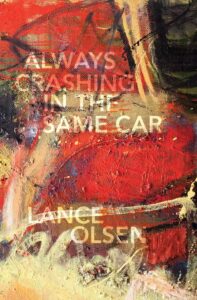

[Fiction Collective Two; 2023]

Alec Nolans sits in a Berlin apartment surrounded by boxes filled with interviews, newspaper clippings, autobiographies, and archive materials. Scribbling on index cards, he attempts to piece together a portrait of David Bowie from the splinters of information available to him. Nolans, who is also the author Lance Olsen, does not believe he will arrive at any true understanding of the English musician, who died in 2016, but he is going to do it anyway. Lance and Alec, referred to as both I and we, “envision a yearlong series of experiments in thinking, empathy and doubt.” They will produce a novel with invented scenarios and conversations, many personas and many costumes—a protean structure beyond genre or categorization. Alec only appears as a figure hard at work; Olsen is the voice standing over his shoulder, re-ordering, contemplating. Always Crashing the Same Car is, in many ways, the novel that American writer Lance Olsen was born to write.

For thirty years, as both practitioner and teacher, Olsen has been exploring the outer regions of post-genre culture, working with collage, hyper-text, poetry, and essay. In his 2012 manual on writing, Architectures of Possibility, Olsen proposes that the modern novel should function in a different space than what has come before. “Behind that proposal,” says Olsen, “lies the assumption that writers work in a post-genre culture. Here there is no longer a significant difference between prose and poetry, between fiction and non-fiction. Theory, it takes for granted, is a form of spiritual autobiography, while all writing is a kind of theorising.” Always Crashing the Same Car, with its fragmentary approach, each chapter a new mask, stays true to his word. The book doesn’t blur the lines between history and invention, fiction and nonfiction—it doesn’t recognize the existence of these lines in the first place.

A man notices a small blemish under one ear while shaving. “This man suddenly in his sixties, this man who looks fifteen years younger than he is.” He considers this mark for the briefest of moments before turning his attention to his morning coffee and cigarette. These are the final days, the routines, of David Bowie: reading, visiting doctors, spending time with wife and daughter and ever-present assistant, Coco. He is becoming somebody else, a dying man. This persona of Olsen’s, a fictitious depiction of Bowie written in the present tense, returns throughout, imagining one possibility of the end of Bowie’s life. Other chapters, each one named after a Bowie song, dress altogether differently. In “All The Young Dudes,” seemingly random bursts of fact and opinion displayed like aphorisms or cuttings from a magazine, appear like reminders to Bowie. “You receive your first instruments as presents before you are ten: a plastic saxophone, a tin guitar, a xylophone.” And later, “On Diamond Dogs, the story goes you play nearly every instrument.” Separated by asterisms, these small details—tidbits of history, quotes, facts—work in pointillist fashion, forming a larger image over time: a portrait.

For Lance Olsen, in Berlin on sabbatical, the death of Bowie speaks to the impossibility of knowing a person. “That’s why this project will be a love song, not so much to him, as to the lacunae around the thought of him.” And the book’s pleasure lies in Olsen’s awareness that he will never build an accurate version of Bowie. The title of the novel, a song which appears on the album Low, written and recorded when Bowie lived in Berlin, speaks of this inevitable, repeating failure: to be always crashing in the same car. “This is a form of happiness, these askings, these attempts at understanding what one can’t understand.” The notion of an ever changing, unplaceable Self, stems, Olsen writes, from Bakhtin’s concept of unfinalizability as outlined in Problems of Dostoyevsky’s Poetics. “Nothing conclusive has yet taken place in the world . . . everything is still in the future and will always be in the future.” Unfinalizability applies to all things—books, people, history. These things are malleable shapes, presented in different forms, glanced at through different lenses over time. As Olsen explains, “Each time we return to a text, regardless of our best efforts, the years will have regenerated it, our sublet world become reorganized around it, we will have been translated into a foreign tongue of ourselves.” This reorganizing of Bowie is at the heart of the novel, providing new languages and meaning—none definitive, none necessarily accurate. At the same time, Olsen appears to be reorganizing himself. He is getting older, confessing, “I won’t be writing many more books. Better keep an eye on the egg timer or the years will bite you.”

In one of the most striking chapters, “Diamond Dogs,” Olsen lists people and their connection to Bowie. This includes his son Duncan, formerly Zowie, “who witnessed his father fall short of maturing, repeatedly,” and Angie, first wife, mother of Zowie, and the musician’s “perennial business adviser.” In “Everybody says Hi,” Olsen imagines a journalist’s interview of Angie. Like in David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, this section elides the questions, only offering Angie’s answers as she explains how she alone was the visionary behind Bowie’s success. “I was the one who urged David to sell the outcast as a lifestyle. Break down gender borders, too. That was me.” According to Angie, David owed his entire career, every inch of success, to her. After their divorce, what did she get in return? “He airbrushed me out of his life. I lost my work, which was David Bowie, and I lost my family, which was Zowie.” This is no hagiography. Bowie’s fascist sympathies, sex addiction, drug-addled erraticism, and unreliability, do not conjure a likeable figure. “You think I’ve been too hard on Bowie at times?” asks Olsen. “Of course I have. I revere him. I therefore have the right to find him human.”

In “Warszawa,” time speeds back and forth, years collide, (“It’s 1977, yet also 2014”) history is scrambled. Chronology holds no appeal for Olsen. After all, “one can never accurately manifest history, but rather only the problematization of the very idea of pastness.” The ensemble of styles forms a patchwork of repeating patterns, techniques that, like a Bowie outfit, both clash and complement one another: ever changing facades, with no attempt to uncover a truthful essence. But, after all, Bowie’s constant reinvention, a new outfit for a new era, was never meant as a gesture of verisimilitude—it was a way of utilizing clothes to become post-fashion. By writing in a variety of costumes, Olsen, too, is becoming post-genre. In many ways, they are sharing clothes.

And, even as the versions of Bowie we encounter are fabricated, the connection between Bowie and Olsen feels authentic, as if attached by tendrils. The critic and author Adam Mars-Jones, writing in the New York Times earlier this year, suggested that authors should avoid entering their own novels to explain the works’ origins. “Postmodernism has made readers wary of any such claims of historical veracity, and in any case, stories win us over with their fruits and flowers, not with their roots.” Always Crashing in the Same Car is the perfect counter to Mars-Jones’s precious view of the novel, which doesn’t allow for any digging in the soil, or tampering with the traditional methods of storytelling. If this book is any indication, post-genre culture does indeed display its roots alongside the flowers and fruits—and is all the better for it.

Simon Lowe is a British writer. His stories have appeared in EX/Post, Breakwater Review, AMP, Akashic Books online, Ponder Review, and elsewhere. His novel, The World is at War, Again, was published June 2021 (Elsewhen Press).

This post may contain affiliate links.