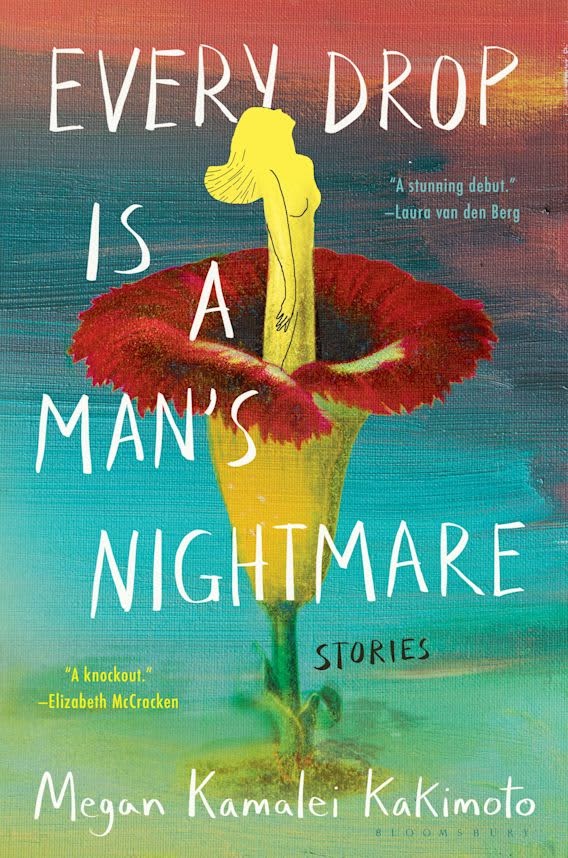

When I sat down with Every Drop is a Man’s Nightmare, I was intrigued by the unique structure of the first story written as a list of Hawaiian superstitions. The rest of the story collection felt like a journey into this mythical world of Hawaiian characters and landscapes. I was fascinated by the universal themes the book addressed and the nuances of Hawaiian culture and folklore. The uniqueness of the voice made it a compelling read, and I was curious about the decision behind the varying narrative voices. As an Indian writer, I was keen to understand the author’s concerns about a target audience and appeal to a larger audience while writing about her culture and traditions.

Swetha: Every Drop is a Man’s Nightmare is an intriguing collection of stories about Hawaiian mythology, folklore, and superstitions. How and when did the idea to pen this down transpire?

Megan Kamalei Kakimoto: I started working on the first story, “Temporary Dwellers,” in 2015. It was an important story for me as it opened up the entire collection, which was surprising as this story is not heavily grounded in superstitions. It was also a challenging story for me as a writer, as I had essentially been putting off writing stories that were set in Honolulu for a long time. It boiled down to the fear of wanting to represent my culture responsibly. With this story, I wanted to explore nuances of desire, wounds of colonization endured by Hawaiian people, and growing up as a little girl in Honolulu. I didn’t write these stories thinking of them being in a collection. I was trying to find myself as a writer. The idea of bringing in superstitions and mythology crept up in my writing. It took a while, but it eventually paved the way for a collection. In a way, “Temporary Dwellers” felt like a permission-granting story.

It’s interesting how you mention “Temporary Dwellers” was the first story you wrote, and it falls in the middle of the collection. How did you decide on the order of the stories in the final version of your book?

Arranging the stories in a particular order was a big challenge, mainly since it caters to the reader’s experience. At least it does for me. Since my book is not a linked collection, the way the same place or character connects other collections, I was anxious about how the ordering would end up. I worked closely with my agent, Iwalani Kim, and my editor at Bloomsbury. I wanted to create a list of superstitions to map how to read the rest of the collection. The first story is a coming-of-age story, and I ended it with two women at the end of their lives. With the rest, I looked at how the stories were speaking to one another and how the arrangement can create tension and elicit emotions in the reader.

One thing I always wonder when writing a short story is how a story should be told. I noticed you have used first-person narrative in some stories and a close third in others. How did you end up making these narrative choices?

I don’t know if it’s something I think about intentionally. A lot of that might be an intuitive thing that happens when I write. I spend a decent amount of time with the characters’ voices in my head. I thought about these women and their lives when I went for walks. I got an intuitive feel about what is suitable for that particular character, allowing me to use that point of view. The last story in the collection was one of the most gut-driven stories I have ever written. It came so naturally. That doesn’t happen to me a lot. I write quick and messy first drafts and need help. That story came together effortlessly as I knew those two women’s characters well.

It was fascinating to read the list of superstitions. I realized how similar they were to some of the Indian superstitions. How did the idea of writing in a list format come to you?

The story emerged from a writing prompt I received in my first year of my MFA in 2020. It required us to write something in a list format. I was excited about the freedom this kind of prompt offers a writer. I went with the flow, and this list of superstitions came out on the page. I liked the idea of this list being an anchor for the collection as a warning list. Interestingly, what follows suit is the story of a young girl who defies these superstitions. It was an enjoyable way to bring readers into the collection.

Was there any specific superstition that stuck with you since childhood? Anything that influenced your writing?

The one that stayed with me because of the frequency with which my parents reminded me of it was the superstition not to drive over Pali Highway with pork. This inspired my story “Every Drop is a Man’s Nightmare.” My grandparents lived on the same side where Sadie’s stepfamily lived in the story. We would visit them usually over weekends. Every time we would drive there, my parents would bring this up, almost as though they were talking about this superstition for the first time. The history behind that superstition is the Hawaiian legend tale between Pele and Kamapuaʻa—who was half man and half pig. One of the popular versions of this story was that they were lovers, then became ex-lovers, and they owned each side of the island. Bringing a pig over the valley meant we brought Kamapuaʻa to Pele’s territory. This was imbibed in my mind as a kid. So, I started thinking about that superstition from the perspective of a little girl at a delicate and vital point in her life. I also love writing about menstruation and the female body. I just wanted to get all these ideas on the page.

