This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

On Goop, one can buy an egg-shaped, jade-honed object with which to “harness the power of energy work, crystal healing, and a Kegel-like physical practice” for $66; a lambskin leather braided whip “made for experimentation with kink” for $295; and, the item to which I am most drawn, a “pretty bullet-shaped pendant” vibrator necklace, cast in stainless steel and “finished in twenty-four-karat gold” for $149. The latter bears the furthest resemblance to conventional sex toy forms, and reveals the brand’s dubious ethos as a means to “start hard conversations . . . [to] go first so you don’t have to.” The pendant’s thin shaft and polished exterior references more the jewelry one might expect to see in a boutique in gentrified LA or Brooklyn—the model, clad in a body-conforming ribbed mock-neck sweater, looks ready to go for a $8 cappuccino at a cafe where she can sit in a chair reminiscent of an Alvar Aalto stool, the gold bathed in light pouring from the lofted windows, delighting in the promise of a liberated self—contained, magically, in the glimmering device hanging from her cashmere-encased neck.

“Advocating” for a sex- and kink-positivity by consuming one’s way into self-actualization is how contemporary professional-managerial class (PMC) feminists believe they practice politics, and thereby how they practice self-determination, as Kasumi Borczyk has argued, citing Catherine Liu:“[p]urchasing vibrators, anal beads and artisanal lube become acts of resistance.” But, as Liu writes in Virtue Hoarders, the material ends are in fact a “smug sense of sub-cultural superiority” that congratulates itself for casting, literally in gold, virtuous purchase power as a transformative act. Thus politics is supplanted by a prescribed ritual—say, passing a jade egg around at a dinner party in order to impart each person’s “charge” into its smoothed surface, to thereby, um, better enable its world-changing powers once inserted into its custodian’s vagina (or whatever orifice accommodating and suitable for its size). One’s individuated psycho-sexual enlightenment, shaped by virtuous marketing, becomes a lens through which collectivities, and hence the potential for a politics, are imagined, legible, and evaluated through a relation between things rather than people.

Borczyk and Liu call our attention to the myriad aesthetic forms that pander to egos weakened by capitalism’s engineering of daily life. In today’s mainstream literary scenes, where novels seem readymade by corporate literary publishers to cater to a readership mesmerized by its own guilt, politics looks like consuming as many zeitgeisty novels as one can in a year. Books featured on theNew York Times or Obama’s annual end-of-year lists seem to have been written with their film and prestige TV futures in mind, the two forms resembling each other so much one might play a “treatment or novel synopsis?” drinking game. The results are performatively satisfying but ultimately, as Liu has it, “pointless forms of pseudo-politics and hypervigilance.” In Stephen Mitchelmore’s assessment, the literary analogs for Goop’s instrumentalized pleasure technologies become “ideal for a form in search of a certain kind of power or a mirror, mirror on the wall.” That reflection empowers a readership whose values are repeated ad infinitum: By having raised its own awareness, by having made their psyches more acutely aware, readers reassure themselves that a good life might still be possible, as long as one consumes the right media, the right kind of content, whose political efficacy is measured by how “accurately” a work “tackles current affairs in its subject matter.” The more accurate it is, the more committed we will be to our politics, and the more our consuming becomes political. The more acutely identical the literary content is to its referents, the logic goes, the more politically efficacious the commodity is, with little regard for the structures that enable the representation of the horror it ostensibly critiques. This is how Squid Game becomes lauded as a searing indictment of neoliberal capitalism because you watched it.

