[Litmus Press; 2022]

Elisabeth Houston’s debut book of poetry Standard American English explores, only to disintegrate and put on display, the exploitation and commodification of art, labor, identity, and the body. This book is an object to be read, interpreted, and reinterpreted. It is interested in dissecting what it means to exist under the authority of language—amalgamating identity, the body, and relationships into a spectacle. baby, Houston’s performance role, and a speaker of this book, wryly asks, “are we at a labor & feminist conference?!? / is this a critical ethnic studies symposium?!? [ ] / . . . or are we on the catwalk at commes des garçons!?!?!?”

This book is of, and works through, academia, yet it is against it, criticizing the violence inflicted upon the body by an invisible authority of success. It attempts to break down, and eliminate the idea of institutions, offering up the multitudes of roles one is required to perform to succeed, and be an accomplished academic and/or artist. An example lies in baby, whose multifaceted persona skips and does not stick to narrative, whose name is never capitalized. Perhaps like baby, the language I am interested in deconstructing is just as multidimensional and protean. “There is no single speaker in this book,” Houston says in an interview with Ashaki M. Jackson.

I wanted to reveal the contradictions within language, voice, and narrative. How you read the book quite literally depends on where you are inside the space of the text. . . . What is revealed in each voice is how language is corrupted and deformed by power.

The lack of a singular speaker allows for multiple selves to trickle in, displaying a holistic, fallible individual. The distinction between baby’s personas is nonexistent; these voices engage in the daily performances one must execute in different contexts, relinquishing any semblance of a pure or integrated self.

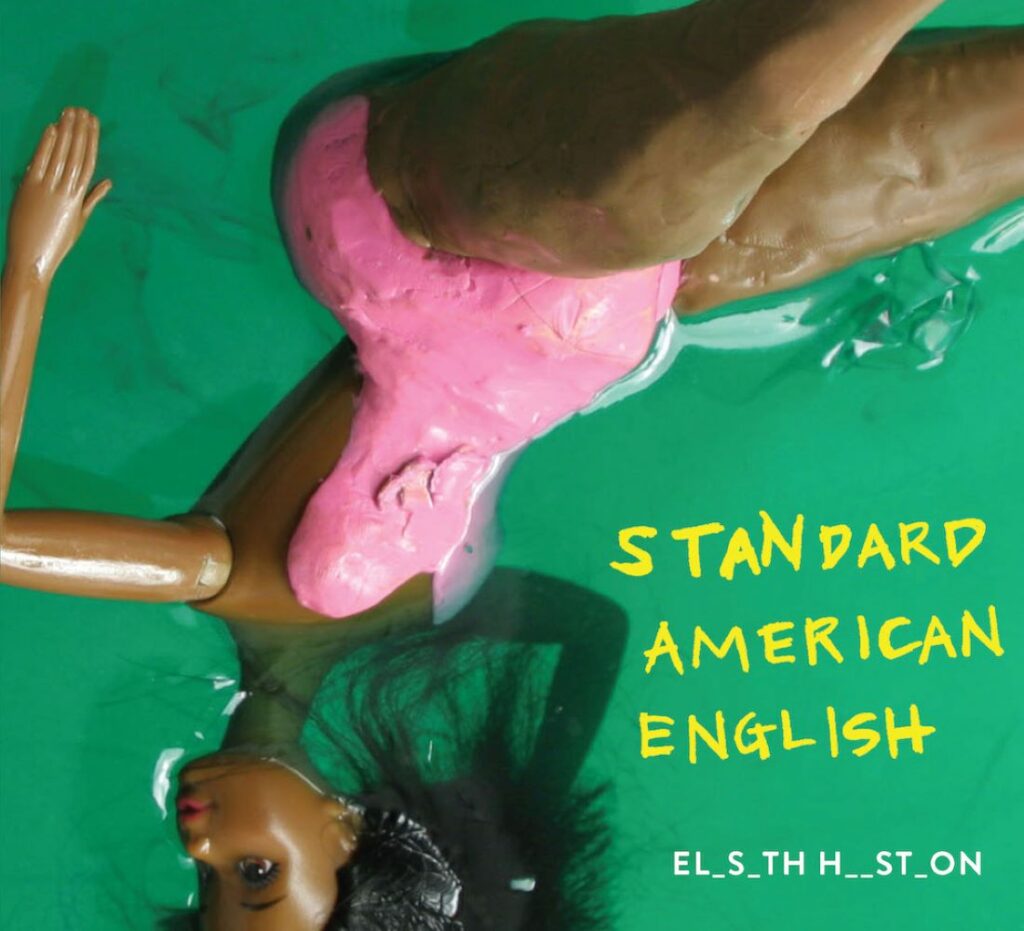

The name of the author on the cover of this book, Elisabeth Houston, lives within, and through openings. Houston’s name is not “full,” instead there are gaps where letters ought to go. Gaps unequal to the name and letters needed complete her name: “EL_S_TH H_ _ ST_ON.” In this sense, Houston refutes language, or at the very least refuses to be authored by it.

“shhhh” opens the first page. It is the title of the first out of the four sections, indicating a quieting down, the susurration of sound, suggesting music and the manifestation of language. The words become an action, turning bodies into embodiment; the action is shaped by language, the idea shaped in and by the body. This is expressed through baby, “[who], of course, feared that she’d be rejected from art institutions & art people & artsy art; sure. she’d sold out, she’d rejected her true self, so she might become a bigger self. she’d hoped to become . . . a piece of art, itself.” In this book, language is not a two-dimensional entity—words on a page, words of a mouth—but a theory, system, like air one breathes, shaping and performing and putrefying. As Houston writes, “[baby] could point at terms & gather language . . . but she never looked within, she never looked within language, / she never looked within herself.”