Another superstition ingrained into me was the one about not whistling at night, which is common in many indigenous cultures. It points to the history of Night Marchers in Hawaiian culture. They are Hawaiian warriors who have the power to protect our most secret sites, and so whistling at night is like calling them. I don’t have a specific memory of childhood I can point to regarding this superstition. But it was an important one, nevertheless.

I was curious how old you were when you were told about these superstitions.

I know I was at least six or seven. My parents never weaponized them. There was always this storytelling bend to their explanations. It was more like what their ancestors or they believed in, and they were merely passing it on to me.

Folklore is always fascinating to listen to during childhood. Did your beliefs ever change as you grew older? Did you find yourself questioning the logic behind these superstitions as an adult?

I don’t think it did when I was an adolescent. However, I thought about these superstitions a lot more in my twenties. A lot of people should have taken these superstitions more seriously. I discovered these superstitions in our Hawaiian stories and how they play a more significant role in our mythology. This brought a little more profound understanding of these superstitions, and I came to a place of respect for them.

According to Indian superstition, we do not beat up a lizard as it’s considered the Goddess of Wealth. Sometimes, we eventually kill a lizard and live with that guilt. Has any such experience happened to you where you have gone against a superstitious belief?

It’s interesting how you mention the lizard. The lizard, or the Mo’o, is considered our ancestral protector and takes the form of an animal. I was always told to leave the Mo’o alone. In my twenties, I remember accidentally closing the door, and there was a lizard in the hinge. It fell on the floor and made a sound. I didn’t know what to do initially and didn’t touch its body for a long time. My worries began to spiral, and it was unsettling. I realize it’s easy to fall into the web of superstition that disturbs you.

You earlier mentioned this fear of writing stories based on superstitions. How did you manage to overcome this fear?

Growing up, I learned that many of our superstitions were shared with Chinese and other Asian cultures. Many people who came to work in our Hawaiian plantations brought their set of superstitions. I took a lot of comfort in realizing that. There is beauty in the camaraderie of conversing with people from other cultures with similar beliefs. I felt liberated from that fear and chose to present these fiction stories authentically.

Did you ever worry about your target audience or how the white audience would receive stories deeply rooted in Hawaiian culture, myths, and superstitions?

Yes. A lot of people ask me who my target audience is. I tried not to be deeply bothered about my audience during the writing process. I have yet to think about what one particular audience is interested in reading. There is a lot of pressure writing from marginalized experience to cater to a wide readership and a traditionally white Western audience. But there can also be pressure from your community sometimes to present cultural stories responsibly. All those combined pressures make it difficult for me to write. While I know the ideal reader for my book would be an Indigenous Hawaiian woman, I also want these stories to be read widely. There needs to be more Hawaiian representation in contemporary literature, and I would like to see more Indigenous Hawaiian works celebrated. I have been excited to see what has been published in fiction and nonfiction. The Night Parade by Jami Nakamura Lin beautifully captures Japanese culture. Personal stories like that being championed in publishing are exciting. As a reader, that’s what I crave. I want more people to bring their cultural or ancestral tales into contemporary ones.

Do you think Indigenous authors should write keeping a specific audience in mind or where their heart leads them?

They should write where their heart leads them. I am inspired by writers who write their own stories without worrying how they might be received or criticized by the White audience. That’s fearless, and writing work you can stand by is essential. There is no guarantee about how well it will be received. If you are writing something you are proud of, that’s my goal.

Would books like yours and The Night Parade make agents, publishers, and the Western audience more receptive to authors who want to write on a similar premise?

I hope so. There are so many more stories and voices we need to hear. Even thinking about my community of Indigenous Hawaiian writers, I’m one voice among so many. I always want my book to be a way to open doors to more voices and stories to come through. Stories like these and ours should be read. They deserve as much space as works by western authors.

Writing a book so deep-rooted to your culture can be life-altering and a learning experience. Has writing this collection changed you as a person?

In so many ways. As mentioned earlier, I was initially afraid to write and share some of these stories. The reception of this book has been heartwarming. Readers have been able to connect to its universal themes. Every time I hear that, it makes my fear diminish to a large extent. Writing this book has also helped me clarify my voice on the page, which has evolved and changed.

What authors or books inspire/influence your writing?

I love this. It is Paradise by Kristiana Kahakauwila. It was the first story collection I ever read by an Indigenous Hawaiian author. She had this fearless approach to writing her experience of what it was like to be Hawaiian. This book granted permission for me. I love Lorrie Moore’s collection of stories. Her stories are the ones I always return to. Joy Williams is another author I admire. For fantastical stories, I love Kelly Link, Karen Russell, and Kiana Davenport—a native Hawaiian author whose novels have influenced me.

Are you working on any projects at the moment?

I am working on a novel at the moment. It’s under contract with Bloomsbury. It revolves around a menstrual house where the women would rest and be with other women. The novel examines this experience in a contemporary context.

Swetha Amit is an Indian author based in California and an MFA graduate from the University of San Francisco. Her works across genres appear in Atticus Review, Had, Flash Fiction Magazine, Maudlin House, and Oyez Review. She has received three Pushcart and Best of the Net nominations. When she’s not writing, Swetha loves to play pickleball and participate in running and triathlon events.

This post may contain affiliate links.