Jane Wong is the author of two acclaimed poetry collections, Overpour (Action Books, 2016) and How to Not Be Afraid of Everything (Alice James Books, 2021), and a forthcoming memoir, Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City (Tin House, May 2023). She holds an MFA in Poetry from the University of Iowa and a PhD in Asian American Literature from the University of Washington and is currently an Associate Professor at Western Washington University. Jane’s work is centered around her Chinese American identity and is often transcendental. Her poems reach out across space and time and shake the reader to pay attention.

I was lucky to get my hands on an early copy of Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City and found myself enamored with Jane’s prose. As an immigrant memoirist myself, I felt like Jane was writing directly to me. She tackles traumatic subject matter with unapologetic grace, like an absent gambling addicted father, her upbringing as a low-income immigrant restaurant baby, illegal Chinatown dentistry, a bout with stealing, a string of failed romances, emotional and physical abuse by a former partner she calls The Bad One, and the racism and bigotry she has endured as a contemporary Chinese American woman and girl. Unlike her poetry, her memoir does not rely heavily on metaphor—although there are plenty of animal similes—but is more direct, often breaking the fourth wall and addressing the reader. In the chapter, “The Object of Love,” Jane quotes a friend’s relationship advice. “You are not hard to love,” her friend Michelle insists. Jane replies with: “Current and future me still needs the reminder.” And then addresses the reader: “Maybe you do, too.” Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City is like the fertilizer Jane’s mom (also known in the memoir as momwong.com) cultivates: regenerative, redemptive, and full of hope.

Jane Wong is a generous conversationalist. Below is a condensed transcript of our March 14 Zoom call, shortly after a busy weekend at AWP in Seattle, where Jane lives.

Diana Ruzova: You’re a brilliant poet with two acclaimed poetry collections. What drew you to the memoir form? Did you always know you were going to write a memoir? What surprised you most while writing Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City?

Jane Wong: When reading the memoir, it’s very clear that I’m most certainly a poet. A lot of people don’t know this about me, but I began as a fiction writer. When I was in college, I only took fiction classes. But I struggled with plot. That was my biggest thing. Nothing really happened. I remember when I took a poetry class for the first time, I was like, “Oh, you don’t really have to have this go anywhere in terms of the narrative.” But something goes somewhere in terms of that emotional weight or whatever the philosophical question that you’re raising. So, I fell in love with poetry because it’s so playful.

Coming to the memoir is kind of like a weird return to writing prose. I had almost forgotten how much I love sentences. I was working on this dissertation for a chunk of time, which is all sentences. So, I was like “Oh, I’ve actually been doing a lot of prose!” I think I’ve always had this kind of lyrical obsession. I can go on lyrical tangents which I delight in, but sometimes they have to be reined in.

This memoir began as essays. I didn’t really plan on writing a memoir. My editor was like, “Tin House would really love this as a memoir,” and I was like, “I don’t know how to write a memoir.” It was a total journey in terms of figuring out what is memoir exactly, and how in many ways my poetry is also memoir.

In terms of the standalone essays, I was trying to figure out how the essays could be woven together. How to create a braid (like wongmom.com). I’m so glad that I did it. It was definitely one of the hardest things I’ve done creatively because it required so much of me. I think that as a poet I can just kind of dangle a metaphor and walk away and have the reader do the work. In memoir, I have to do the work. I had to reflect and not run away as much. It was a huge learning experience for me as a writer, but also for me as a person. Even literally coming to the page knowing I had to have a word count of 300 plus pages is very different from one page [of poetry].

I’m curious about organization. Your memoir is nonlinear, which I love! What about the structure were you most drawn to?