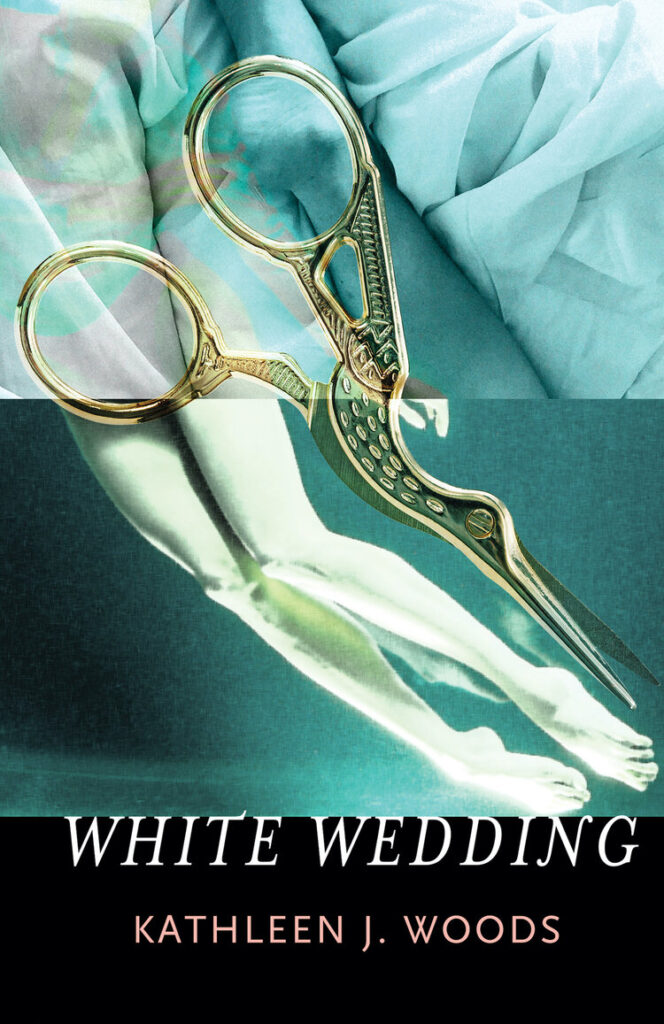

Commitment to a certain politics or ideology is not the question here. I’m not advocating for an art so esoteric that it abstracts itself into asociality. I want to instead point to the style of social engagement that contemporary storytelling, and fiction in particular, practices today. The interventions described above are doomed, for, according to Theodor Adorno, they forget that a “wrong life cannot be lived rightly,” that the social forces that widen class inequality and prop up a ruling class, cannot be endured nor overcome with the temporary balms of the most inclusive novel, the most feminist film. Within the trash fire that is much of contemporary life for a majority of the population, it seems crucial to ask: What kind of art could enable us to imagine an alternative to purchasing power–politics? What kind of art can move us beyond the commandment to “do our part” by buying a golden vibrator, compostable freezer bags, or spreading the word about the latest Netflix show? Kathleen J. Woods’s debut book of fiction, White Wedding (FC2), engages this question through the very form which the PMC has tried to optimize for its own virtue, substituting consumption for politics in what is known as “ethical” or “fair-trade” pornography, a niche market that seeks to correct the ills of mainstream pornography by, according to Dr. David Ley in an article published on Goop’s website, paying performers a “fair wage for their work, [and treating them] with dignity and respect.” Ley goes on to analogize fair-trade pornography to fair-trade coffee, writing, “when I buy coffee knowing that the farmers weren’t slaves, I enjoy it without guilt or shame.” But White Wedding does not wear its political commitments on its sleeve, flagging the reader to notice its self-congratulatory, sex-positive virtue like Goop’s golden vibrator does. Though the novel’s main character is a sex worker of sorts, she does not seem to represent the figure of the content creator in today’s supposedly “ethical” sex trade. Indeed, Woods eschews many of the received pronunciations that we see on those literary “best-of” lists—a pacy plot, introspective protagonists, and plenty of somber, “serious prose”—in an effort to revise the mode of representation itself. In these times when “authentic experiences” are just one purchase away, White Wedding calls into question our very claims to reality, to the good life, to even a glimpse of some imagined other-than not bound by the psychic straits in which the waking world holds us.

The book’s eight chapters, totaling only 119 pages, alternate between two different locations at two different points on the same timeline, temporal and physical locations eventually overlapping at the novel’s midpoint. The premise is simple: A stranger, our protagonist (identified only as “The woman”), crashes a wedding held at a well-heeled family’s house at the bottom of a mountain. She arrives certainly not dressed for the occasion. The opening scene finds her at the sink in the family’s house, “scrubb[ing] her wrists with a soap rose. Blood and cum swirled the sink as the bridal march rang from the backyard.” The book soon answers necessary plot questions, such as how the woman arrived or why Charlotte, the bride’s stepsister, just so happened to be driving by her, but these details are clearly besides the point. The set-up is as arbitrary and contrived as that of a B-movie or “smut” film (more on that shortly); the point is that the woman is here, at the wedding, and strikingly out of place. The story commences where it does to highlight the contrast between the artificially pure environment of the wedding and the protagonist’s unkempt appearance. And it is this contrast itself which suggests the plot: Hijinks will ensue, and how they do.

