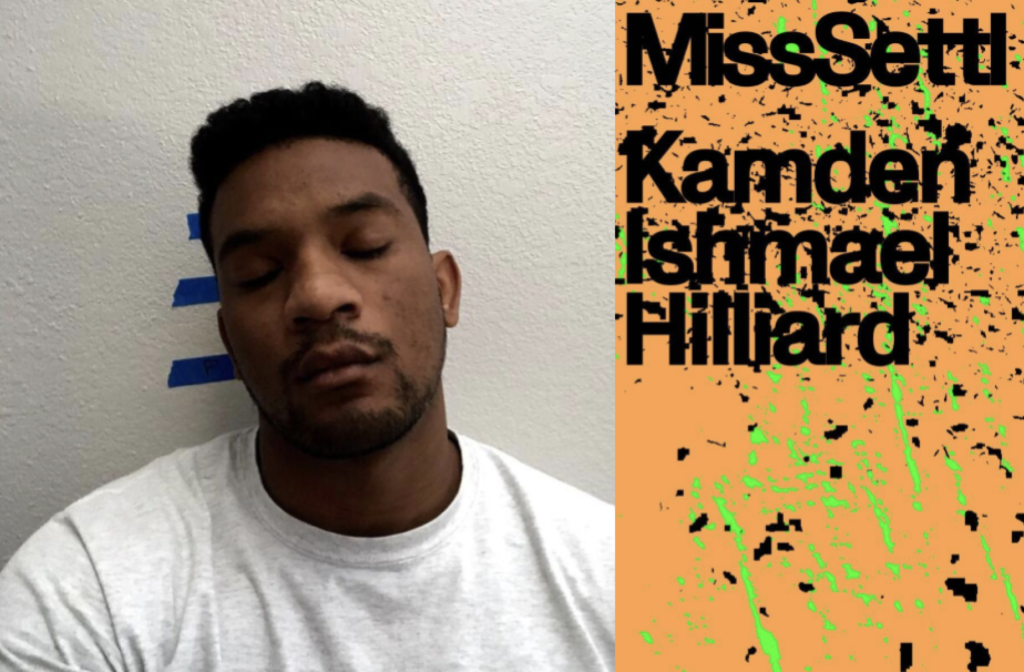

Kamden Ishmael Hilliard’s MissSettl, published last year with Nightboat Books, is a highly inventive and rigorously composed book of poems—and my favorite of 2022. What sticks with me upon seeing this interview in its finished form is that Hilliard’s thinking about poetics, and, of course, the poems themselves, reveal a refreshing commitment to advancing far beyond the acts upon which another poet might rest, self-satisfied. The power of these poems—and this interview—comes from Hilliard’s demonstration that there does exist the potential for further capaciousness and plasticity—of language, play, singing, thought, and (importantly) imagination—which can be enacted uncompromisingly against the internal and external sanctions that would seek to limit such efforts.

PM: What is the strangest thing you know to be true about the art of poetry?

KIH: That poetry can change the material world (and the non material world!). That poetry, as An Duplan has said, “is the social life of language” (heard during a lecture at the Cleveland Institute of Art, Fall 2020). That poetry, often, goes unnamed in what Bishop’s “Questions of Travel” describes as, the “rain / so much like politicians’ speeches: / two hours of unrelenting oratory.” That poetry so often hides what is essential to us, say, how we get around, inside language dull and rainy as infrastructure. That all extant things maintain a relationship and in the maintenance of any relationship lies the formative instincts of any poetics. That my poetics, unlike my tics, quirks, looks, and laugh, underwrites my ability to detect, perceive, and coexist alongside Life. That poetry is, as Plath says, “a little music machine.” That poetry is magic! That Plato agreed! That, often, poets attack on the plane of the vibe. That like any tool, poetry can do all kinds of things. That poetry goes nice with neoliberal priorities. That between truth and beauty is nothing and that the whole question is such an odd location to offer anyone; that if I ever find myself split between truth and beauty that I am not in fact split but instead tired and in a bad mood and that I am having my imagination foreclosed in a way that renders all further effort dull if not harmful. That poetry is free! It never costs money!

Are there certain parts of the art of writing poetry, of poetics, of prosody, that you’ve always relied on? Are there ones that you feel that you can lean on more heavily, or that you feel an impulse to lean on, or are the most natural when beginning a poem?