I just love nonlinearity. I don’t know if I can even write in a linear style. My PhD was in Asian American literature, so I teach Asian American lit. Many of the books that I teach are nonlinear, like Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictee, The Best We Can Do by Thi Bui, and Mira Jacob’s Good Talk. The actual experience of migration and the actual experience of thinking through what identity means here in the US, the process of immigration, and the impacts over generations, none of that is linear. It’s just not possible to say, “Begin here,” right? I think in memoir readers are expecting a certain degree of linearity: “This is where you begin. This is how you grow. And this is where you ended up.” In many ways I think that a lot of Asian American memoirs are pretty transgressive. That said, I wanted to push it even further. I was kind of obsessed with time. When we think about time, we think a lot about the past and present and future or what is timely. I think wongmom.com is an interesting character that I made-up . . .

I would like to hear more about the origins of wongmom.com. In the memoir, wongmom.com introduces new topics and appears occasionally as short section breaks with distinct black borders.

She’s not real per se. She lives on the Internet. I wanted to take a risk with the memoir. I wanted to imagine what it would be like if my mom was a big Internet name or Tik Tok star or something, so I gave her a website. I really think that a lot of it is playful. A play on ancient Chinese wisdom, like it’s not the I Ching, it’s wongmom.com. Some of my book is quite heavy and traumatic at times, so I needed her personally to track my emotional trajectory as I was working on this book. I hope people like her. I love her.

I’m making the website, so it’s really exciting. It’s going to be an old school nod to the early days of the Internet. I really owe a lot to my friend Brandon who pretty much brought up this idea [wongmon.com] almost like a joke, but I really ran with it. I think writing nonfiction—as I’ve told a lot of my students and other writers—you really want to write about the big things that happened in your life, but I like to start from something super tiny or something seemingly inconsequential. I think wongmom.com is a tiny moment from a walk with Brandon that became this huge thing. I’m always looking for the little, tiny ants in my mind that actually do a lot of the heavy lifting.

Your memoir is about so many things: about growing up as a child of immigrants, a restaurant baby, about the struggles immigrant parents face and the generational trauma inherited by first generation children, about predatory casinos and how they specifically pray on Chinese American immigrants, about an absent gambling addicted father, trouble with romance and an abusive romantic partner, and most importantly what it means to be a Chinese American woman today. But at the heart of your memoir is a love story, between the narrator and her mother. Was the love story baked into the narrative from the start or was it something you uncovered in the process of writing?

I think it is a love song or love note or a giant number-one-biggest-fan foam finger to my mom. It was definitely baked in from the start. It began with my first book, Overpour, and moved into my second book, How to Not Be Afraid of Everything. My obsession with my mother is kind of funny because I do feel like I can’t stop writing about her. I can’t stop thinking about her. I really do feel as if I’m attached to her. I’m always discovering things about her. She’s the original storyteller. The original poet. The original fashion icon. When she walks into a room, everyone’s like, “Who is this?” and even I feel that way as her daughter. I said it during a few panels at AWP, that I feel like the off-brand cereal version of my mother. Like I’m not her at all but I’m trying so hard to be her in some weird way.

She’s gone through so much in her life sometimes without me even knowing. She never shared any details about the intimate violence between her and my father until I told her about The Bad One. She’s always been obsessed with this idea of regeneration or fertilizer. She’s very powerful. There’s some sort of power within her that draws people to her. She’s delighted by little tiny things and I have to remind myself that it’s part of being a poet; to walk down the street and say “Wow! The grass is this particular color today.” My mom is like that. I write for her. She’s a total extrovert. She pushes back against so many stereotypes that Asian American women are tiger moms. My mom literally didn’t even want me to take upper-level AP classes because she didn’t want me to be too stressed. She’s just not that stereotype.

She gave me permission [to write about her], but we had a hard time with the chapter “Root Canal Street.” She’s a very beautiful woman and having to admit that she had bad teeth was like a big thing we had to talk about. She ultimately agreed because it was really about us and not necessarily about her teeth. I had a very honest conversation with her about the book and that was really meaningful. The book is absolutely a total love song for my mom.

It sounds like she’s so supportive of your poetry and your writing, which battles the stereotype of immigrant parents wanting us to be pharmacists or something.

