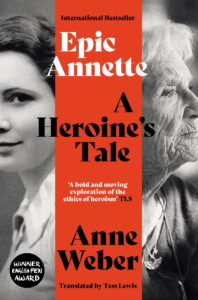

[The Indigo Press; 2022]

Tr. from German by Tess Lewis

In recent years, several novels have reconsidered both the Homeric epic and Greek mythology through a gendered lens. Written in free verse, Anne Weber’s Epic Annette engages with classical forms to chronicle the extraordinary life of Annette (aka Anne) Beaumanoir, a French neurophysiologist who was once a member of the Resistance. In its invocation of the female epic, Epic Annette feels close to “The Anniad” section of Gwendolyn Brooks’s poetry collection Annie Allen (1950), which uses the epic form to recount a Black woman’s heroic survival through racial discrimination and poverty. But who was Annette Beaumanoir, and how does her life fit the title of epic heroine?

Her feats seem incomprehensible from a young age. Born in Brittany in 1923, she served in the Resistance while a young medical student. A militant communist, she never received the national accolades of her French contemporaries in the Resistance. Instead, she was charged with treason for siding with the FLN (National Liberation Front) during the Algerian War. She escaped house arrest and initially traveled to Tunisia but later developed a renowned medical career in Geneva. In recounting the hefty price Beaumanoir paid for supporting communism and decolonization, Weber uses the epic form to juxtapose grand history and banal routine, illuminating the struggles of a woman trying to define her own agency in the midst of major social and political movements. The connection between personal identity and epic sweep is apparent in the novel’s transformative use of dramatic irony, as well as in a brief consideration of its treatment of exile.

Though frequently taught in the context of Shakespearean tragedy, dramatic irony—a literary device that allows the reader valuable knowledge that the characters do not have—has a long history in the epic form. Paradoxically, it lends suspense to the Homeric canon, as when the gods discuss Hector’s death in advance in The Iliad or Odysseus returns to Ithaca in disguise in The Odyssey. In Epic Annette, the significance of dramatic irony is decidedly poignant. A gentle but knowing narrator reveals how this passionate young woman is thwarted at every turn—often by the male intellectuals and leaders she idolizes. Rather than gods atop Mount Olympus, the engine of dramatic irony may well be the voice of bitter experience. The epic begins when Annette is elderly. “Today/At the age of ninety-five, she comes/Into the world on this blank page.” While assisting Jewish families to safety and couriering packages for the Resistance, she recognizes the value of anonymity. “She must be silent as the tiny fish she is/In the great machinery of the movement/Without acquaintances or friends.” Yet her fervent belief in communism and anti-fascism derives from her reading of André Malraux’s novel Man’s Fate (1927). “She is very taken with/Chen, one of the characters . . . Chen is driven by the idea of sacrifice, even if/Said sacrifice is a complete failure.” The narrator offers a more jaundiced take on Malraux, noting how he “acquir[ed] a dubious reputation.” Once contrasted with Annette’s idealism, these issues are all too quickly dismissed. “Regardless, his reputation isn’t our concern/Annette’s enthusiasm is.”

But by hinting at a wise cynicism that would be anathema to a young Annette, this moment sets the tone for her long collision course with disillusionment. When she attempts to join a Resistance guerilla brigade toward the end of the war, they denounce her as “too puny.” Helpfully, the narrator fills us in once again. “What she does not know . . . and this surely/Would have fanned her rage, is that the brigade/She ardently wants to join will be led by Colonel Berger, a pseudonym hiding none other than Lieutenant Colonel André Malraux.” Even as her heroic feats earn her place in the epic canon, she cannot escape the constraints of patriarchal prejudice—a fact made painfully apparent by what she does not know of her own heroes.

Annette’s misplaced faith in great men and political ideals continues after the war concludes. However, the novel’s treatment of dramatic irony grows more nuanced, elucidating what she may not realize about herself as well as the external forces shaping her fate. Why does she continue to feel this urgent need for a great cause? Despite defying the odds to become a doctor and an active communist, her postwar life becomes surprisingly pedestrian. Reflecting on her postwar life as a wife, mother, and professional, the novel captures a moment of uncertainty about her next move. Depicting how she “joins a French group/Providing assistance to the FLN,” the Algerian nationalist political party leading decolonization efforts, the narrator posits a significant digression. “Let’s not get ahead of ourselves and lose all suspense/And speaking of suspense, would it be fair to say that/It’s also a spur for Annette . . . The way France/Governs Algeria horrifies her . . . But are there other reasons?” There are the pillars of her current successful life: “children, husband, work.” A far cry from her partisan lover who died during the war, her husband “cheats on her/From time to time.” It is hard to be sure of her motives. “She is thirty-five/Everything else is mere hypothesis.” This instance reveals the limits of dramatic irony. While we as readers may survey Annette’s life from an elevated perch of hindsight she does not possess, the full complexity of her choices eludes us and her.