I am moved/triggered to write when in my ongoing thinking and feeling life I encounter a cliff, which, when I try to let go of, returns to me in greater detail than before (and by cliff I mean place where my thinking-feeling are not yet at ease, or a place that, were I to travel there upon its discovery, I would not return; and if I did return, it would not be me doing the returning).

In other words, one day I notice that what I’ve been calling a creek across from my place is a brook; the next day I wonder about the difference—a week later I am asking my students about the brook (Doan Brook), I am learning more about salinity, rocks, sewage overflow, local environmental controls, the locations of other rivers, creeks, brooks; eventually lakes and ponds; eventually this thought turns into a short poem about some roots down by one particularly lovely bend in the brook. The roots were so straight and set so well apart that I thought some Sierra Club/parks-and-recs folx had laid down lumber stairs for ease of access. No. Those were tree roots. And it made me feel something to have mistaken them for parts of tree corpses. I wonder about what has been done to my looking and have arrived at the beginning of a poem.

Frank O’Hara’s “Why I am not a painter” is a better version of this joke maybe (read it!), but you get the idea. In other words, I use whatever strategies I have—research, rhyme, song, exercise, ritual, walking up and down the goddamn brook—to move over that cliff of thinking-feeling, and through language, to offer some crystallization of that experience. I offer that crystalized language in the hopes that other people, when poised at their own cliffs, do not turn away, but slowly rappel down, using whatever strategies they may have to enjoy the risk. Lol, to survive the risk.

And as far as beginning goes, materially, I am absolutely trying to start the poem late as possible. In my poems, the party is not only already started, but it’s beginning to leer and display its conclusion; the state is failing/ed and the pressure is what moves us into the room/meadow/riot of the poem. Also, it’s the economy, stupid. Crisp. Crunch. Or, waiting till the last minute makes the poem primarily a device moving behind its subject—I love this, I need this, this is my experience. In this way, the poem becomes a raw-er vector, consumed, and obsessed with the basic challenge of documentation, even while doing the pattern work of language. Like, if we still discuss the reality of antiblackness as an open question, what are we to do with the lived (and made dead) experiences of Black people?? Not sure, but my interest in “beginning” feels like a kind of hunger for the end of evidence as a kind of love.

So, I think I understand this to mean, in one way, that a poem’s pressure comes from the weight of the reality of antiblackness, of a failing state, but the poem is like a body or voice or experience living within these facts, and not necessarily trying to articulate it because it is?

If so, how does that square with the obsession with “the basic challenge of documentation”—does that mean that there is a kind of articulation happening, but just not a discursive one?

I am either uncounted or counted twice; this is the basic problem. Excess or Lack. Black people are murdered by the state, then that same state wants an MLK Jr. day. Can you believe there was an MLK Jr. Day but no anti-lynching law until 2022? Can you believe it took around two hundred times to pass that anti-lynching legislation? I can. I have to. My ability to understand these ridiculous contradictions is not unique, but necessary.

Alternatively, the only thing I find to be happy about is my unhappiness, my rejection of pleasure underwritten by white supremacy or its money or its cousins (patriarchy, capitalism, etc.). I grew up on the island of O’ahu on a military base, in Mililani Makua, Kāneohe Bay, Mānoa Valley, and Ka’a’awa, on the north shore. I lived in “Hawai’i” insofar that it is an illegally overthrown Kingdom. I did not live in Hawai’i insofar that I was indigenous to the land. I lived in Hawai’i, insofar that I had a driver’s license, some friends—what I am trying to say: I lived in a socio-legal infrastructure protected by the always implied threat of violence against Indigenous populations by military, Asian, and settlers of other kinds.

I am trying to say that even something as static, as boring, and allegedly tangible as “place” is impossible to articulate, even once maybe. Like, literally, if you can’t step in the river once, how on earth could I describe anything? Also, lol, it’s not that serious, but I get stuck in this part of my thinking.

More generally, if Hawai’i is a paradise, for whom is it a paradise? If paradise is a place we travel to, what might that mean for the Indigenous people of those places, those who are there before the tourist arrives? Is tourism in a helicopter still just normal casual tourism or a behavior on the spectrum of war time surveillance? How must paradise be secured? Are there houseless people in paradise? Yes! There are! And what might it mean to leisure in the face of these inequities?