That’s one of the biggest things people always assume for some reason! And I have to be like, “No, my mom wasn’t like that at all. She was never ever strict with me.” I think about this all the time. I feel very privileged to be able to write poetry and to be able to write these books. When my students call me professor or doctor, it always freaks me out because I’m just Jane. If my mom had the opportunity to make art—she couldn’t with the financial demands of putting dinner on the table—I wonder what she would have made. I feel really privileged I get to do this, almost like on her behalf. One of the ways that she did express herself was certainly through her style and her fashion and her cooking. It’s very clear she’s an artist.

Let’s talk about teeth. It feels like nearly every immigrant family has a complicated relationship with the bones in their mouth. Like this essay in Guernica from January 2023 by Soviet immigrant writer Tali Perch. How did you approach this subject? You mentioned that it was challenging: elaborate a little bit more on that.

I love how you phrased it in terms of the bones within your body. This book is very very very tied to class and what it means to grow up in poverty, low income, working class, all throughout the different generations of the family and the ways in which that impacts your body.

It also feels like teeth are one of the first things that people see right away. They are just so on display. They tell a story.

I have a lot of my own questions I need to work through in terms of scarcity myself and it certainly comes from growing up as child of immigrants. I know when someone is truly wealthy when they have great teeth. They were able to get braces. Growing up without healthcare and growing up without dental care, I didn’t even really know that people had insurance.

I also grew up as part of a family business. My parents managed an apartment building, and we lived there rent free. We didn’t own the property. It felt like I was always on display. No privacy. Did you feel this way as a restaurant baby? Do you think this prepared you for the writing life?

When people come from a family business, it’s just totally different. Like you said, you’re on display, you’re public. It’s strange to think about what that means for a kid. I was always there [at the restaurant]. When I go home to Jersey as a full grown almost forty-year-old adult, people will stop us on the street and say, “You’ve gotten so big.” Personally, as a child, I had a delightful time. The customers became my family. I would borrow books from the Public Library, and I would always get so sad about returning them, so one of the customers would come by and place his order and give me a book. I started my collection via him. I would write stories and draw pictures on the back of the menus. I mostly hung out with the customers and didn’t really hang out with kids my age. My friends were adults that just so happened to be customers. Of course, there were some totally racist customers, too. They would tell my mom that they couldn’t understand what she was saying, and I would have to step in, but the vast majority of the customers were super kind. But I guess I didn’t have any privacy.

It seems like it did shape you as a writer, in a way, because it shaped your imagination.

For sure. Totally! One hundred percent! There are so many sounds and smells. An absolute cornucopia of metaphor and sensory description. You could listen to conversations that customers were having. It’s just such a rich space. Every day is going to be different.

You mentioned how important libraries were to you as kid. Librarians were also my free babysitters. My immigrant mom would drop me off at the Public Library while she ran errands. This was so formative, not just for my literary life, but for my independence. In your memoir you mentioned rewriting endings in library books and sending messages through slips of paper to other girls like you. I’m curious how these solo library visits shaped you as both a poet and a woman?

I love that! Oh my gosh, librarians do so much, especially for children. They definitely shaped me. When I was growing up in the ‘80s, there weren’t a lot of folks that represented me, especially in kids’ books. I would get frustrated. I was an incredibly shy child. I didn’t even say a word in class until the fifth grade. That’s why they put me in ESL.

I was also put in ESL for a little while because my parents didn’t speak English, but I knew I didn’t need it.

Wow! We have so much in common.

At the library, I was reading these books and thinking, “I could do that.” And maybe I could do it even better because that character doesn’t make any sense. Or how come I don’t see myself? I was silenced for a very long time. I think that so much of that silence was because they thought I didn’t have a lot going on, but I had so much to say. I’ve never really written poetry about my experiences of domestic violence. This memoir is going to be the first time it comes out. I think about my younger self in that library and how I was willing to take a risk by slipping those pieces of paper in library books. I knew I could get in trouble, that someone would read them and maybe hate them. I think that in a way there is still this kind of riskiness within me.