Often the line of text is stretched out. It takes up the page, breaking down language into sound, into sounds incomprehensible on the flatness of a folio: “& — chhhhhllllllmmmppffff — clears his throat,” baby hears when listening to johnny t. walker, and “blahhhhh blahhhhhh / yes! yes! we’re shimmering! blahhhhhh blaaaaahhhhh,” when she is listening to mother. These sounds become musical—or reminiscent of song—while holding a beat, or a note. When Houston writes, “the poem fails not because it lacks language,[ ] but because it lacks depth,” she might be referring to the superimposition of language onto the self, the body, and the contours of the superficial form. In this way, Houston’s poems defy poetry with its horizontal, orderly dullness of words when only discerned on a page. Houston creates an opening in the act and experience of reading beyond the codex, morphing it into music and the sound of the body. Utilizing footnotes, as though an analysis written in the Chicago Manual of Style, or perhaps a music score, they become further instructions, a deeper cut into the story. What becomes visible may not be beautiful nor digestible, playing to the interiority of the subject so heavily wrought by the influence of the marketplace. The footnote becomes an extension of self, the extension of the story. There is more to the center, the body, and the self than the initially glanced facade. Following the line, “oh so proudly! imma . . . rrrrrrrrraddddiccccallllll,” Houston elaborates upon baby’s internal clash with power and self:

baby was constantly broke and constantly angry—and she thought she had to be angry in order to be rrrrraaddical. the fight wasn’t worth it, but she wasn’t quite ready to give up. she found too much comfort in the idea that she was standing on the right side of history, she found too much comfort in the illusions of moral superiority, and so she didn’t realize that she might possibly be wrong. she might be right about capitalism, but she might be wrong about herself and her position within the whole enterprise, her position within the machine. baby thought she stood outside it, when she stood at its very center. she thought by raging against the system, she thought she was somehow removed from it. it was no wonder she pounded away and she found herself tired. she was pounding on air.

This air is infiltrated with language, assailed by the spores of speech. In the same interview with Ashaki M. Jackson, Houston remarks, “Books come to us for a reason, and part of what brought me to writing this work was an urgent need to create a new language. I needed to construct a new vocabulary out of this simple alphabet; I needed to believe that it might be possible for me to enter into language and participate in it.” Standard American English, a widely proliferated idea, a classification of English taught in schools in the United States—when split down the seams etymologically—reveals an insidious domination and manipulation of its subject. Houston does not break down this phrase, yet as a participant of language, I am interested in the cacophony of meaning embedded in its tissue:

Standard:

“From shortened form of Old French estandart ‘military standard, banner.’” To be static, to be of place, to stand up for one’s nation, as in to be patriotic, to be a monument. Houston plays with the idea of a monument, differentiating between poetic divinity and “A Celebrated Public Figure” authorial status: “& baby didn’t want to be a bronze statue / which stood in a courtyard of A Particular Ivy League University / only to get pissed on by drunk frat kids walking by . . . / why would she want to be that kind of writer?”

American:

America is the widely used term for the United States, disregarding the fact that the Americas extend from the North of present-day Canada down to Patagonia (the southern tip of Argentina and Chile). And America, as we might know, is the name given to the land mass by Spanish colonizers, after Amerigo Vespucci, an Italian “explorer.” There are alternatives to the naming of the Americas, such as the Amerrisque mountain range in Nicaragua or Richard Amerike, an English merchant. For Houston, America stands in for a dream, an idealized lifestyle: “father & mother & baby live at the end of a cul-de-sac in the great town of maplewood, land of the uuuunited states. they love maplewood, they love the house they live inside: the green grass, the white picket fence, the big front porch . . .”

English:

“‘The people of England; the speech of England,’ noun use of Old English adjective Englisc (contrasted to Denisc, Frencisce, etc.), ‘of or pertaining to the Angles,’ from Engle (plural) ‘the Angles,’ the name of one of the Germanic groups that overran the island 5c.” The Angles were white and war-fueled, sometimes referred to as barbarians by the Romans. Middle English continued to be influenced by French, as in The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer. English, becoming a globalized language, picked up phrases, vocabulary, and intonations from Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, Farsi, Latin, and other languages. A cosmopolitan language, English does not discriminate who to utilize for profit: “the rulz of money demanded baby exploit the bodies / of those she employed then enjoyed. / she didn’t value them, she didn’t love them. / it was a simple transaction; cruelty was only the natural order of things— / the rulz of money said so, said so plainly—plainly in Standard American English.”

What is language when broken down, but a series of bricks and constrained objects taking new shape or form? Yet, language is a bearer of violence, distributing intonations so callously that it can alter one’s interiority and overall schema. Such transformations occur for baby “[who] discovered herself only through the eyes of others.” Elisabeth Houston’s continuous fracture of language, unearthing its guileful and brutalizing essence, questions the idea of knowing, how we know, and how language is utilized.

Olga Mikolaivna works in the (intersectional/textual) liminal space of photography, word, translation, and installation. She is an MFA candidate in creative writing at UCSD. Her work can be found with Cleveland Review of Books, Tilted House, TQR, and elsewhere.

This post may contain affiliate links.