I am also wondering if there are any techniques or strategies you’ve consciously been interested in abandoning or at least closing off for any particular reason.

Mm, well, I’ve resisted prosody. . . but now I write in syllabics (see Elizabeth Alexander’s “Lazy,” & generally just see Elizabeth Alexander—two faves: “Affirmative Action Blues, 1993” and “Boston Year”). I mean, generally, I am interested in moving away from some traditional techniques of speech. I mean, less generally, that an English operated under white supremacy is certainly an afflicted language. I am stuck in that language, and in some ways, I love it, and in more ways, it refuses to express the full intimacy I would like to offer. I like to think about the breath as a palate for the line, when we speak we modify, control, stop, change that breath, we shape it with our tongues, lips, and mouths. In other words, I try to find units of language which can be suspended, in real air, and explored by myself or a reader. Also, I like thinking of the poem as a kind of schematic, or sigil, something determined by its final shape.

I do resist the sentence, the container which is supposed to hold one idea. There is no one idea. I struggled with grammar as a child and once I developed some mastery over it, I began to collaborate with its edges and failings. Further, reading Fred Moten, da Powell, Natasha N. Nevada Diggs, Doug Kearney, and other pushers of the sentence and line helped me realize that: (1) my desire to escape grammar is not singular! I am not alone! and (2) If one escapes grammar one must take on the responsibility of forming an organic system of meaning.

Harryette Mullen’s Sleeping With The Dictionary, also, became almost a command to try and encounter the truth blinking out between the variant, always crowding lies. So, I think, generally, I am interested in new grammars / anti grammars as landscapes where genuine articulation (ok fine my genuine articulation) is possible, expected, and exciting.

Was there a poet you encountered first who was the strongest early guide for you in exploring new grammars / anti grammars?

Oh yes, Joe Tsujimoto was a wonderful poet and teacher who worked at Punahou School in Honolulu, HI. I loved him. Hawai’i is a very racially diverse place, but it is also a site of Asian settler colonialism. My brother and I, along with two other sets of siblings constituted the school’s Black population for a decent time. Tsuj helped me understand the relationship between myself and the world, really. I had no sense of “politics” at the time (neoliberalism is really always like, nah history was wild! y‘all just missed it! It just ended!) and he helped me start to see myself as a person with concerns in the world. He also got me some sense of the sentence (and I was in eighth grade!).

I met Terrance Hayes’s Lighthead as a gift from another Punahou School teacher, Liz Foster (Liz Mom oh do each and every one of us miss you). She gave it to me at the end of a seminar and remarked that this Terrance Hayes person is up to some things I will want to see. Liz was wonderful, an older white woman whose classroom was an oasis. This moment, too, was a grammar: I realized that one of my jobs (as a teacher) is and will always be to help people find out where they might need to be going.

I mean, then there’s Terrance Hayes. Lighthead became a model, lodestar, and guidepost for years. The rage, tenderness, humor, ugh! It was so hot and funny and sad and it taught me that those neat barriers which I’d arranged around in my head, demarcating what is and is not fit for poetry. . . I realized that those barriers were very mean spirited and dangerous, as most barriers are.

Harryette Mullen’s play changed my sense of resilience and general outlook on the world. The Abecedarian has become a life-long form, as well as the prose poem. And, too, like Terrance Hayes in his “Harryette Mullen Lecture on The American Dream.” I love to put my Harryette on! And what is that? It is risky, intellectual, rigorous, Black, associative, rhythmic, funky and muscular music for an aftie run by those thinkers too dangerous, Black, or otherwise real to be admitted to any University. You think she’s out here joking and rapping and she is . . . but she is not . . . Play as a preemptive strike. Play as an analytic. What do you throw at the most well armed nation-state (gang) in existence? Sometimes, jokes. Also, she taught me to identify what wants me dead, even if it’s invisible, stacked up in a trench coat, or included in the parking lot’s disclaimer (please, please read “We Are Not Responsible”).

Can you think of a particular time or instance where it occurred to you more consciously that dullness or a foreclosure of imagination was something that you saw as a danger? Was there a time in your writing life that came before this realization, or has this always been a part of your relationship to poetry?

