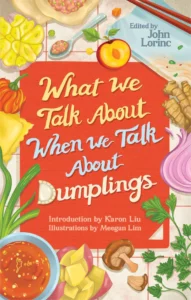

[Coach House Books; 2022]

A mix of personal essays, historical commentary, and the occasional recipe, What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings is an anthology edited by Canadian journalist and urbanist John Lorinc. Compiling an anthology about possibly the most common food in the world practically guarantees an interesting mix of histories and perspectives, which What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings delivers. However, through no fault of the individual contributors, the book falls short of the potential of its subject.

These essays have one overarching lens: personal. An anthology about dumplings that’s largely personal essays is not a bad thing; it’s quite lovely, in fact. The individual essays are warm and well-considered. For André Alexis (“Solid, Glutinous, and Toothsome”), dumplings symbolize an accessible food, allowing him to connect to a childhood culture from which he felt distant. Eric Geringas’s “The Knedlík, Warts and All” uses the dumpling to vividly situate the reader in early 1990s Prague. Miles Morrisseau’s “Métis-Style Drop Dumpling Duck Soup” is an affecting family history. Finally, Bev Katz Rosenbaum’s “The Case for Kreplach” makes artful use of the personal essay to advance an argument for the superiority of kreplach, a traditional Ashkenazi Jewish filled dumpling, over matzah balls. It’s a perfect use of the form. It would be a fool’s errand to argue that kreplach are superior to matzah balls in the absolute, but Katz Rosenbaum sure can argue that they’re superior for her, and she does so compellingly.

Still, while the individual essays are well-executed, personal is not the only lens through which to discuss the dumpling. I will admit that I had a misconception of this book before reading it. This was largely due to a neglected webpage: before my copy of What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings arrived, I had read the table of contents on the book’s website, not noticing that it was “tentative.” Per that table of contents, the book would contain seven essays on food history and another six on cultural history. While many of the entries in the non-tentative What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings provide some historical background for their dumpling subjects, I would be hard-pressed to call most of them history essays. (Case in point: One of the authors initially billed under “cultural history” is Kristen Arnett, who contributed a very good humor essay on how everything is a ravioli, including bananas, mattresses, and your girlfriend.)

The preface is a little more honest about how the anthology shaped up. “As the stories in here show,” writes Lorinc, “dumplings—and dumpling-making—turn up at critical junctures, especially those moments when knowledge and emotion pass from one generation to the next.” The essays are, by an overwhelming majority, about the authors’ emotions around dumplings—or, more precisely, the people they eat dumplings with. I counted! The personal essay to non-personal essay ratio is 19-to-9.

That a book which was clearly meant to be a mix of food history, cultural history, and personal essay ended up being two-thirds the latter is probably more about the conventions of food writing than anything else. Even the expository essays in the anthology tend to include intimate scenes. For instance, Marie Campbell contributed an essay about the history of porcelain on the premise that “many of the most ubiquitous examples of material culture are food-related.” It opens with Campbell eating dumplings with her daughter at a restaurant which uses plastic bowls which reference traditional china. “Gnocchi Love,” Domenica Marchetti’s gnocchi inventory, starts with a vignette of her parents’ first date. Cheryl Thompson’s “What’s in a Name? The Jamaican Patty Controversy,” which chronicles the history of the dish and the Canadian government’s failed effort to regulate the name “Jamaican patty,” begins with the author’s recollections of her mother cooking Jamaican food during her childhood, even though her mother never cooked patties. The personal essay has hijacked narrative nonfiction in general, as evidenced by Jackson Arn. It has so subsumed food writing that it barely registers as a deliberate stylistic choice; it is simply the default. The chatty food blog evolved for many reasons: the demands of SEO, the desire to increase eyeball-on-ad time, the rise of the lifestyle influencer, and, of course, that readers respond positively to it because it’s enjoyable to read. It’s hard to ignore the feeling that this style of food writing has supplanted much of the food media landscape.

Some myopia is an unintended consequence of this personal essay bent in What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings. For example, many of the essays reminisce about the authors’ parents and grandparents making dumplings, and few probe the enormous amount of work that goes into assembling even a modest dumpling spread. The authors largely conceptualize it as a life-affirming labor of love, and I have no doubt that this is honest. That’s not the only perspective, though, and broader historical and cultural dives may have unearthed larger questions about, say, migration and foodways, domestic labor, and restaurant labor. Some of these themes are addressed in the book, but they are relatively sparse.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings contains specifically the personal recollections of folks who— understandably, given that they are contributing to an anthology on dumplings—really, really like dumplings. Per the blurb, the book is about the “magic” of dumplings. This betrays a presupposition underlying the anthology: that the dumpling is so universally beloved that its import is self-evident. Authors assert that dumplings are “a textural symphony” (David Buchbinder), “the exclamation point made at the end of a labor of love” (Perry King), “offerings of little bliss” (Mekhala Chaubal), “the ultimate comfort food” (Arlene Chan), “miraculous” (Nainu Duguid), or “the edible embodiment of comfort” (Julie Van Rosendaal). Readers who do not already share the contributors’ zeal for dumplings may or may not be convinced.

The writer, translator, and Full Stop editor Fiona Bell critiques the “What We Talk About . . .” title convention, which cribs from the title of Raymond Carver’s 1981 short story collection What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. She writes, “Who is this ‘we’ doing the talking about something? Unless the author defines this group—and her position within it—all she offers is a universalizing perspective.” Even in an anthology with dozens of contributors, What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings does the same. This collection, though it offers stories from a diverse range of contributors, lacks different perspectives. Most contributors view their subject with something approaching reverence.

Contributor after contributor reminds us that it is impossible to define a dumpling, but surely there would have been something worthwhile in an earnest attempt to try. Dumplings are instead, by and large, stand-ins for these contributors’ relationships with their families, friends, and selves. This makes for an engaging read, but leads What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings to fall short as a book about dumplings. The book is a showcase of the dumpling. It misses the opportunity to explore, or even interrogate, the most universal of foods.

Hallel Yadin is an archivist and writer in New York City.

This post may contain affiliate links.