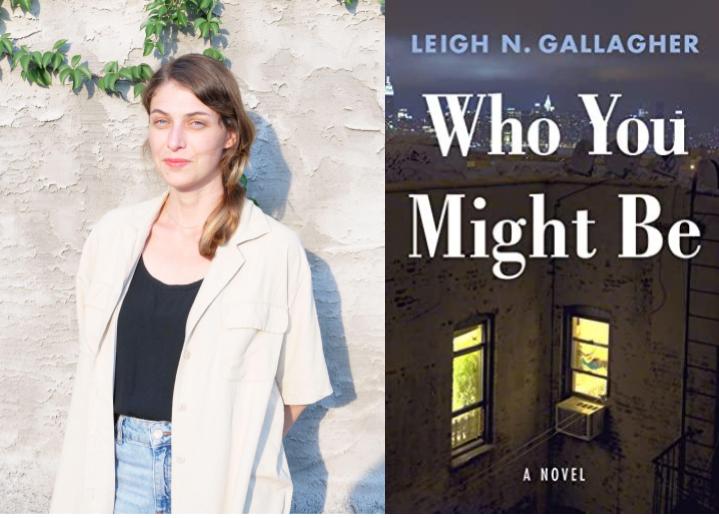

Leigh Gallagher’s debut novel, Who You Might Be, was published in 2022 by Henry Holt and released in paperback in June of 2023. Over its three parts, Who You Might Be follows the storylines of an ensemble of characters, spanning the US and two decades in time. The novel first immerses us in the teenage angst of Judy and Meghan, whose travels up the California coast to San Luis Obispo go awry when the internet friend they hoped to meet is not there. The second part introduces us to a pair of brothers, Miles and Caleb, who are unexpectedly plunged into Detroit’s graffiti-writing subculture after moving from the Bay to Michigan. The third section tracks the ways these storylines collide in New York City twenty years later.

The novel is a brilliant study of the possibilities that are opened up when writers resist the allure of the conventional narrative arc. As Leigh says in our interview, she was fascinated by the ways that “stories of different characters tangle, or explode on contact, or narrowly miss each other, but create vibrations nonetheless.” Who You Might Be records these vibrations, documenting how even events in which characters play a peripheral part can redirect and shape their lives. In representing the literary and art worlds of New York City in the third section, Leigh’s novel also grapples with the ethics of storytelling. What does it mean to own a story, when the reverberations often exceed a single person? When does making work about others become a kind of theft?

Over several emails last winter, we discussed these and other questions. It should be noted that Leigh and I are good friends, and our friendship has traversed many of the places in her novel: Detroit, Los Angeles, and New York.

Matt Polzin: One thing I find so fascinating about your novel is the way that it resists homing in on any single protagonist, giving us instead this assemblage of loosely connected characters. At one point, you write, “If Miles was Caleb’s shadow, Caleb was now Tez’s—like those cutouts you did in construction paper, folded figures all linked at the edges.” I love that image of the cutouts, and I’ve been thinking about how it also describes the linkages between characters within and across the book’s three sections. I’m curious to learn more about your approach to constructing a novel with multiple storylines. Was it something you sought to do from the very beginning, or did it come up later in the writing process?

Leigh Gallagher: I’m so glad that this is the first thing you want to talk about. Yes, the desire to tell a multi-story story was there from the beginning. At first I was writing these short stories that I sensed were of the same fictional world, but I didn’t yet know how they were connected, or what they might be saying to each other. Later, as more coherent drafts formed, some stories dropped away while others took hold, and several years in, the form of the novel—essentially as three connected novellas—solidified.

Some of my favorite texts have always been those that rove from story to story, consciousness to consciousness, and challenge the convention of both writer and reader “investing” in one central character. I think often of Linklater’s Slacker, and The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, Lisa Halliday’s Asymmetry, and Michelle de Kretser’s revelatory novel The Life to Come. What attracts me in all of these is the possibility that resonances between characters and events can take on a power and logic of their own. In the simplest sense, I think a story that’s really an amalgam of stories feels most reflective of my own position in the world. So the question became, how can one novel suggest the multitudinous histories, experiences, and ways of being of individuals? And how might the stories of different characters tangle, or explode on contact, or narrowly miss each other, but create vibrations nonetheless?