At first sight, this conceit has the trappings of a conventional porno: An extravagantly, inappropriately attired stranger arrives with one goal: to fuck. The book and its protagonist work their way through the party guests and staff as the narrative moves chapter by chapter between the present timeline and an earlier one set at “the mansion on the mountain,” a BDSM club where the protagonist was once employed. In the first chapter, it’s the caterer who falls into the woman’s hands (or her tongue as it were), “her tendons seizing as the woman tongued up her rib cage, [folding] back the cups of her bra.” The second chapter rewinds the tape, returning us to the mansion, where the woman drags a straight razor “over [a girl’s] labia, nicking against the stubble’s grain, scraping outward in, toward her finger and the fragile tissue it covered. Her cunt flushed hot.” In the third chapter, we’re back at the wedding, and the woman’s found herself with Charlotte again, sharing a story about how an otherwise routine night at the bar near the mansion turns into a threesome with a musician and the bartender: “My fingers pried between her thick thighs, the thin tights and sweat there.” You get the idea. The episodic structure evokes the feature-length pornographies of old, daring us to close its cover. The book seems to know what we’re here for.

Readers may pause here, and the book’s first sleight of hand is to inspire this moment of self-interrogation. Did we come here for such a story? What, even, is the story? Who is this caterer to our protagonist? To ask such questions is to betray a desire for a cohesive, linear plot. Scenes, we are told, shouldn’t just move us forward through time; they should move characters’ identities through it too, testing—developing—them along the way. But in White Wedding, we’re not reading it for the plot. Or if we are, it’s only in the way anyone watching Basic Instinct for the nth time would claim they are watching it “for the plot.” The book’s aims are more primordial, its tools transparent. Contrivance here is not a flaw but rather a convenient way to move us from one kinky scene to the next—from a room inside of the mansion to the various escapades with the wedding guests. While the flashback chapters do explain how the woman gets from the club to the wedding, seemingly deferent to a novelistic sense of understanding who the protagonist is, we never know why she’s at the mansion in the first place or who her various partners are to her. We never even learn so much as her name, and we cannot look to the narrator for such information. At the BDSM mansion, and at the wedding, the narrator’s function is effaced, limited to witnessing the protagonist seduce a multitude of characters. The most rope we’re given is when the protagonist’s extended fantasies—her favorite method of seduction—takes the narrative reins. As she reels the wedding guests in with kinky scenario after kinky scenario, it becomes clear what her purpose is: She’s here to get them off.

Charlotte and the protagonist’s fortuitous first encounter is a good example. The protagonist hitches a ride, and teases and flirts with Charlotte, who can’t help but moan about her stepsister’s wedding. She lets slip that the bride is already pregnant, implying that the wedding’s appeals to purity are rote and aesthetic. “The woman tutted. ‘Snitching on your sister. . . . When you fuck, does she tattle on you?’” Charlotte protests, but the protagonist persists. The dialogue seems right out of a smut script: “‘If you’re planning to murder me, get it over with,’” Charlotte says. The book frequently leaves us wondering about its characters’ motivations, and here the character seems to be at a loss herself. As if picking up on Charlotte’s (and the reader’s) doubt, the protagonist tells her, “‘You don’t want to know why you picked me up. And you’re good at this—you’ve practiced shutting down. So, let’s look away, a bit further. I’ll talk, and when I’m finished, you’ll tell me what’s true.’” The woman then takes over the narrator’s role, launching into an extended fantasy that stars Charlotte and her stepsister as hypothetical schoolgirls. In the woman’s telling, the stepsister goads her younger sibling into inserting a capped pen into her vagina. The details and pace are almost clinical, were it not for the obvious pleasure the protagonist enjoys in rendering the actions in wide-eyed, explicit detail as the student removes the pen: “‘Something slick and clear coated the smooth plastic. . . . [D]ripping film, bloodless, clear.’” It’s clear that the story makes Charlotte uncomfortable, but she doesn’t pull over. She keeps driving until she reaches a parking lot, where she lets her strange passenger off, perhaps believing this is the last time she’ll see her. If only the trail to the wedding weren’t so clearly traced by her tires, a trail the woman can easily travel on foot.

