[University of Georgia Press; 2023]

“If there are any clouds overhead / that day, I don’t notice.” Writes poet and nature lover Ariana Benson, “But I do note the scored plot / of my palm; its dark brown verso, in the sun turning darker, / as it begs questions of this land, its history, my play / upon it.” These lines from Benson’s poem “Cruel Ripening” highlight the tensions in writing nature as a Black observer. Ariana Benson, a self-described Southern Black ecopoet, hailing from Chesapeake, Virginia, extracts history from the land and places it on the page. In an act that can best be described as rememory, Benson writes of her background as a Black child, fascinated by and inundated with the natural environment.

A field can be described as an open, unbroken expanse of land, land containing a natural resource, a place where a battle is fought, an area constructed for human activity (usually competition), or an area or division of an activity, subject, or profession. The field, as site of inquiry, begs attention, attention that author Ariana Benson craftily imparts through ekphrasis and ecopoetic inspection. Navigating the capacious duality of Black/nature relations, Black Pastoral, Benson’s debut poetry collection, ponders both the violence and majesty of various fields. The poet envisions history as a living, breathing entity that we are both beholden to and shaped by—this is not just swaths of greenery, but land that has borne witness to, and evolved around Black suffering. Black suffering is treated as a natural resource, one that is harnessed to capture and extract other natural resources. Here, amongst the grasslands and the cicadas, is a semi-dormant battlefield. “Finished coughing out the past,” Benson writes in one poem, “the new man stills.” But, as Benson demonstrates throughout the collection, are we ever truly finished coughing out the past? Why do we insist on rendering outdoor spaces empty when they are filled with so much mourning, and so much joy?

It is through these multilayered musings that Benson crafts a novel field of study within the pages of Black Pastoral, ruminating on various bonds between Black people and nature. The pastoral is generally defined as an agrarian landscape, but in poetry tradition, is a poem that romanticizes idyllic country life, withdrawing from the ills and burdens of modern living. But pastoral poetry, particularly as it relates to the American landscape, relies heavily on the removal of Native and Black populations, often glossing over the history that makes these landscapes so “idyllic” in the first place. Black Pastoral deromanticizes the American landscape, instead positioning it as both a source of violence and refuge for members of the Black diaspora. By consistently invoking Black presence across time and space, Benson insists that the reader must hold these multiple truths to really engage in world building: “what new life can there be / without forgetting / those given over / to flame?” Invoking the dawn of a new world in “aubade after earth,” Benson challenges the reader to link Black pasts to Black futures, to lament the planet we have bruised in order to envision the planet we are moving towards. Black Pastoral confronts the endurance required to live among constant erasure, bearing the cost of remembering, capturing how easily memory is erased from the land as the land turns itself over, nevertheless urges us to resist this erasure.

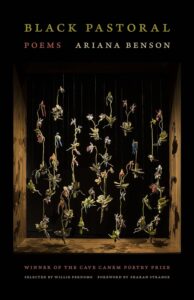

Benson’s attention, her practice of deep listening and deep observation, is what makes Black Pastoral so compelling. Filled with ekphrasis, Black Pastoral dives into the sensorial experience that is nature: there are no stagnant landscapes or images, but ones filled with life, dynamism, and as Benson herself describes, “playgrounds for memory.” Even before opening the collection, the reader is drawn in by the cover, depicting a suspended glass-blown flower installation by Debora Moore. Moore’s art itself is a meditation on the power and mysticism of nature, lending Black Pastoral yet another intense form of witness.

Synthesizing Black knowledges across time and space, but forever rooted in the lush greenery of the South, Benson slows down and demands that we, the reader, observe with her. Benson’s writing refuses distance: we are as much observers as participants in these tensions of kinship, land and spatiality, giving us a newfound sense of self positioned against history. The reader is enveloped in the presence of boll weevils, crickets, swallowtails, lizards, wildflowers, longleaf pines, riverbanks, all of whom bore witness to Black pain, but who are nevertheless a source of majesty and possibility among these wounds. Saturated with vivid imagery, giving voice to both the human and nonhuman, traveling from Ghana’s Cape Coast, to the Great Dismal Swamp to North Carolinian fields, to numerous still-life paintings, to a world not yet articulated, Benson weaves Negro spirituals to bird song, singing liberation across time, species and space. It is within this expansion that a “Black field” is reborn, an area where our presence is both intrinsic and necessary: “I know I must sound mad. I hope I’m the kind / Of mad that makes you feel most whole. / Think how, when we’re sun-pruned and weary, / We’ll stroll here, among the wayward blossoms. / How right—to love in a field of our own making” (“Love Poem in the Black Field”).

Repetition, and other invocations of the field, create the lyric that is Black Pastoral. Through both craft and visual imagery, Benson observes how terrors evolve with the time, layering humans, the planet, and society, noticing how we inform and bump up against each other. Each section titled “Black Pastoral” engages in clever world play, highlighting specific words in bold for thematic emphasis: “Black Past,”and “Black As,” creating a multidimensional exploration of Black life. Benson’s recurring poems titled “Love in the Black Field” insist on the presence of Black self-articulation, even in moments of terror. In the Black field, grief and loss are not separated from love, but interrelated through a faith that glimmers in these poems. Encapsulated by wonder, Benson returns to the field time after time, calling up spirits of ancestors, lifting them in gratitude and prayer. Her invocations fuse memory onto the land, insisting on Black presence.

“What came before?” asks Black Pastoral, time after time. “And what can we make of it next?” The reader is surrounded by inheritance: Benson is writing in a long tradition of Black poets observing the natural world. Authors like Lucille Clifton and Terrance Hayes (from which Benson invents her own form, the Golden Spade, a child of the Golden Shovel), are called in as Benson reflects on her own experience being a Black person enamored with and inspired by nature. Every page opens the possibility that we will find our own narratives situated on the land. Benson’s poems act as a guide towards deeper compassion and further inquiry: What lands are we not seeing? How has our own vision been shortened? What happened before we came, and what we will leave after we are gone?

Even things that appear empty are not so; they are overflowing with stories, bursting with memory. Benson’s collection ends here, leaving her reader with deep yearning, but blessed with a full belly to fuel that desire.

“They know to freeze, to still their limbs, wait for the melt, / for the trees to weep the winter out—the silent sobs a prelude / to the red, not of end, but of moss. / Of possibility” Benson writes in a poem that shares the collection’s title, describing the forever cycle of tree resplendency and dormancy. As we stand in our various fields, Benson invites us to interrogate their function, how we have been influenced, how we might influence future worlds. What is left to do? Exhale, shed, then begin again.

Ashia Ajani is an award-winning storyteller and environmental educator hailing from Denver, CO, Queen City of the Plains and the unceded territory of the Cheyenne, Ute, and Arapahoe peoples, now living in the Bay Area, unceded Ohlone land. Ajani has received fellowships from Just Buffalo Literary Center, SF Museum of the African Diaspora, and Tin House, among others. Their debut poetry collection, Heirloom, was released in April 2023 with Write Bloody Publishing.

This post may contain affiliate links.