I feel compelled to add that as evocative as I find the idea of a book that’s disinterested in a central protagonist, I think it also sets up additional challenges for the writer. In the process, I found myself considering, OK, if I’m going to try to subvert one of the primary expectations a reader brings to a work of fiction, I also want to be particularly generous in other ways—specifically with characterization, setting, and plot—in hopes of earning the reader’s trust.

I love that you name both Slacker and The Life to Come. Like those works, your novel seems adamant that it doesn’t make sense to look at the self in isolation, that we learn something deeper by approaching it from those moments of encounters and resonances.

So much of your novel also seems to be about the fictions people tell themselves in crafting a sense of self, both the omissions and embellishments. In the third section, when numerous characters meet each other in New York City, we see them still struggling to produce versions of themselves that they can live with. Both Caleb and Jude, in very different ways, make sense of past experiences by repurposing other people’s stories. For instance, Jude writes short stories that remix earlier events in the novel with her own memories. I couldn’t help but wonder, were you commenting on literary fiction, its possibilities and the attendant risks, or reflecting on your own writing process?

Yes, very much so. The last few years I’ve found it nearly impossible to not write about writing. When I was an undergrad in the early 2000s, I interned briefly at McSweeney’s, when the magazine was still pretty new and had these tongue-in-cheek submission guidelines (do they still?). One of their “don’ts” was “No short stories featuring writer characters.” This left a searing impression on me. I had just started writing and was totally intoxicated by it—I felt that I was discovering something supremely strange and enlivening and psychedelic—and even more so because, as your question suggests, creating fiction doesn’t just happen on paper, it’s also how we tell ourselves to ourselves, and that narrative feels particularly potent at the formative age of eighteen. But here was a very cool magazine warning me that my discovery of writing was also cliche and boring, so much so that it was off limits as a creative topic. (I don’t want to imagine a literature in which Renee Gladman or Claire-Louise Bennett followed this annoying advice.) To add to my confusion, my workshop teachers were all about write what you know! and assigning inspirational Natalie Goldberg chapters. Without putting undue blame on either McSweeney’s or San Francisco State University, this is just to say that for a long time I struggled with a real amateur’s tension between the fear of writing boring/cliche fiction, and a loyalty to writing what I thought I knew.

Among other things, Who You Might Be provided a place to write this tension. I came out the other side accepting that what I know more than probably anything is the experience of writing—of struggling to give form to what might otherwise remain formless—and that it was absurd and even negating for me to not writing about writing, either directly, through writer-characters, or indirectly, via diary entries, verbal storytelling, graffiti writing, digital communication, and other forms of text-based sense-making that cycle through the book.

In Jude I wanted to create a writer-character whose work begins in memory and lived experience, but pursues imaginative possibilities—constructs fiction, literally—in order to concretize what’s otherwise suggested metaphorically throughout the plot. And because, yes, I felt some self-implicating need to confess the creative origins of many of the stories nested therein. Plenty of things that happen in the book are based on anecdotes and narratives collected from friends and strangers, years of overheards I’d been living with for a long time. It’s hardly different, I think, from what compels any fiction writing: You translate some real event through the filter of yourself, try to make sense of its fuzzy and mysterious elements, and it becomes your strange objective to fill in the fuzz, though there’s no essential version to compare your bootleg version against, so the task is never complete. Ultimately I’m totally thrilled by this. The challenge and the pointlessness. Maybe that’s the confession I want to make through writing writer-characters—the confession of real, self-involved pleasure in the fool’s errand of the writing process.

One character who isn’t as savvy as Jude and Caleb in reinventing herself is Bonnie, Jude’s mother. Your sketch of her is so nuanced. She’s remorseful, gregarious, and somewhat naive. She desperately wants her daughter’s forgiveness, but she’s a constant source of offense. Even as I was rooting for her, I was just as often cringing over her politics. There’s something tragic in how she simply does not seem equipped to make up for the things she’s done, which feels tied to class and her troubled relationship with an ex-partner. What motivated you to make Bonnie a focal point of the third section?

