[Game Over Books; 2023]

In Emily Stoddard’s debut collection of poetry, the whole of the world is calling—its darkness and its lightness alike. So too call the afterlife, memories, dreams. So does the body. So do imagined paths not taken and the stories we’ve always been told are true. This book, from a friend of mine, collects artifacts from the world around us as indiscriminately as a magpie and brings them inside. There is something familiar in every poem—a doe’s nose nudging a palm, a “soft pod of milkweed,” a book of love notes to a husband, a plaid skirt for church, a verse from the New Testament. Nevertheless, each poem revels in staggering unfamiliarity and wakes up something different inside us.

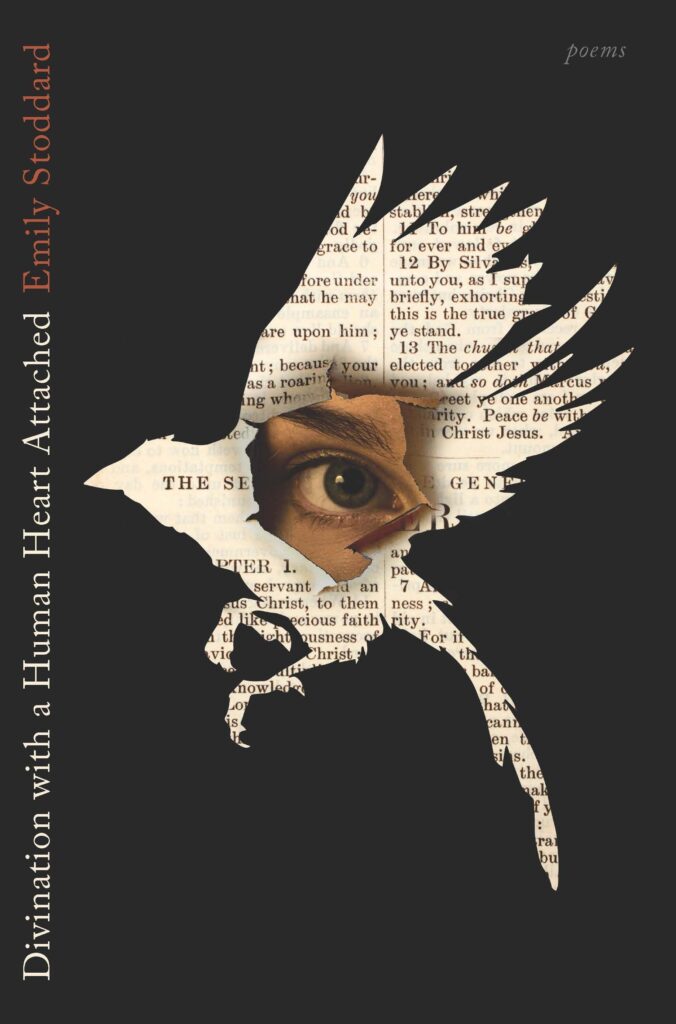

Divination with a Human Heart Attached is divided into three parts, with a magpie sitting knowingly at each entryway. We are told that when the world flooded, it was the magpie who refused shelter in the ark. When Christ was crucified, the magpie was “the only bird / who chose not to sing or dress / in mourning.” In the collection, the magpie has an endemic knack for faces. She can even recognize her own in the mirror. Be aware: She can tell a good face from a bad one.

The book opens in section one with “More & More,” a poem whose speaker awakens with other languages in her mouth and grounds the poem in a plea: “Tell me it is only human— / to wish for someone to believe / in the myth of you.” In this section, the myths of ourselves are skillfully braided with the myths and stories we’ve been fed. We feel what it’s like to sit in a tight confessional booth, but also how it feels to leave that box, to shrug off that kind of confinement.

In this opening section, we first meet Petronilla, daughter of Peter, who ponders her father’s prayer and ultimately, her own fate. She sits with us throughout these poems just as the magpie does. Petronilla becomes paralyzed on one side of her body after her father’s prayer to the Lord about his disdain for her beauty. The reader can’t help but wonder if it’s Petronilla in “I was running to him” who recounts that her braid coming undone is the last thing she feels as she falls at her father’s feet, “heavy body / broken lion / answered prayer.” The reader is still thinking about this girl and her body late in the book when—in “My father saw me once”—the speaker counts herself just as much of a miracle as the talking dogs and resurrected fish spoken of by the men around her.