The language in the woman’s dialogue above is consistent with the narrative voice across the book: no euphemism, clinical or otherwise, to dull or disguise. Woods’s sentences are cumulative, pressing, and relentless in their attention to the aroused body, whether they are filtered through the narrator or, as above, when the protagonist takes control. The book’s aesthetic is one of fascinated yet detached observation; it reports more than it interprets or describes. It is wholly uninterested in, perhaps even annoyed by, the kind of attention one achieves with the close-third or first-person of many a mainstream novel.

In this way, White Wedding is clearly indebted to Pauline Réage’s classic erotic novel, The Story of O, which follows the titular character’s quest to prove her devotion to her lover, Rene, through an escalating series of sadomasochistic acts, from bondage to double penetration, all without second-guessing her master. With its direct and explicit style, Réage’s text is one of several that informed Susan Sontag’s essay “The Pornographic Imagination,” which examined how the book’s point-of-view and style transformed fiction into a physical experience rather than a psychological one. Sontag writes that pornographic literature seeks to inhabit the “extreme forms of consciousness that transcend social personality [and] psychological individuality.” We witness and watch—not inhabit, identify, nor empathize—with the narrator’s relationship to its characters. Sontag’s point is less about objectifying content for a reader’s consumption, which would appeal to a consciousness bound in a “psychological individuality,” than foregrounding the materiality of the language itself. Scenes are opportunities for experiments in explicit representation with the sole goal of arousal; their craft tests the limits of pornographic representation: “Blood and cum swirled the sink.” “She lifted her tongue to the salt.”

White Wedding’s narrator avoids interpreting and evaluating its characters explicitly, and that decision renders the narrator a more prominent character than the unnamed protagonist. Many of us have been raised on more conventional narrative strategies that train us to identify psychologically with a narrator as if it were a person, and when we are bereft of the signs of “social personality [and] psychological individuality” on which such identification typically rests, we are forcibly more aligned with the narrator’s unfiltered desire to watch than with the psychic or social changes any one character, narrator or otherwise, endures. The drama we’re invested in is how long the narrator-voyeur can persist in its looking, rather than that of a particular character’s evolution. This is consumption for consumption’s sake, for pleasure, not instrumentalized towards some grander ideal. Woods’s apparent allergy to conventional perspective enables a moral critique distinct from ego-pandering forms found in the hyper-vigilant, absolutely-of-the-moment topical narratives we see in fiction today. By making us watch how the narrator watches, the book argues that barriers to self-determination are not overcome by an even more refined psychic map—the tools and techniques of self-mastery—but by doing away with the thinking self altogether.

At the moment the unnamed protagonist objectifies her interlocutors, so too does the narrator the protagonist, and so too the reader, whose experience of the book points to the text’s aesthetic argument. We have refined our psyches so much we couldn’t feel pleasure if we tried, which is why we almost cringe and squirm at the visceral representations of activities that we might otherwise practice in other venues. Woods bears this out at one of the more memorable wedding scenes, as the father of the bride makes the following slurred pronouncement: “‘My point is intimacy. True intimacy doesn’t come from the body—it comes from the soul.’” I cringed at the predictability as much as I did the speech here, but that’s largely the point. Woods hopes to signal us to this pornographic convention: If you’re here for the plot—like Greg is here for the cliché of the wedding speech—you’ve stepped into the wrong theater. Conventional pleasure is rote, its enlightenments reified into its shrink-wrapped avatar. And this is precisely why the protagonist, freshly relieved of her responsibilities at the mansion, finds the wedding guests even more exciting prospects for her services: because they haven’t sought her out. Rather, they’re caricatures of roles you and I may have played at weddings, bit players in a story whose ending is well known in advance. The protagonist, on the other hand, sees in the guests their potential for a kind of revelation that wedding rituals, in their familiarity, fail to produce. Here’s Greg, much later in the book:

He rasped, “What did you do to me?”

“How do you feel?”

“Humiliated.”

“No. How do you feel?”

Greg’s skull dropped to Charlotte’s pillow. His fingers pulled around his cock, light, dripping lotion.

“There’s burning. I don’t know, it’s hard to talk, I—” His chest heaved. “I feel full.”

