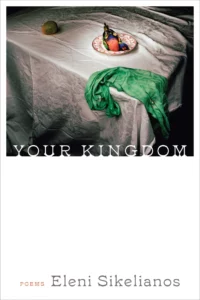

Daniel Nemo talks to Eleni Sikelianos about her latest poetry collection, Your Kingdom (Coffee House Press, 2023), which invites the reader to explore the complexity of the human evolutionary timescape. The poems offer a multifaceted portrayal of our relation to all forms of life, urging us to reflect on the responsibility that our consciousness of self demands towards them.

By shifting the center of gravity away from the human element and onto this kingdom’s “waves of wild energy,” Sikelianos’s visionary ecopoetics allows a whole new language of life to take shape in what she calls the beyond-world of the poem, a space where one can “let the body feel / all its own evolution / inside.”

Daniel Nemo: I want to open by saying that your new work, Your Kingdom, is a tremendous book, which seems to pick up the thread from Make Yourself Happy. Given your fascination with microbiology and oceanography, is this the book you always wanted to write, the one that almost had to be written?

Eleni Sikelianos: Thank you so much for your close reading of Your Kingdom! It seemed absolutely necessary to think about other species and our connection to them, to tend to these connections through thinking and writing about them, so it did feel like a book I had to write.

It’s definitely in the lineage of Make Yourself Happy, and also maybe even more directly one of my early books, The California Poem (2004). All three of these books are deeply engaged with humans, more-than-humans, and our environment, with different concerns, forms, and sounds foregrounded in each. Many species and biomes are invoked in The California Poem, and there is a lot of oceanography in it. (I love thinking about that word as literally “ocean writing.”) It’s a book more firmly rooted in place than the others (as the title so boldly insists), and is in a way reckoning with the coming into being of a consciousness (mine) as shaped by a landscape (California’s). Your Kingdom follows from that in its use of scientific bodies of knowledge, but is in a mode of questioning how these epistemologies came into being and the damage those processes have caused—while still reveling in the wondrous windows scientific inquiry offers into all that is around and inside us.

After sitting with the grief I was called to be attentive to while writing the species extinction series in Make Yourself Happy, I felt an urgent need to write with more-than-human animals in ways that felt celebratory. We can’t erase the eco-grief that is now a part of our daily living, but meditating on the ways we’re carrying other species around in our very bodies was frequently joyful.

Can you trace the curve between To Speak While Dreaming and Earliest Worlds, The Book of Jon and The California Poem, Body Clock and Your Kingdom? How does it all come together?

There are a lot of different threads here, but there are also some ongoing concerns. The main, most important one is the space of the poem or piece of writing (or art) as a potential field of liberation. For me, the poem is the place I experience language as freedom. That doesn’t mean it’s not also tethered to the world, but it gets to fly in all kinds of other wild spaces, beyond-world. That is the ragged flag of poetry.

The hybrid prose/poetry/image works (The Book of Jon and You Animal Machine, thus far) are engaged to some degree in that too, but they are also engaging in sense-making, not in terms of logics, but in terms of picking up the threads of tattered lives and trying to create a weave from them, to give my ancestors and my thinking about them a place to live.

One of the ways these two hybrid books (there’s a third on the way), all of which deal with my family, meet the ecopoetic work is in their thinking about relation. I’m interested in lineage on so many levels—patently not in the patriarchal or colonial sense, but as a method to think about how we are in relation to what has gone before us and what is around us now.

Seems to me your new book, as do your previous ones, succeeds in keeping language open, like Alice Oswald says, “so that what we don’t yet know can pass through it.” How do you manage that?

I can’t quite say how I tap into that space, but I can say that it’s a value to me, so that’s the start. I can sometimes feel myself over-groping for meaning, and I know that’s a space where freedom gets curtailed, so I try to check that.

In the opening poem, you write, “Biology, like language, is remembering. What life is is your cells / remembering what other life did before it. / And even further.” There is undoubtedly a linearity to time that you explore in the book, tracing our lineage back to its origins. Yet you also seem to find that we evolve in a world where past, present, and future are intertwined in an all-at-once multidimensional timespace. I’m thinking here of these lines: “you find yourself in a crux of time, connected by memory / to the past which / is the world / or / to the world, which is the past, and the shape / of the future went weirder than ever.” As the book came together, did you feel at times that language—poetry—may sometimes be remembering the future?

Yes, absolutely! Poems are cast into the future and into the past. When we read someone like Emily Dickinson or William Blake, when we hear Maria Sabina chanting her poem-veladas, we feel that. Poetry, poetic language, exists in a temporality that both engages all measurements and is beyond telemetry. The very line break enacts that—when, at the end of each line, we fall into the unmeasured blank space of the page, where the human time of language is for a moment suspended. And any time we’re engaging in an ecopoetic or “poethical” gesture, we are remembering the future in language.

How does crossing the line between one’s own body experience and the non-human (or the natural world) expand the poem’s sense of possibility?

Well, I suppose at the most important level, the attempt to think-with-others expands the possibility of consciousness. It’s a consciousness-expanding act. Did you ever hear about the consciousness-raising events in the 60s and 70s? I was just a baby when that started, but I suddenly like the idea of thinking of it like that.