The body is a constant artifact in this collection. Stoddard explores the ways in which the body can die and the ways in which the body can continue. The body of a girl is held within the egg of her to-be mother, who is carried in her mother in “Inheritance Rosarium. “If it’s true,” the speaker concludes, “if god is there at all, she kicks us from the inside.” We encounter “Swoon Hypothesis,” which explores what might have happened if Jesus had not died on the cross, but instead had lived—a fascinating alteration of the story. The body is heavy in these poems, but always alive. Vital. The body is a redwood tree then a black walnut in “Revisionist History”: “Lightning strikes, / I burn / from the inside . . . Cut my leaves, / I grow / a new face.”

In section two, the poems really begin to take stock of themselves. As Stoddard cites, “One for sorrow, two for joy, three for a girl, four for a boy . . .” and so on comes from a traditional nursery rhyme about magpies, first recorded in the 1700s by John Brand. The men in this poem are grieving—Judas himself is grieving—and it seems to be the magpie whose magnetic blue feathers the speaker swallows in her mouth who reports what these men are doing with the grief that is “too much for their bodies.”

Echoes of the crucifixion are never far from the poems’ consciousness. Instead of Jesus, the speaker’s father wants to be the disciple Peter in “Passion Play.” This poem incites such a richness of imagination; how affecting it must be to see your own family member crucified in a performative reenactment. “Every year, I find a little more of the broken alien inside of him . . .” the speaker laments. “Every year, the slashes get wider.” Here, Stoddard skillfully blurs the line between story and reality.

And there are other sources of grief in these poems: a first marriage that ends, a robin that collides with a window. “Upon watching her collapse in the dirt,” the speaker writes in the book’s titular poem, “the first instinct was a tenderness: Would she fly again? / But the answer was hungry and familiar: With these wings, what omen?”

In the last section, the one in which the reader is told a magpie has a long memory, the artifacts collected are among some of the most poignant and painful. Like death. We have been thinking about the death of Jesus, as in the poem “Seven for a Secret,” which seems to ask the reader to consider what Christ had left inside his body the moment that he passed from one world to the next. But this section brings death closer to home. “They say you should hold / your breath when passing the cemetery,” the speaker says in “Crabapple Elegy,” “but I do not fear the reach / of the dead . . . I learned the sounds a body makes / as it unhooks itself.”

In addition to the unhooking, these poems leave us with a gentle litany of things left behind—things more suitable, perhaps, for the more subtle shades of grief. In the longer, more prose-like piece “It embarrasses me, to see myself,” we dwell in the list of a lost engagement ring, an abandoned orchid, “[a] bluebird that was not a fortune teller after all.” Even the small things we lose or leave behind often leave a permanent mark.

Stoddard returns to Petronilla—and the body—in the last iteration of the daughter imagining her father’s prayers. By this point, the myths and the personal have become so entwined that the speaker seems to be speaking for so many women when she invokes the lives of “all the daughters the body carried inside of me / dreaming those dreams.” In a late poem, “The Worm,” we wrestle with tombs and wombs, how words like “good” carry their holes in their centers.

“Tomb” also carries its hole in the center, the poem’s speaker points out. So does “womb.”

In Divination with a Human Heart Attached, Stoddard writes with such fierceness that the poems follow you for days, repeating their lines and whispering images into your ears as you go about your daily tasks. With incredible range, these fearless poems envelop a breadth of emotional experiences. There is an otherworldly quality to these poems, a certain ethereal nature. Yet the poems keep pulling you back to Earth, back to the dirt, back to the realness of life. Real life is a marriage of truth and myth, history and future. Life requires divination. This one is astonishing.

Colleen Alles is a writer and native Michigander. She writes fiction and poetry. Her collection, After the 8-Ball, was published in 2022 by Cornerstone Press (University of Wisconsin, Steven’s Point). Her latest novel, Master of Arts, is out now (Scantic Books). She is obsessed with good coffee, distance running, and her beagle, Charlie. You can find her online at www.ColleenAlles.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.