Yes. The institutionalized writing culture (the MFA, the workshop, the national writing conference, strictures of publishing). . . all normalizing, regularizing technologies. . . to participate in these places, you must remain legible to them, and them places particularly. Now, what governs this legibility? How about. . . an appreciation for the Western Canon? Better: just knowledge of the Western Canon? Perhaps legibility is governed by one’s socioeconomic status, heritage, history, or one’s willingness to develop and maintain relationships with “professionals” in the field (which so often turn out to be Scooby Doo villains).

The confines of legibility go on and on, and they change locally and nationally, and they never really change all that much actually, lol. Are you formal? Are you experimental? Are you lyric? Do you defend the neoliberal and new world orders? Do university creative writing departments improve students’ lives? Can you just talk about poetry, and not questions of power, access, literacy, and harm? And if you can’t or won’t, what will happen to you? These patterns / structures help us understand who writing / poetry / verse / literature imagines itself for. Who writes these stories and how do they reify one of many possible histories? This normalizing structure is a site of play, slippage, and reversal. Like any barrier or form or rule, we can use it to build different kinds of momentum.

Could you talk further about what you mean by using barriers of legibility as momentum? Momentum seems to be an essential aspect to your work for me as a reader, and I wonder what that means to you.

Yes! If poetry is a magic, one of my favorite magics is the magic of escape. The magician is lowered into a tank of water, she sits locked in a chest chained to railroad tracks. . . what happens next is almost unbelievable, but so incredibly necessary! What a jolt! Everyone gets a kiss! Everyone lives (we hope)! So, for me, I am surrounded by walls, walls always moving closer, so instead of getting squished, I use them to parkour the fuck up out of there. Joking, but, really, what else to do with the uniform and totally individual wall of white supremacist techniques of violence? Take its momentum, turn the joke back around, refuse the name, rename, rewrite, unwrite, write out.

If you refuse to understand me, fine. I will work away from understanding, I will dive into my own (un)knowing and make something else instead.

Would you be willing to say more about poetry and its complement to neoliberalism?

Yes! Often, poetry is imagined as a life-affirming practice. This is a bit too uncomplicated for me. I might say, instead, that poetry is a life-oriented practice. The difference? As there are charms and spells of protection, there are hexes and curses. All magic. I agree with CA Conrad when they describe poetry as magic, and for that reason we must track its intentions deeply and widely. A deregulated poetry, a poetry without memory, culture, or history, risks becoming merely speechifying, politician talk, bullshit, gilded lilies, and the like. Donald Trump’s strange syntax and diction, too, are a poetics. Poetics are not universally good!

Is poetry a complement to neoliberalism, then? No, probably not. I think poetry, as a craft, as a technique, as a meaning-making place, is vulnerable to comfort, perspective, and questions of identity. Whiteness, any dominant identity really, tends to take “comfort,” instead, for, “the continuance of white supremacist structures which guarantee my ease in this world.”

Do you think that to get at that Conrad magic you mention that a poem’s grammar likely will be disruptive to hetero/hypernormative, white supremacy-developed exclusionary grammars? Where do you stand on the “masters’ tools” argument?

I think when we say “magic” we often think of it as a concept, but I think I mean more about energy. I think magic, as a system of energy or meaning or seeing or feeling, does not carry a valence. What white people have tended to imagine (forcibly and aggressively, may I add) as “Black magic,” or transphobe-Rowling’s “Dark Arts,” implies any negativity emanating from the magic practice as aberrant. That is just not the case. As I mentioned, the curse and hex lie alongside the charm and balm. Rhetoric has no team, rhetoric has no flag.

Perhaps I mean—work which comes from any system, will, in its smallest units and refractions, exist squarely within the language and meaning of that system. Carbon based as carbon based: of the sea; of the air; of the land.

Also, consider standard grammar’s use. If we do live in a late-stage empire hot on death, what kind of languages, which textures, vocabularies, and vernaculars manage to live on? What kind of language might be available to us after the downfall of white supremacist capitalism? The same ones now. Choosing them would just not mean illegibility, lol.

This is my point, legibility is not merely syntactic, it is also political or aesthetic. Example: my students use techniques of bolding and font change in workshop poems. I love this. Go get um. However, when those same students ask for help preparing a packet for a contest, I ask them to remove these boldings and fonts. Why? Because they are not terribly legible techniques to the coterie of graduate students and professors who adjudicate these contests.

So, in response to the master’s tools, I flee gleefully. I take flight. Others, I imagine, beat the fuck out of them and fight. Generally, though, I think we must decenter traditional practices. So, while we ought to use them, occasionally, perhaps we also ought to plan for their impending decommission.