I fidgeted. I squirmed. I’m an adult, by most accounts, so what happened, and should I be feeling this? But perhaps the modal auxiliary is entirely wrong. After finishing the book, I realized that instead of thinking, the narrator had consumed me into its experiences. It had succeeded, at least for a moment, in reducing me to a feeling body only.Like the figure of the pool boy, Greg is a trope, his ideas about love’s origins in the soul, which I’ll return to shortly, are as sturdy as cardboard, the artifice deliberately transparent so we get to the main event more quickly. “Humiliated,” Greg says, but pressed again, he returns a less precise interpretation: “full.” I’ll risk my own cliché, but here is one example of the book teaching us how to read it. The problem, White Wedding says, jostling our collars, is that appeals to higher ideals about sex—attempts to abstract something like Greg’s “fullness” beyond that—fail to prioritize the physical. And that is precisely what the book implores us to do. It refuses the product copy, the pre-packaged rom-com speech. It wants us to squirm. Because that squirm might just be a pleasure at a different frequency—a pleasure that is difficult to recognize or express in a book that refuses us the firm grounding of conventional narrative focalization. Like Greg, obliterated by orgasm, we don’t have exactly the right words to narrate that physical stimulation. That speechlessness points to the fun in Woods’s book. In another context, White Wedding’s language might be described as crude or in poor taste, might be written off immediately as smut or erotica. But Woods’s efforts imbue the literary with the physical and remove us from vantages that seek to identify personality first and foremost or adopt a posture of authenticity. That’s the point: Woods’s apparently and deliberately smutty prose—what some would label “bad writing”—calls attention to how authenticity is a posture in itself.

How is it that so-called literary fiction, the vanguard aesthetic of the authentic, gets away with badly written scenes of sex—so postured, so contrived, so pitifully try-hard? It’s a question which critics have routinely attempted to address. One criterion for honorees of the Literary Review’s “Bad Sex in Fiction Review” award, last awarded in 2018, was: “Extravagant metaphors are indecently exposed.” Electric Literature took up the mantle in 2020 with its own year-end selection, citing among others a passage from Scoundrels: The Hunt for Hansclapp by Major Victor Cornwall and Major Arthur St John Trevelyan: “Her vaginal ratchet moved in concertina-like waves, slowly chugging my organ as a boa constructor swallows its prey.” An entry from Haruki Murakami’s Killing Commendatore reads, “Her sex . . . would not let go. As if it had an unshakeable will of its own and was determined to wring every last drop from my body.” I hope we can agree that these are bad. “Extravagant”: check. “Indecent”: check. And what about “exposed”?

György Lukacs in “Narrate or Describe?” distinguishes between two temporal modes in prose fiction: Whereas narrative modes parallel the reader’s experience with the protagonist’s, descriptive modes “contemporize everything” and align the reader with the experience of the narrator. Simply put, the first prioritizes the narrative in its time, and the second the time of narration, the present tense in which the narrator . . . narrates. The cited passages above correspond to Lukacs’s definition of descriptive moments: They are about sex, but are not sex. They are analogs that want to substitute for the real thing. This when-ness represents actually bad sex. “[V]aginal ratchet,” “As if”—such rhetoric take us of out of the event of copulation for the sake of a narrator’s experience that speaks for and of its characters, and its attendant valuations are filtered through a narrator, or protagonist-via-narrator, misplacing and dislocating the experience of pleasure for the sake of making it meaningful and purposeful for the interior development of the character. In the Majors’ and Murakami’s deft hands, their metaphors de-sensualize the event in the effort to create so-called authenticity. In so doing, sex’s material existences, like Goop’s products, become more than what they are, paralyzing pleasure in the name of some privileged enlightenment.

These bad bad-sex scenes produce, for me, a wholly different kind of discomfort than the one I experience with Woods. It’s not the referents that make me cringe—it’s the style: “concertina-like waves”? “Her sex”? The sex may or may not have been good for the characters, but because they’re so poorly written, I can’t trust that it was. Because the narrator’s present differs from the narrated present, by the time I read it, the characters’ pleasures are so abstracted that perhaps they can be nothing but the second-hand effects that metaphor relates. If the rhetorical effort is to represent sexual pleasure, then the authors’ literary raspberries are well deserved. Such representations necessitate recollection, reflection, interpretation—in a word, narrative intervention, which inevitably involves a degree of distortion, unreliability even. “Who has had sex here?” we might be inclined to ask. The characters only? Or has the narrator, in recounting their escapades, participated too? It is not unlike thinking too much in situ, too concerned with how they should think about their feeling, how they will look to their partner after they’ve finished—like a partner imagining someone other than the one they’re fucking.

