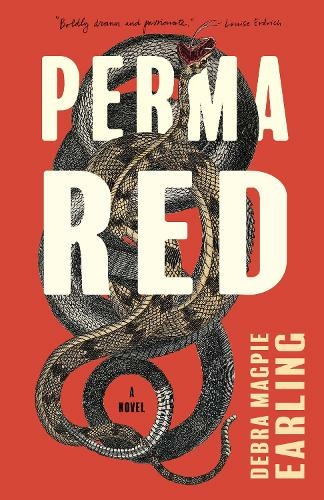

[Milkweed Editions; 2022]

Debra Magpie Earling’s novel Perma Red is set on the Flathead Indian Reservation along Montana’s Flathead River, current home to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. The novel follows Louise White Elk, a young woman trying to gain independence and agency in a system stacked against her. In the United States, Indigenous women are still disproportionately victims of domestic violence, abduction, and murder. While set in the 1940s, Earling’s engagement with the complexities of reservation violence rooted in the traumas of settler colonialism and modern capitalism make the story of Louise White Elk as resonant as it was when the novel was first published in 2002.

The novel opens with the “Old Marriage” of “Louise and Yellow Knife”: “When Louise White Elk was nine, Baptiste Yellow Knife blew a fine powder in her face and told her she would disappear.” Young Louise’s nose begins to bleed. Baptiste hands her his handkerchief. She lies on the floor to try and stop the flow. Baptiste cradles her face and whispers a story in her ear. The boarding school nuns pinch her nose and wait. When Louise’s grandmother arrives to take her home, “Baptiste smile[s] at Louise and lift[s] his bloody handkerchief up so she could see all he had taken from her.” That night Louise dreams of snakes trapped deep in the snow. This is where the saga of lust, trauma, and obsession between Louise White Elk and Baptiste Yellow Knife begins.

Years later, sixteen-year-old Louise, looking for her own agency in womanhood, finds herself caught in the orbit of three men who desire her, and whom, at times, she desires in return: Baptiste Yellow Knife, a man of the “old ways”; his cousin Charlie Kicking Woman, a tribal officer stuck between tribal and US governments; and white real estate developer Harvey Stoner, whose only connection to the Flathead Reservation is his desire for land development.

Baptiste Yellow Knife inherits the powers of “the old ways” from his mother, Dirty Swallow, a “rattlesnake woman,” who can charm a rattlesnake at will. For this reason, Baptiste holds a more ancient form of cultural power than Catholic indoctrination and settler violence. Early in the novel, Louise’s grandmother warns her to avoid Baptiste and his mother for fear that an outstanding gambling debt between the two families will endanger Louise. From the moment he blows white power into her face, Baptiste develops a psychic hold on Louise often described as love medicine. “She felt an urge to move closer to him,” Earling writes, “a strange urge she didn’t understand, the same urge she had to look close into the small mouths of dead animals.” Despite her grandmother’s advice to steer clear of Baptiste, she can’t. At times she seems motivated by curiosity and genuine interest, but at other times, she appears captivated by love medicine. Their eventual marriage seems almost inevitable.

While the love magic between Louise and Baptiste seems fated, Charlie Kicking Horse’s obsession with her is one of protection and desire. Despite having a wife and family, Charlie allows his obsession with Louise to distract him from the struggles of his daily life. Conflicted between the world of police and the world of Indigenous culture, Charlie represents a modern duality of Indigenous survival in a colonized country. “When I began as a police officer,” he recalls, “these stories [of the “old ways”] took a backseat to the small houses filled with hungry children.” Charlie is self-aware in his obsession, admitting that his pursuit of Louise interferes with his work performance. “I had failed to gather all the information I needed from Louise in order to do my job,” he confesses. “I didn’t respond to the call like an officer,” he continues, “because I’d been too busy giving Louise advice about Harvey Stoner.” Harvey Stoner is perhaps the least trustworthy and most dangerous man of all because he doesn’t have a single tribal interest a heart.

Earling writes the novel in alternating points of view, an omniscient third set against a subjective, desiring first. While Charlie Kicking Horse tells his own story, Louise’s and Baptiste’s chapters are told in an intimate third person. The use of multiple, conflicting perspectives enhances the story’s lust, obsession, and trauma. The first person narrative allows us to grasp the intensity of Charlie’s desire, while the third person voice gives breadth to Earling’s poetic prose, and particularly, her attention to the characters within the living landscape: “Louise listened to the cracks of weeds. Little licks of flame rounded the swamp grass and sizzled smoke.”

What I love about Perma Red is that it is not just a coming-of-age story, it’s the story of what it means to be caught between worlds—Indigenous North American, Colonial US American, forced Catholicism, Indigenous spiritual beliefs, all in what is most likely early post-WWII in the beautiful yet unforgiving landscape of Montana. The tension and rich storytelling follow Louise through what often feels like a fever dream as she runs towards or away from each of her suitors, often met by sex, violence, and tragedy, including the haunting drowning of her sister. As Louise’s marriage with Baptiste unravels, the novel returns to the first incantation Baptiste whispered in her ear: “You will disappear.” Louise suffers so many physical and emotional injuries, it seems she is disappearing.

Reading Perma Red, I think about Cutcha Risling Baldy’s We Are Dancing for You: Native Feminisms and the Revitalization of Women’s Coming-of-Age Ceremonies. Early in the book, Risling Baldy comments on the influence of colonial patriarchal misogyny that continues to grow and seed itself in Indigenous culture, leading to a devaluation of the feminine. This imbalance causes harassment, abuse, dismissal, disappearance, and often the death of young Indigenous women. This reality is hauntingly present throughout Perma Red, beginning with the title—a derogatory nickname given to Louise behind her back to reference the red light district.

Throughout Perma Red, it’s unclear whether Louise will survive her suitors, whose obsessions with her often result in violent harm. What haunts me about this book is not just the historic and present reality of missing and murdered Indigenous women across Turtle Island, it’s also the way readers have historically described the book and its protagonist. After the book’s first release in 2002, the Chicago Tribune wrote that Louise was a “destitute young woman.” In the same year, Publisher’s Weekly called her “restless” with a “problematic passion for irresistible bad boy Baptiste Yellow Knife.” I think it’s important to consider the way in which a review might dismiss Louise as a woman, an Indigenous woman, and an Indigenous woman coming-of-age as she carries her personal and ancestral trauma. What cultural beliefs and traumatic histories are erased or obscured when one describes Baptiste, as an “irresistible bad boy”? What are we missing when we blame Louise for making the choice to marry an abusive, obsessive man? It’s important to consider how the dismissal or flattening of characters can stem from a bias, not so different from the bias Louise experiences when she is called “Perma Red.” To read the novel this way is to miss the complicated, difficult, and lyrical story of a woman coming-of-age in the intersection of two worlds. The story of Louise White Elk helps readers see just a bit more clearly what it can mean to be Indigenous and a woman in the United States.

Amy Bobeda holds an MFA from the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics where she serves as director of the Naropa Writing Center and teaches pedagogy and processed-based arts. She’s the author of Red Memory (FlowerSong Press), What Bird Are You? (Finishing Line Press), mi sin manitos (Ethel Press), and a forthcoming project from Spuyten Duyvil. She’s on Twitter @amybobeda & @everystoryisamenstrualstory on Instagram.

This post may contain affiliate links.