy, and greater or lesser levels of narrative distance to try to recreate Yoshino’s gentle humor and slightly archaic tone in English. Similarly with the shifts between simple narrative and the quite technical economic, philosophical, and scientific descriptions in the uncle’s interleaved notes. Which is not to say I didn’t agonize over specifics here and there. Throughout the work I was helped by my editor at Algonquin, who maintained a clear vision that the English version needed to be coherent for younger readers, without sacrificing the unique and idiosyncratic format and style of the original.

I confess that the Miyazaki connection is what grabbed my interest at first. Written in the late 1930s, I imagined this book would have a critique of Japan’s militaristic road to war as its theme, something Miyazaki has used in a number of his films. Outside of the story of Napoleon, though, How Do You Live? actually doesn’t have much about war, though war could be the elephant in the room—we can smell it and hear it stomping around without actually seeing it. I greatly appreciate your historical notes at the end of the book; they answer the questions I had as I read.

I came away from this project with an immense respect for Yoshino and his work. It took courage and determination to do work like this at the time he was doing it. Not only did he become a key figure in the history of one of Japan’s great literary and educational publishing houses, but he went on to a lifetime of work devoted to pacifism and the humanities. I’m a huge fan of Miyazaki’s films, and I can’t wait to see what he makes of How Do You Live?, especially given his childhood response to the book, and I’m certain that his interest accounts for the surge in sales of the book, but I believe the reason that it’s still in print goes deeper than that. The school where I was introduced to language study (as well as math and science, art and music) was the Ethical Culture School, which also trains students in ethical philosophy from elementary school onward. We were taught to think carefully and come to independent conclusions about what is the right thing to do as we live our lives, and — while recognizing and honoring the importance of Yoshino’s work for peace — I can’t help but feel that the importance of independent thought itself must be his central message in this book.

I had such a great time doing the research for this translation, partly because of the period in which it was set and partly because of the eclectic subject matter. Ordinarily, I’d be inclined to do a first reading of the book “cold,” just to get to know it directly before touching any biographical or critical material, but because my publisher wanted some background on the author and publishing history of the book, I began with that, and then dug into the text. I think I said something earlier about the differences between translating poetry and prose. With poetry I’m ready to let the Japanese have its way with the English more often than not, and my first drafts are usually in very fragmented, fractured English, as close to the Japanese vocabulary and word order as I can come, because I’m more worried about getting locked into conventional English phrasing, not at all concerned about “breaking” the English, and want the draft to point back at the original as much as possible as I get to know it better. But in this case I was very focused on the overall tone in English, and the specific voices of characters, so from the first draft I was looking for my English phrasing, and to keep the work in sync with the original I just kept really extensive notes.

I had three sets of notes. The first were the classic “academic” notes, about 30 pages of notes and sources on names, dates, places, mostly historical. These included authors and books of personal relevance to Yoshino that he references in the text of this book, but also links to real historical images or video of things described — period hairstyles, neighborhood streets or temple grounds, a specific painting or postcard. When I was a graduate student, the internet was pretty primitive and real translation work often required travel to local libraries, but now, I have to confess I’m amazed daily by how easy certain tasks have become just by typing a few words into Google. Then there are other things I just got lucky with — for instance, some quotations from the French philosopher Blaise Pascal that were unattributed in my working edition of Yoshino’s book, but which I just happened to recognize from my school days.

My second set of notes were all on specific translation issues that needed to be addressed. Some were perennial, such as how to handle measurement units, currency, etc. Some were technical, verifying some of the technical vocabulary from the book (economic terms such as “relations of production,” or the difference between “gravity” and “gravitation”). Some were broadly culturally specific (which Japanese words to transliterate, for instance, instead of translating) and some were very specific to this text (such as the nicknames of the book’s protagonist, Koperu and his buddy Gatchin, or how to handle an associative etymological discursion on the word “arigatai.”

My third set of notes consisted entirely of lists of words or phrases, usually ones that appeared repeatedly in the text, or sometimes related groups of different words, and lots and lots of page references. These involved questions of nuance and precision, sometimes of tone, and places where I needed to be consistent across broad sections of the translation. This is, I think, another difference between translating poetry and translating a novel, and will probably be very familiar to your blog readers who have more experience with the latter. It’s hard to ensure consistency across a longer prose text without creating a sort of working concordance to track these. That’s not to say that you always have to translate the same word the same way in every instance, but if you’re going to diverge from that principal, it’s good to know you’re doing it, and have a good idea of why you’re doing it.

So the second and third sets of notes were largely “notes to self” and much of the work I did during the middle sets of revisions revolved around them. In the end, because Algonquin envisioned a broad readership and not an academic audience, we didn’t include any of the notes in the published book, and occasionally amended the text to add clarity in lieu of footnotes, but all the notes were an essential part of the working process.

The suggested ages for readers of How Do You Live? is ten to fourteen years. I imagine fourteen-year-old readers can digest most books, but some of the wide-ranging advice Copper’s uncle gives him was a little beyond me, although when I stuck with it, there was quite a lot to learn.

I can’t disagree with you about that, and Yoshino himself says as much in his foreword to the book. There were also moments when I couldn’t help being irritated with this schoolbook of an uncle, and his sections reminded me at times of the proletarian literature in the years immediately preceding Yoshino, but his sincerity always won me over in the end, as did the uncle’s love for his nephew — and I do think the lessons were brilliantly selected to educate both in their eclectic fields and simultaneously as cogs in the powerful ethical argument Yoshino was building. I love the way the many disparate parts of this book seem to be in a bit of a tug of war, but then are knit together in the end. Ultimately, I think that this book may not be an ideal book for every reader (as if there were such a thing!), but it is an absolutely essential book for some special readers — those who are able to see its magic.

Deborah: I agree with you about the magic, but reading all the way to the end is the best way to find it. I do hope that readers of all ages will pick it up, and find out why Hayao Miyazaki loved it so much.

Deborah Iwabuchi, graduate of Callison College, University of the Pacific and longtime resident of Japan, has translated novels by Nobuko Takagi, Miyuki Miyabe and Jun’ichi Watanabe and co-authored Autobiographies by Americans of Color, 1995–2000. She enjoys blogging on children’s books in translation. Deborah works out of her Minamimuki Translations office (https://minamimuki.com) in Maebashi, a beautiful town just far enough away from Tokyo.

This post may contain affiliate links.