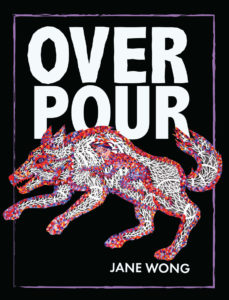

Jane Wong’s debut poetry collection Overpour is a book of blood: blood, the real livid coursing liquid; blood, the symbol of lineage; and blood, the thing whose spilling demands atonement. As an early instigator and key supporter of Seattle’s beloved Margin Shift collective — a poetry group that leans avant-garde, centers poets of marginalized communities, and throws big sprawling readings — Wong is a significant presence in the Seattle poetry community. Overpour introduces a bigger audience to her poetic voice: one potent with elemental magic, but heavy too with a sense of guilt and obligation.

The central line of Overpour is on the first page: “for years I lived this way: with words // That had to do with carrion.” In Wong’s poems, this “carrion” language of fleshliness, rot, and teeming natural vitality connects us to our embodiment and our inescapable ties to family ancestry. The poem “Blood” begins with deadpan parental wisdom — “My mother told me not to drink pig’s blood / Unless I desire health” — and describes an intimate bond in urgent, clinging terms. “I took shelter in stems and seed / I held your hand to make a root / To stay intact, we must keep everything in / No blood must be lost or stolen.” Where the pig’s blood is another creature’s life that we absorb into our own, this “lost or stolen” blood is that of a family line, a “blood tie.” In another poem, the dead body symbolizes an ancestral guilt that Wong’s speaker cannot escape:

Some cells split despite death. When they opened

up the farmer, they found a grass clot in his lungs.

I come from a farming family. Which is to say,

I have killed plenty of things: spiders, ants, crabs –

leg by leg.

In Wong’s poems, the speaker’s family connects her to history as well as to culpability. Family is everywhere in Overpour, which is dedicated “in awe” to the poet’s mother, and which includes five poems written in her mother’s voice. These five poems, each named for the age of her mother in the year they are spoken, shiver with a vivid tension. Here, for instance, is the middle of “Twenty-Five”:

A peeled orange falls

from the kitchen counter,

a sweeter planet. Laughter fillsa honeycomb some distance

away. I give you a lie as coldas a mirror in winter,

warm in fractalsof snow. No, I never did

say love.

There is little warmth in these portrayals of Wong’s mother, but there is a magical power. Sometimes it’s a power the mother possesses, as in “Forty-Three”: “I open the refrigerator // and scoop out the cheeks / of a fish. I call the fish // my husband.” Other times it’s a recognition of the metonymic significance of a natural world that is anything but a neutral background, as later in the same poem: “There is ozone / in the sky, gathering // the cruel words we say / to each other.”

This intensity and potency the poems ascribe to the mother prefigure the power Wong’s own speakers take on elsewhere in Overpour. These speakers animate, name, spy on, tend, and kill innumerable creatures — rabbit, cat, deer, chicken, raccoon, crab, goose, fish and more — throughout in the book. In the long sequence “No Need for the Moon to Shine in It,” the speaker’s consciousness creates an entire reality, which then rebels with a lifeforce of its own:

I stretch my wings across a rooftop. I am a line

of laundry drying, drawn in and folded in

haste . . . .

A blush sweeps across my face like the sun in a smoke-

filled sky. False: trees are being set on fire.

Plenty of poets — Ronald Johnson, Alice Notley, CAConrad — conceive of their poems as magical, world-creating processes, but in doing so they tend to stress the absoluteness of their agency. (As one of Notley’s speakers puts it, “I am the being / who uses words the way you use the senses to handle matter.”) In their poems, the speakers do, and create, what they want. Wong’s speakers are possessed of a similar transforming power, but the physical realities around them push back, or bind them in ways they can’t escape. In the passage above, it’s the burning trees, not the speaker’s blushing face, that sweeps the sky, just as, in “Forty-Three,” the ozone stands for an interiority that the speaker cannot conceal.