White Wedding, on the other hand, adheres more closely to reproducing the tense of the event than the commentary about what’s happened. The pornographic narrator stays tight to the event and its tense; it plays and replays its material for us and does little else. I realized I wasn’t adjusting myself because of the words alone. It’s the narrator’s uncanny, unsettling reliability. The tight shots demand that its audience see sex, not manage it with metaphor or extravagant copy. It encourages a different, and perhaps more ethical, way to identify with ourselves because it reveals that which more conventional means reify with bad metaphor. Much more familiar, in contemporary fiction, is the technique proposed by the Majors and Murakami. And yet this mode of representation is arguably more morally bereft and dishonest because perspectival interiority dislocates the physical experience, while at the same time appearing, as if organically, to be the realm of authentic identity.Of course, abstraction is part of the medium’s nature. There can be no narrative without a narrator and it would be disingenuous to say that the presence of a narrator definitively forecloses perspective; the merest recognition of a physical sensation implies a mind mediating that sensation into a concept, an intention. And even in Woods’s novel, the narrator does shift from its abstract, exterior location to inhabit the woman’s mind in a more conventional fashion at times. How else would we know that the day is “lovely” as the protagonist finally leaves the mansion? “Lovely” implies reflection on the protagonist’s part, an effort toward representation, rationalization. But to call these “lapses” would be equally inaccurate. Rather, such moments raise larger questions about the book’s aesthetics: Does the book argue that maybe you and I like to be objectified more than we’re ready to admit (at least in the social genres that convene everyday normie society)? How is that different from “ethical” or “fair-trade pornography”? Is that okay to ask? Just as pornography isn’t a substitute for, but is analogous to, sex, Woods knows language, by necessity, cannot accomplish that which her book seeks to achieve: the collapse between representation and experience. But its negotiation of that foreclosure helps us down a more fundamental avenue.What the narrator values is implied by what it lets in. The real main character here is the perspective we have no choice but to inhabit. In that position, the narrator could have elided the myriad sex scenes above, or this one, where Greg’s ex-wife Susan regales the protagonist about how she alighted to his affair with Helen, with whom he is now wed:

She dripped my shampoo all over the floor. That made me so angry. I made her bend down, right there, and mop up every bubble. I made her dig her own hair from the drain.” . . . Her words had slowed, her voice rippling. She exhaled.

The woman seduces Susan to speak, and the narrator doesn’t stop her, allowing ostensibly full access to the time of Susan’s dialogue, like many of the others when the woman gets them going. This models our own position: We’re seduced to keep reading, held by the narrator’s pornographic attention, its repetitive, unrelenting, and unreflective curiosity. For some, it may not be so easy, or at least not initially. Some readers, even you, may find such writing bad, bereft of greater significance—but Woods compels us to look, and to keep looking, and to pay attention to how we look, rather than what it should or ought to deliver, morals managed by a narrator whose commitment to its author is instrumental: didactic, pedantic, smug. Our coincidence with the narrator’s vantage offers revelations more honest and reliable than those promised by the ossified social and artistic traditions of a wedding or a novel. If not a good thing, it is an honest thing. Like the protagonist seducing the wedding guests, the book seeks to seduce us out of our egos—concepts of self which, in the social reality outside of the book, have been trained to be their own best gaslighters, to believe the fiction that we can consume our way into liberation via a premium leather kink set. That this manifestation of kink might be, actually and perversely, conservative.