When I read your work I always wonder (even in spite of you mentioning struggling with grammar as a child) if you were always playing with language as a child. Was there a moment when you also saw that gesture of play as important to your aesthetics or to the way you wanted to make poems?

I was taught to at least want some discipline, then I kinda learned some, and now I am actively working to undiscipline myself. What do I mean? I want to unbundle, relax, chill out, calm down, take it easy. Previously, I thought that if I could stay in pain long enough, I’d earn some miracle shower of hugs and money and love. Alas.

Now, I did love fiction as a child. Anything with a magical land? A magic power? Game. And now, I do recognize something as trad as The Boxcar Children as a major primary site of narrative and thematic experience. I can still remember parts of Shel Silverstein’s “Sarah Cynthia Sylvia Stout Would Not Take The Garbage Out” and Jack Prelutsky’s “Homework, Oh, Homework.” Clive Barker’s Abarat books were a long favorite.

The movies from childhood I remember well: All Dogs Go to Heaven 2 (1996) and Catch Me If You Can (2002). Are these things playful? Well, they play on the edge of the law, they play fantasy and magic. . .

What I can say is that some of my best memories were being knee / elbow / toe deep in these stories, these stories about so many people who. . . for lack of a more discreet analytic. . . tried it and kinda won?

What for you has the art of working in syllabics revealed to you that you perhaps did not expect?

That I was working in syllabics before I started thinking about it. That surprised me. People have wonderful ears. Let folks work with their ears and they end up not too far off from rhythm. This is not always the case, and I think working intentionally allowed me much greater control of the bits and bobs of the poem. Now, rather than intuiting how my sound and (nonce)sense collaborate, I am able to specifically and deliberately shape the line’s muscle. Also, idk who, but we desperately need a study of hip-hop as the avant garde of syllabics, meter, wordplay, bars, feet, beats, and many other aspects of verse.

How much interest do you have in perhaps continuing to work on, reimagining, or revising your work—in thinking about how a reader might experience it?

Oh yes, I don’t really finish poems. I think I will be working with some of these poems for the rest of my life. They don’t always need to be what they were anymore. Poetry is therapeutic for me and occasionally, in revisiting old work, I realize that I no longer need the poem to hold what it’s holding. In those cases, I think about what the poem might hold now. They grow with me, I think. They get kinder and wiser over time, well, lol, that is my hope. Also, I am realizing that, for me, a poem is a kind of thought, for me, a genre of thought. The poem makes accessible, makes open, takes us further and further from isolation and loneliness.

Because you mentioned that you often begin with questions, I wonder if you could share how you began MissSettl?

The original title of this book is Educational History. I wanted to think about the conditions of modern education and where it occurs: in bars, clubs, libraries, hallways, classrooms, athletic fields, dark movie theaters. . . And, I was interested in the formal difficulty of minority self actualization in a system of education that promotes white thinking, settler colonial histories, etc. . . Also, I wanted to know more about what whiteness has done to me. We always talk about “toxic” masculinity, but I think we need to mean more. I wanted to think about the proximal effects . . . what does being close to the heart of money do to the body? The mind? And if the only way to stay alive in this arrangement hurts so much, what, exactly, is so lovely about living to only extend the stick/rod/law by just one more set of hands?

What resonances/meanings jump out for you when you look at the title of your book now, if you were to tease out some of the possibilities/phrases/sounds embedded/hidden in it?

Best at being a settler colonist, at least for a while. Miss. Missing my home settlement. To settle in, relax. To settle, destroy. To settle, rebuild. To settle, lie. To settle, militarize. Missing what would happen instead of settlement, missing the alternatives. Missing you! Missing me, a loneliness for all us three. Confused speech. Contested speech. In a dreammare, I can imagine the title printed on a pageant sash, pinned to my chest, and then, I get a head start. I just, literally, lol, run—

Peter Mishler is the author of two books: a poetry collection Fludde from Sarabande Books, which won the Kathryn A. Morton Prize in Poetry, and a book of reflections for public school educators from Andrews McMeel/Simon & Schuster. His new poems appear in The Paris Review, The American Poetry Review, Granta, and Lana Turner Journal. In 2019, he was interviewed at Full Stop about Fludde.

This post may contain affiliate links.