[Cloak; 2023]

How to inhabit space? How can words enable an expression of this inhabitation? Can words recreate how space is occupied? Can words describe the claustrophobia or the openness of a space? And can that lead to poetry? Would penning such a poem make one a poet or an architect?

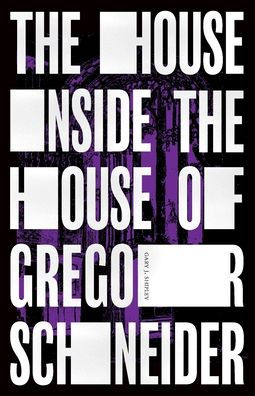

The aesthetics of space, and the politics of how one should pay attention to descriptions of space in a text, are enrichened by these questions, raised by Gary J Shipley’s textual work, The House Inside the House of Gregor Schneider. In this linguistic map of a poem—which functions as a prose poem, puzzle, and tribute to German artist Gregor Schneider, among other things—one comes face-to-face with the substance of architectural thought, the boredom and the monotony of living, and somewhat ironically, the poetry made possible by the horror of it all.

Shipley’s book and the eponymous house are based on German artist Gregor Schneider’s experimental film Die Familie Schneider (2004), a film with two channels recording his installation of two identical, neighboring houses, inhabited by identical twins occupying identical spaces, and doing identical things. The project (comprising the house and the film) is a reflection on the repetitive nature of life and living. Shipley renders the experience (of Schneider’s project) discursive through a language that speaks of repetition through doubles, triples, and quadruples, as the “I” in his narrative enters the house and shares his experience of what it is to walk through it, live in it, hate it, and reflect on life and death in it. The “I” stands for the twins, the camera, and the camera person in Schneider’s project. The three sections of the narrative begin with:

I enter the house inside the house alone.

I enter the house inside the house inside the house alone.

I enter the house inside the house inside the house inside the house alone.

Each sentence refers to something within something, something in front of something, or something below something:

I open a fridge inside a fridge (processed cheese triangles inside other cheese triangles, bottled gherkins inside bottled gherkins), rattle through two layers of bead curtain into another living room inside a living room and sit on a brown sofa containing another brown sofa.

As one reads further, one gets giddier trying to keep up with the maze. It is an impossible walk with the “I”: listening to the words in one’s head, trying to keep track of how the “I” can possibly go on, trying to visualize the map of the house and getting lost in the process. It is a house from which, to put in “I”’s words, “there is no escape.”

Roaming around the house, “I” notes, “There’s nothing here to alleviate the stultifying air of boredom and implied violence, save copies of copies of the Sun and telly guide.” It also brings “I” to reflect on what has become of their life:

I can’t avoid the avoidance of myself in here. My living of my life, like some dreadful trauma about trauma, is endlessly replayed without resolution or consolation.

It is a strange, metatextual process: Like the story drawing attention to itself in a work of metafiction, “I” and the house lay bare what it means to exist. Because there are things within things, one is forced to confront through the resulting claustrophobic disorientation whether anything can mean anything at all. It is only when spaces and things reveal themselves like this to people that one truly confronts them and engages with them deeply: “The banality of banality . . . no room outside a room for unsuspecting innocence” reveals that “the house inside the house is an architectural cover-up, an attempt to conceal the past under a veneer of normalized normality.”

The most philosophical (and perhaps unintentional) dimension of Shipley’s reconstruction of Schneider’s house—and not a gloomy one given the note of despair in the other existential dimensions that repetition unfolds in the text —is a tension between the Platonic disdain for representation of representation, idea of an idea, and copy of a copy on the one hand, and the Aristotelian counter to the Platonic idea in the form of mimesis or imitation as taking one closer to the idea. The poem is a balance between positing a distance from things that are twice removed from reality, and things that open themselves beautifully the more they are removed from reality. These metatextual objects are not fakes but agencies that tease out reflections from observers or readers by helping them get self-reflexive about objects, as well as the lives in which they are found. It is a balance because in replicating the idea within an idea, the house within our house, the number in front of a number, the wall in front of a wall, the objects don’t open themselves up as mere copies, but as manifestations of the idea itself, because the idea per se is so organic or has a deep sense of integrity. That something lets itself be replicated, ad infinitum, also brings forth the idea that the truth may be singular but its expressions are many. Or maybe not, but equally importantly: “places inside places just look the same although quite different things have happened there.”

What adds a redemptive touch to the litany-like rendition of the house in Shipley’s craft is “I’s” courage to share everything about the “monstrous” house with others:

I can stand in front of a wall in front of a wall for hours on end, looking at it. I can do that once, twice, for a whole month or even longer, and then at some point I can tell everyone about that wall.

Despite all its gloom about death, The House Inside the House of Gregor Schneider feels fascinating for its form. The repetitious rendition of the space makes it hypnotic. Pages 200–201, for instance, have the reader feel like they were staring at something in a trance: The words “in front of a wall” are spread throughout the pages and suck one into a rhythmic daze. Reading the PDF galley intensifies the experience of repetition and loop that “I” finds themselves trying to navigate. Indeed, it is this digital text—starting out as an adaptation or exploration of the larger signifier of Schneider’s house—that becomes an independent text, more faithful to Schneider’s project of communicating the angst of modern life. The text is likely to leave readers dizzy and also amazed that they do not feel the same exhaustion while living with banality, repetition, and boredom every day.

Soni Wadhwa teaches English at SRM University, Andhra Pradesh, in India. She is a regular contributor to Asian Review of Books.

This post may contain affiliate links.