It’s not the job of the technology—the jade egg, the Instagram ad, one perspectival distance over another—to dislocate your ego from your body. Literal reliability might be more discomfiting than we’d like to or even can acknowledge. Though I have argued that White Wedding attempts to seduce its reader into that enlightenment (if we can call it that), who is it for? Considering the long way this article has traveled, might the book’s aesthetics already be for an even more rarefied audience, one already kinkier and smarter than the naive and misguided one perusing Goop? It is thus a fine line between Audre Lorde’s erotic—located “between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings”—and the pornographic, which “emphasizes [sensations] without feeling.” The erotic organizes and intellectualizes feeling to deploy it as “a source of power and information,” whereas the pornographic “is a direct denial . . . for it represents the suppression of true feeling.” For feeling to be “true,” Lorde seems to suggest, it needs to have its own jargon of authenticity to re-organize the chaotic event into “information” that one could then use for one’s own enlightenment. But this vision has merely led to an instrumentalization of sexual energy, one that plays nice with the PMC. In a chapter called “The PMC Reads a Book,” Liu writes that “PMC elites are always experimenting with themselves . . . their self-indulgence is always a kind of sanctimonious austerity.” Lorde’s specialized erotic vocabulary is for those smart and hip enough to know what authentic sexual pleasure is, unlike the rest of the unenlightened plebians. But such self-fashioning presumes a stable ego on which to experiment, and hence a return without damage or risk. Who can afford a more optimized self to indulge with either restraint or binge? Recall Greg’s post-coital report (“humiliated . . . full”). The first needs an ego to recognize a change in feeling, but the second merely describes a bodily sensation. If the first is erotic, the second is pornographic. His experience is illustrative because of his arc in the story. We meet him as the drunken father of the bride who rehearses cliches about love, that love demands “trust and listening and forgiveness,” and who bemoans that “our culture teaches young people . . . [to be] obsessed with appearance and expression and pleasure and who touched who, and how, and what’s out of bounds.” It’s his response to the protagonist’s work, “‘full,’” that seems to carry the most potential for enlightenment out of the rest of the characters, and this is precisely because of his position—it’s the father’s traditional notions about sex and pleasure that stand to fall. But it’s also his three-story house, and while we don’t witness him recover from his orgasmic stupor, the best we can assume is that he’ll keep his experience as a secret, perhaps almost doubtful that it ever happened, and return to the status quo. So while Woods would eschew the necessity to delineate the ego from Lorde’s “chaos” of desire, to transform it into a technology of the self as a way to “measure” its worth, we must nonetheless wonder if Woods’s more modernist allegiances are any better an intervention. Can a pornographic narrative style really do anything?

We ought, rather, to interrogate the question itself. To ask whether the pornographic narrative style does anything (and to value it accordingly) is to buy into the promises of virtuous consumption. It is to believe that consuming a book somehow transforms aesthetic experience into social action. Perhaps the greatest achievement of White Wedding is that, for all its potentially alienating scenes, it demonstrates a sincere respect for its reader, and it does not try to feed us such a promise. It is a commodity, indeed, like everything else is, but if it didn’t do it for you, oh well. While Lorde’s erotic vocabulary enables individuals—a particular class of individuals—to define “true feeling,” Sontag and Woods gesture toward a more universal experience with no prerequisites. It urges us to consider on and against whose minds criteria of pleasure and transcendence are modeled, and it respects and believes in us enough to leave us with the question.

White Wedding isn’t an instruction manual, nor does it, in Mitchelmore’s words, “tackle” its content by means of calling attention to its own virtue. The wedding guests do not rally around the protagonist, nor do we know what happens to her; like the former, we’re left in a post-coital haze, at a loss to ourselves. And while it never says as much, it could point, however slyly, towards deeper it a criticisms about aesthetic interventions into politics, and to question whether those aesthetic experiences have any right to be identical to the latter. It challenges us to strive for what could be really, materially different, to hold in tension the desire for authenticity and the myriad ways it’s commodified in our times, lest we succumb to what Borczyk would term an inevitable “self-commodification,” where we repeat advertising copy because it sounds like the badly written metaphors of sexual pleasure, of enlightenment. White Wedding’s overt contrivances are an exercise in authenticity. Unlike the $149 gold-plated Goop vibrator, the book does not pretend it is more than what it is. Thus it holds open the possibility that authenticity is not lost to performative appeals to progress that re-entrench those same social and cultural hierarchies they ostensibly resist.

You may find it difficult to start a conversation about this book. Much less an easy one. That’s good. Might I suggest you begin with your favorite scene, because you definitely didn’t read it for the plot.

Ryan Chang lives and writes from Los Angeles, CA. His social media is @avantbored.

This post may contain affiliate links.