Still, dramatic irony continues to play a vital role in revealing the stakes of her decisions. Its presence within the novel shifts from uncovering patriarchal discrimination that limits Annette to recounting the grimmest aspects of her homeland and the movement she supports. When she couriers suitcases full of cash for the FLN, Annette is unaware that “these millions are deposited in Switzerland/In the Arab Commercial Bank founded and directed by/The Nazi bene-factor . . . François Genoud.” Nestled in the midst of Annette’s growing devotion to the FLN, this fact is a shot across the bow, a warning that her sacrifices will backfire.

Those sacrifices accumulate. Arrested for treason when chauffeuring an FLN member, she is thrown in prison for months and denounced in the French press. Finally released to house arrest, she flees family and home for an FLN stronghold in Tunis. Despite suffering, she is caught again in a momentous historical occasion, with Ahmed Ben Bella replacing André Malraux in her heroic estimation. Ben Bella, eventually the first president of Algeria, earns her respect. The narrator’s perspective is decidedly more knowing. “He was a soldier, a corporal/An arms dealer, a gunrunner and a gangster . . . And if ever had been a simple, modest man/It’s unlikely he remained one.” This second narrative warning is but a lead-in to Annette’s unfortunate realization long after his government is quickly overthrown. In this epic tale, dramatic irony reveals a diverse litany of historical facts but retains its tragic implications. Annette risked her life for a country that imprisoned and ridiculed her, only to repeat the pattern and lose her family in the process.

Epic Annette’s treatment of exile helps to draw conclusions about Annette’s unfortunate forays into historic events. When Annette flees to North Africa, she is in good company in the epic tradition. After all, the pain of exile has haunted the form since Odysseus longed for Ithaca and Dante Alighieri lamented the bitter taste of others’ bread. But Annette’s exile is figurative as well as literal—and begins when she is still in France. While in prison, she realizes that she is an outsider among her comrades. An exile from her own cause, she learns the cost of interjecting herself into an anti-colonial revolution, of linking “Algerian independence” with “her independence as a woman.” Family may hover at the margins of ancient epic stanzas, but Annette’s struggle adheres to the well-worn feminist mantra that “the personal is political.” Her urge to sacrifice all on the altar of a grand cause is hardly a total loss, as she establishes an illustrious medical career in Geneva. In a text that narrows the gulf between the prosaic and the extraordinary, form echoes content in portraying Annette’s simultaneous accomplishments and isolation. Punctuated throughout with dramatic line breaks and even designated moments of silence for the fallen, this epic poem basks in its own artifice. Author Anne Weber describes meeting Annette over dinner, transforming her dish of “spaghetti in squid ink sauce” into a moment of literary creation. “The squid begins to secrete its black ink . . . What remains/Is a black cloud, and in this cloud’s fine, black/Lines Annette comes to life.” Equating a Homeric invocation of the muse with a dinner entrée might seem an odd choice. However, it fits with the emphasis on dramatic irony, exile, and other hints of alienation. It evokes the humble, banal circumstances that defined much of Annette’s life, even if she deserved epic acknowledgement. This novel embraces the grandiosity of the epic form to pay tribute to an overlooked figure. But it never loses sight of its protagonist’s blind spots or the narrowmindedness that limited recognition of her achievements.

Despite her remarkable circumstances, Annette’s plight feels oddly resonant in an era championing flexibility and work-life balance. Her later life in France is not the triumphal return of an epic hero. Instead, she lives “short, bent and alone” in a village that reminds her of her Resistance days. The price of admission for living her ideals is so high that it renders her a permanent exile in isolation, destroying any illusion of “having it all” in the hectic mix of family life and professional achievement. Anne Weber compares Annette’s life story to French-Algerian philosopher Albert Camus’s essay, The Myth of Sisyphus. “The struggle itself toward the summit is enough/To fill a man’s heart.” By chronicling Annette’s heroism—with a wise eye on the prejudices and cruelties that stymied her—Weber evokes both epic heroine and feminist Sisyphus, a woman determined to change the world in a world that refused to make room for her.

Emily Hershman received a PhD in English at the University of Notre Dame. Her writing has appeared in the James Joyce Quarterly and elsewhere.

This post may contain affiliate links.