What is it like to be a bat? The philosopher Thomas Nagel asks that question in his essay of the same name, and he sort of comes to the conclusion that the only way to know is to extend the imagination into the possibility of knowing. There are a couple of important conclusions to draw: Humans will never know what it’s like to be a bat, but 1) that doesn’t mean bats don’t have consciousness, and 2) we have to engage a poethics of care when imagining what it’s like to be a bat. Part of what we have to hold, while imagining it, is the impossibility of knowing what it’s like to be a bat. Otherwise, we get into the more abject territories of anthropomorphism. I am not against anthropomorphism, I think it’s an impulse that can be reclaimed, but with a difference, and part of that difference involves respect for other living beings’ otherness.

One of the problems I kept coming back to while writing Your Kingdom was the human obsession, which we see in poetry, philosophy, and science, of identifying what makes humans different from other animals. This is a real stumbling block, and has opened the doors to all kinds of misdeeds. It’s time to turn the whole inquiry around: How are we like other living and beyond-living beings?

One gets a sense when reading “Your Kingdom” (which stands as one long poem that makes up the second part of the book) that time is at once accelerating and decelerating in your writing. You trace the history of evolution from sea to land in a few pages, yet pause to observe the detailed features of various creatures, as if poetry was the magnifying glass through which all life should be seen. Was this double tempo of the book your way of celebrating the world while sounding the alarm about its precariousness?

I like that you experience it as a double tempo! Super cool. I’ll have to think about that, but I was definitely aiming to both celebrate and sound the alarm. The double-tempo notion is interesting to contemplate in terms of the form of the title poem, because I was sometimes working with the double helix of DNA strands in mind: how they fuse, split, exchange scraps. You might be able to see that on some of the pages. I was also working with enjambments that jump across double-meanings and stanza breaks (with lots of blank space between), as a kind of leap in possibilities of being, echoing evolutionary or genetic somersaults and gaps. Maybe your sense of acceleration and deceleration is also related to these formal signatures, since they are disrupting the ways we expect language to occur in time.

Do the poems come out of a spontaneous production of cinematographic, let’s say, images occurring in the mind’s eye, from the sonic and visual interplay they give rise to, or from more language-configured channels?

Hmm. All of the above. As well as thinking, feeling, and lots of research.

One of the many lines that resonated with me long after I finished the book was “I wanted to tell you / how you still have to carry / the sea around inside you.” Throughout the collection you make a point to draw on our interconnectedness with all forms of life: “you go dizzy from the deep / expanse of it—how to find yourself / in space in such an / animal carnival . . . you can’t start from scratch, can / only build with what others built before you.”

Are humans small, insignificant beings in your poetic kingdom, or does their complexity pertain to their endless interlinks with, and inheritance from, other species?

I wouldn’t call us small, insignificant beings, but I wouldn’t call a bee that either! What’s important about us is our endless interconnectivity. What’s tragic about us is our failure to honor that species and environmental connectivity in our governmental, economic, religious, and educational structures.

“If I look up the World (appears),” a line you continue with Google’s entry for “World,” sensitively combines nature and technology—two systems that seem at odds, the harmony of the former so often disrupted by the latter. Your poetry creates such a sense of wonder (you write, “you’ve a whole world to explore”) that it is impossible for the reader not to look around with a renewed sense of hope and astonishment. Yet you also warn of the perils of our behavior: “extinction is a central feature of your model / you went wild with it,” and even urge us to consider: “And you ask / unabashedly, if / EYE NOT CREATED / BY GOD / what / could save all this . . . / can you do it / without destroying / all of us?” Are life and the natural world, and implicitly our fate, chronically interlinked with technology and artificial intelligence in these times of human recklessness?

The short answer is yes. Part of the long answer involves recognizing that we are not as powerful as we think we are, that the world (whatever that is) will go on without us.

Interestingly, in the glossary that concludes the book, you play with the etymology of “kingdom” and mention that you “choose the roots that go through “kin,” and lead away from “doom. No king in this kingdom.” You refuse the classification or hierarchy that a kingdom implies. Is this what you see as the role of poetry—to disrupt established systems and create alternative, more harmonious dimensions for us to live in?

That seems like a pretty good summary! Poetry has many roles, and disrupting established order and creating alternative modes are a couple of the important ones. It’s also here to keep us awake to the sensory experience of what it feels like and means to be alive.

Born in California on Walt Whitman’s birthday, Eleni Sikelianos is a poet, writer, and “a master of mixing genres.” She grew up in earshot of the ocean, in small coastal towns near Santa Barbara, and has since lived in San Francisco, New York, Paris, Athens (Greece), Boulder (Colorado), and Providence. Deeply engaged with ecopoetics, her work takes up urgent concerns of environmental precarity and ancestral lineages. Your Kingdom (Winter 2023) will be her tenth book of poetry, riding alongside two memoir-verse-image-novels.

Daniel Nemo is a poet, translator, and photographer, and the editor of Amsterdam Review, a literary magazine. His work is forthcoming or has appeared in RHINO, Dream Catcher, Brazos River Review, Off the Coast, Pennsylvania Literary Journal, and elsewhere.

This post may contain affiliate links.