In the chapter titled “A Jane by Any Other Name,” you write about the origin of your American and Chinese names. How your mother boldly asked a customer in her restaurant to name you and your brother. You also dive into research on famous women who share your last name, two of which are actresses. The ‘20s-era actress Anna May Wong and indie darling Faye Wong made famous by director Wong Kar-wai, who I also love. You talk about Anna May Wong’s struggles with type casting and the lack of Asian representation in American media. I’m curious if you watched the Oscars recently. How do you feel about Everything Everywhere All at Once taking home so many awards? Particularly Malaysian actress Michelle Yeoh, the first Asian woman to win best actress.

I don’t even know how to watch the Oscars, so I didn’t literally watch it. However, of course I saw the breaking news on social media. This is the movie I’ve been waiting for. Michelle Yeoh playing a character who’s working class; it is just a stunning movie. I almost don’t even have words. When I went to see it for the first time, I was teaching an Asian American literature class. It was a big class. I was planning to go see the movie with my friends, but when I told my class, they insisted we go see the movie together, so we went to the movie theater. Some students brought their classmates and roommates who were also Asian American. It was so sweet. It covered all these themes we talked about in class. It was like a dream movie.

I’m so thrilled obviously that it scooped up so many incredible awards at the Oscars, but I keep thinking to myself that the Oscars is a large organization. . . Who was actually giving us this stamp of approval? And why now? These actors deserved recognition way before this, right? I was teaching during the earliest stages of the pandemic, during all the Asian American violence. I think a lot of my students were quite stunned. But this violence has been here this whole time.

In your memoir, you write about the pandemic and the recent uptake in Asian hate. The very recent present. I’m curious if you wanted to speak a little bit more about that.

It feels safer to write about things that have some distance in terms of time. I really really really wanted to write up-to-the-minute. There’s no demarcation for me. I remember after I wrote the chapter on the rise in Asian hate, I read an article later about the so-called “duck sauce killer,” and I was like, “What is happening?!” Every single time I would write something, a new thing would happen in the news. Grief upon grief upon grief, in real time.

I felt like if I didn’t go up to the actual minute it would be a disservice to myself. I’m always trying to bring it in as close to the minute as possible and that was a risk. People say, “Don’t write about the pandemic.” I hate it when people talk about the timelessness of writing. I’m like, “Absolutely not, what does that even mean?” We live in time, yes, even if it’s messy time. How do I not write about the pandemic?

Immigrants are susceptible to get-rich-quick schemes. My own family was on the verge of investing in pawn shop businesses and timeshare pyramid schemes. You touch on your father’s gambling addiction and the predatory casinos that bus Chinese immigrants to the slot machines. I’m curious how this predatory behavior affected your family? Also, in the beginning of your memoir, it felt like your father was going to play a larger role. Was there a conscious decision to not include him and his story as much?

When I was growing up my mother and I didn’t see the larger systemic predatory behavior particularly targeting immigrant communities. But it’s part of a larger system preying on folks who are vulnerable and in precarious positions financially, wanting the “American dream.” The desire for something big to happen in their lives that can change the entire direction for generations. I think that was my father. His personal gambling sessions were very different from him going to the casino and getting the free hotel rooms, the casinos trying to woo him to come back, always always.

The restaurant fell apart, not necessarily due to the smaller gambling sessions that were happening between friends at mahjong tables, but it was due to the casinos. My father was so addicted to gambling that he almost lost sight of the fact that he had a family. He would just disappear.

My mom is the center of my life. It wasn’t a decision to not include my dad as much. It’s just more of a reality. My father’s not in my life. I have no idea what his life has ended up being. I think about him. I know he’s in Jersey and he’s getting older and I worry about him all the time. It’s really hard to grapple with my tenderness and forgiveness towards my father. I don’t know anything about this man besides when I did know him. I don’t know who he has become. My mother became this larger-than-life entity after he left. It’s honestly a tragic story for so many families. It’s not uncommon. The weird thing about this book is that sometimes it feels like such a unique story, but it really isn’t.