“In my defense,” Wong’s speaker says elsewhere, “I have no limits,” but this lack of limits doesn’t mean absolute freedom. Instead, it means that the speaker can have contact with every point of this material and bodily world that might at any time invoke her guilt or demand her care. The sun’s living light reveals things she’d rather not see: “The sun wrestles wildly about me, // throwing light in unbearable places” (61). And in “Familiar Stranger,” her magic calls her to a responsibility she couldn’t have anticipated: “I watered the plants / and they turned to plastic. / To take care of that / which we can not eat.” The plants, like dolls, will never live or grow, but they still depend on her. In “No Need for the Moon to Shine in It,” there is, in fact, no place where the speaker is not needed:

Under a full moaning moon, I changed into a better

self: over-empathetic. I saved every deer

tangled in every fence. I took hooves to the face.

I won awards and gave awards away to terrible people so

they can feel something.

The material world in Wong’s poems is living, resistant, and insatiable, resisting and attaching itself to the speaker in turn, so that the speaker’s magical acts don’t feel repetitive as Overpour goes on. (When you don’t know how your subject will respond, your magic becomes riskier — and more compelling.)

Wong’s book is full of images that take on a totemic significance in their recurrence — poem after poem mentions meat and eyes, smoke and sunlight — but it is ultimately the speaker’s own family who is at the center of Overpour. The poem “Blood” ends:

A bone drops to the floor

Ants gather in corners, my family gathers their faces

This funeral of plenty

Sings dirges in the marrow

This living hand, now warm and capable

My blood thick with stars

The dropped bone makes literal the feeling of funereal, bone-deep sadness, while giving the “plenty” around which the family gathers a suggestion of scavengers around abundant carrion. In “Encyclopedia, Vol.,” the speaker cautions us:

To love a rock, one must carry it on their back.

For years, my mother caught moths in our

ceiling lamps, the wings grazing her cheek.

Sometimes, she stretches to touch

my neck. One tap and I am simply

halved

Like the previous passage’s “bone,” the “rock” here takes on a suggestion by proximity — the reader can’t help but compare its beloved burden to that of family. And here, the mother’s magical potency overpowers the speaker herself: this light, shattering touch is a reminder that magic runs both ways.

There isn’t a page of Overpour without arresting imagery and a suggestion of forceful, generative life. The book begins to feel fatiguing over its eighty-two pages only because Wong, like many other poets of her generation, prefers a steady surreal declarative tone (suggesting James Tate or Heather Christle) to other registers of emotional speech or ecstatic song. The book states more often than it speaks or sings, meaning that lines like “a pot boils over and there is soup in my shoes” or “Upstairs, you sleep / with deadbolt eyes” begin to feel samey as the book goes on. The most tonally lively Overpour gets is in its moments of grim, low-temperature humor, as in “Guts”: “Sunshine spills / on the oil slick // of last night’s dinner. / My face shines / in the slick, subtly / sublime”.

But Wong’s book is assembled with care. It balances its vivid short lyrics with long sequences that sometimes suggest ceremony, sometimes memoir; and it saves its absolute best poem for last. In “Thaw,” the speaker rises above the material world of bone, blood, carrion, and culpability, and achieves her longed-for transubstantiation:

I had half an ice arm

I waved at the sun for warmth and connection

This melting chandelier of mine

A fever grew from my ankles up

A planet fell out of my mouth

My organs bloomed, parachutes in the night

With this magical change comes something unexpected in this book of verbal wizardry: speechlessness. “My verbs were all in disagreement . . . / My prized imperatives, my root words: gone.” Though Overpour suggests that we are bound to our blood — our family, our flesh — “Thaw” achieves a bodiless freedom that, the speaker believes, is worth celebrating: the final line of the book is “Long live the day.”

Jay Aquinas Thompson is poet and critic with recent work in Fog Machine, Sprung Formal, The Stockholm Review of Literature, and Berfrois. He lives in Seattle with his family, where he teaches creative writing to incarcerated women.

This post may contain affiliate links.