Much of this book concerns itself with millennial characters in their teens as they “come of age.” But in the process of writing, I came to realize that I don’t believe in the validity of the bildungsroman trope. That finite point of adult arrival never actually arrives; the self will always be in-process regardless of age, and the evolutions we undergo are rarely predictable or progressive. I wanted the adult characters, in Part 3, to undermine assumptions of what it means to grow up. Caleb’s “adulthood” is predicated on a lie, while Jude’s remains mostly aspirational. Bonnie, too, is a stunted character. She’s a woman for whom the bewilderment of the present era and the anxiety of where she finds herself personally—aging, in a state of economic precarity, and facing daunting realities in her relationships—intersect in ways I find both devastating and common. Her responses to this condition are survival mechanisms from all over the emotional map: She oscillates between denial and sensitivity, self-pity and admirable resilience. The traditional narrative arc depends on change, but in this section of the novel, self-transformation is the province of the still-young (Jude), or the male (Rick, Caleb). So the tragedy of Bonnie’s character is that she’s unable to change in the ways that both she, and Jude, wish she could—despite the ease with which the world she lives in changes.

In the most literal sense, her character was an opportunity for me to explore where a life can go under difficult circumstances. According to demographics, there are Bonnies all around us, right; but how do we write them post-2016? I wanted to see if I give full credence to Bonnie’s psychology and worldview, problems and all. As you point out, her politics aren’t what the reader, or other characters in the novel, might wish they were. But such is the makeup of our current social fabric. In one way, the choice to focus on her was a means of asking myself and the reader to set aside certain assumptions, to fully consider Bonnie beyond her more superficial qualifiers, and to question the criteria by which we take a person, and their struggles, seriously.

For my final question, I want to ask you about imagery. Your sentences are stuffed with beautiful, alarming, and deeply weird images. Your descriptions estrange mundane things, like the train compartment of the Coastal Quest that Meghan and Judy take to visit Cassie. You mention dandruff absorbers. You even italicize these dandruff absorbers: “Seatback veils—dandruff absorbers—wisp up, then lower, all by themselves.” I just Googled “dandruff absorbers,” and the only search results that came up were your book, which attests to your inventive use of language. How do you approach working on an image?

Thank you Matt, you’re a dream reader for caring about the origins of these fabricated dandruff absorbers! I remember them from Amtrak trips as a kid, when the threat of head lice was constant (those mortifying “lice checks” with the popsicle sticks during class and my mom’s admonishments against sharing combs or hats with my friends, which of course I did all the time), so it must’ve been my vigilance about scalp protection that made their impression last. I guess they’re actually just called “headrest covers” or something, but Meghan and Judy rename them in their adolescent way of making the world their own; a stage for their friendship, their stories. I think I approach writing images in much the same way I approach story or character; as suggestive of a bigger constellation. To hit notes that sound off other notes in the reader’s imagination.

I’m a sucker for the hyper-specific, the sensory adjective or particular noun that indicates milieu or affect; subscribing, I guess, to William Carlos Williams’s “No ideas but in things” and to Barthelme’s definition of writing as “restoring freshness to a much-handled language,” plus an instinctive, not-trending preference for the maximal, Jamesian description. It’s in this opportunity to select my own “things,” the surprising or frustrating alchemy of attempting to restore (even the tiniest bit of) freshness, and the desire to exhaust a subject by over-writing it, that I find things often get fun and weird and therapeutic. At the same time, much of the process I’m describing is refined or disappears draft by draft. But the traces that are left hopefully belie these underlayers of consciousness.

Relatedly, your question has me thinking of our conversation a few weeks ago, about the extent we fiction writers might feel troubled by the creative possibilities of ChatGPT, etc. I’m sure I’m betraying my very limited understanding of AI when I say (optimistically? naively?) that whatever our human-writer responses are to the varied outcomes of this technology, maybe one of them will be a freer embrace of language and syntax; a stranger, less literal, more capacious, or otherwise altered deployment of words, even in the service of “traditional” narrative. Maybe the coming years will see more fiction writers writing poetry. I don’t know. I hope so.

Matt Polzin is a fiction writer and PhD candidate in Literature and Creative Writing at University of California, Santa Cruz. His work has been published in the Chicago Quarterly Review, Bathhouse Journal, Mimesis Magazine, and elsewhere.

This post may contain affiliate links.