I’m curious about the title and how it came about.

The title comes from a Bruce Springsteen song. I can’t come from Jersey and not be a fan of The Boss. The song has a sense of something that could be fixed. Like somehow, we can go back in time and meet—my father and I—in Atlantic City and have some sort of a reconciliation. I don’t know. I think about that a lot. Atlantic City itself is an incredibly storied place. I like to think about cities that are difficult socioeconomically, like the casinos, but not in their heyday. I’m obsessed with places like that.

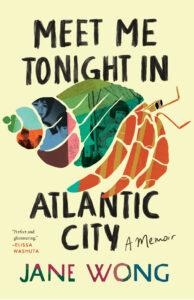

I don’t know how I feel about the word resilience exactly, because it does suggest some sort of bouncing back. The cover looks like someone wrote it in sharpie. There’s a playfulness, but it’s also pretty sad, too. Bruce Springsteen is a storyteller. That’s what I love about his songs. There’s always a story in them. People always misread a lot of Bruce Springsteen songs. For example, “Born in the USA.” People think it’s an anthem, but it’s actually a critical song.

Yes! My boyfriend has a tattoo that says, “Born in the USA.” I didn’t know much about Bruce Springsteen until recently and I was like, “Oh my God what does that mean? Are you patriotic?” and he was like, “No, listen to the song.”

Exactly. That’s what I love about The Boss. He’s a celebrity and so well-known, but he’s also a poet and a storyteller. I really admire him. Hopefully one day I’ll get to meet him.

That would be amazing!

Let’s talk about shame. It’s a prevailing topic in all immigrant literature. Is it possible to tell an immigrant story without including shame?

Oh my gosh, that is such a phenomenal question! It’s such a hard one. I’ll be honest. I feel like I knew I had to write about it, so there’s that one wongmom.com section where I ask her if she’s proud of me. I get so embarrassed by asking that question. Like I tried to take it back and wongmom.com caught that one.

Pride and shame are so tied together in many ways. The pressure to be a good “immigrant child” and the generational aspirations of what we’re supposed to do. There’s so much culturally, too. Like the gendered expectations of what I’m supposed to be doing right now, AKA getting married. That is what I keep hearing from my family on my mom’s side, but not my mom. I’ll make that clear.

I can’t avoid talking about it [shame]. I still remember my uncle on my dad’s side saying, “You’re the one. You’re going to be the first one to go to college.” That’s a lot of pressure on one person.

I’m trying to find out what the opposite of shame is. The dictionary says grace, empathy, honor, esteem, respect. I think that’s really powerful and it does it feels very redemptive.

You break the fourth wall and use a lot of direct address throughout. You’re not afraid to tell the reader, “Hey, look this up, pay attention.”

Yes, I definitely wanted to do that.

I don’t think I’ve recently read a book that had so much direct address in it.

It’s coming from a poetry background.

I read a lot of nonfiction because that’s what I write myself and I don’t see it often. What are you reading right now?

There are way too many books that I am reading. The last book I taught was Chen Chen’s, Your Emergency Contact Has Experienced an Emergency and it’s just phenomenal. Speaking of shame, there’s a lot in there. There’s one poem called Winter, that Chen refers to affectionately as the “winter poop poem.” I love that poem.

Diana Ruzova is a Soviet-born writer based in Los Angeles. Her work can be found in the Los Angeles Times, New York Magazine’s The Cut, Oprah Daily, Peach Magazine and elsewhere. She holds an MFA in Literature and Creative Nonfiction from the Bennington Writing Seminars. Diana is in the process of completing an essay collection manuscript about growing up in Los Angeles and the contemporary immigrant experience. You can find more of Diana’s work at dianaruzova.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.