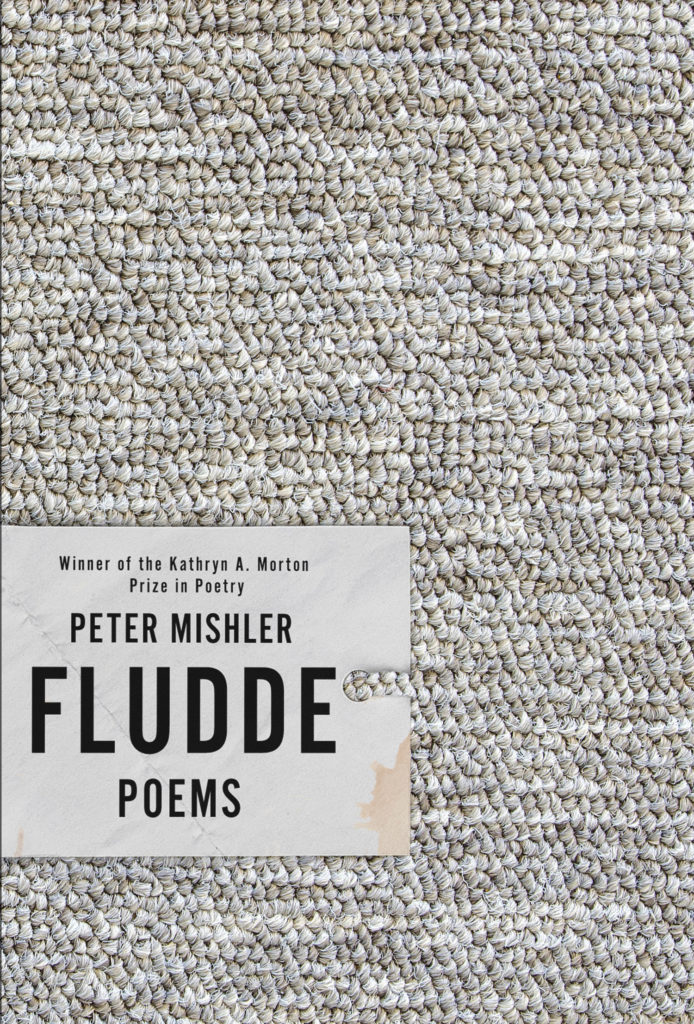

Peter Mishler’s Fludde (Sarabande, 2018) is a tender, wonder-filled, playful book of poems that juxtaposes the wide-eyed nature of childhood with the seriousness of adult life, with, as the speaker in one poem articulates, “the detritus of waking life.” There are myths and sicknesses and motels and frustrations all circling one another. Reading the book feels like stepping into a theater where a play is occurring but no one is in the audience. There is uncertainty there, but also intimacy. The end result is somewhere between critique and gorgeousness, this surreal disruption of all we see in front of us. I had the opportunity to speak with Mishler about Fludde, as well as themes of boyhood, gratitude, and more. It’s all below.

Devin Kelly: Boyhood and, more generally, childhood, are prominent and affecting themes in this collection in ways that are wildly multi-faceted. There are elements of play, but also helplessness, tenderness, wonder, and, at times — such as in the ending of “To a Feverish Child” — a sense of frustration in looking back at childhood from the adult’s perspective (“What do you have to do but wait…”). I’m wondering how you access these themes in your writing, how you write into childhood.

Peter Mishler: When I was writing this book specifically (the work I am doing now, while similar in subject, is different in terms of approach), I was waking up early to listen to a voice that seemed to be coming from somewhere in my chest. It only seemed to be there in the early morning. Not my head, not my heart, not my “gut,” but somewhere between the stomach and the heart, someplace in the tissue there. I tried to write what I was hearing as best I could, and as I worked, I found the regular pattern to this voice, and I became a better listener, able to follow its cadence more closely. If childhood, one of our earliest identities, always remains with us—especially if we are bearing with us, as adults, its inevitable hurts—I think that this must have been the voice that was speaking. Then again, if we also bear with us all the detritus of waking life, all the garbage that is imposed on us and that we are exposed to—the nausea of billboards, as Baudelaire quipped—that voice was coming through too. Maybe I was experiencing the unavoidable polyvocality, the dissonance of, being an adult and a child at once, and I found, I think, a collision of those voices in the resulting poems; and therefore, the drama of the book, I think, is a childlike encounter with the adult world and an adult encounter with childlike imaginings.

I love that response, and I am particularly interested in how you began that by saying that you are doing different work now. Does the work you are doing now still attempt to access these serious, stubborn things — such as the “detritus of waking life” — and if so, how does it do that differently than Fludde? I ask because I am interested in obsession, about the idea of forever writing towards similar ideas and pains, from different access points.

One of the things I think is different in my new work is in the verb I would use to describe the method: “access” seems fitting for Fludde, but “attempting” seems more accurate for the new poems. As opposed to a kind of “method” that was focused on becoming a conduit and letting go, I have grown interested in feats of consciousness, purely because they are new to me, and unfamiliar, and therefore disorienting. One of the things I admire most in a poem is its clarity, which does not come naturally to me. Or at least it is something I obsess about and wish for while admiring it in the work of others. So, in an effort of consciousness and clarity, I’ve written a pastoral, a sonnet, and a long narrative poem. All of these will appear soon, and they all required a different kind of work from me because of the necessary restrictions of form and genre, and this was all pleasurably time-consuming and something I could think a little bit about while I wasn’t writing because my responsibilities to my family give me less time to sit and let the spirit move me, so to speak.

That’s so interesting, the juxtaposition of restriction and pleasure, that such “necessary restrictions” led to a pleasurable kind of work.

I found playing with a sonnet’s rhymes in my head while wading in the baby pool with my daughter especially sustaining. It feels like a derangement of the senses to write as clearly and intentionally as I can (as if the “truth” were such an obscure or experimental idea!). But to your point, the new poems are probably circling ideas that are similar to the old ones and even if the level of clarity is only a touch more than in the poems from Fludde I will feel like I moved forward. That being said, because my writing life tends to mirror my psychological growth, I hope the new work demonstrates a change in that regard as well. I don’t feel that I am now smarting as severely from the wounds I was experiencing while writing the first book. I also don’t feel like I am writing for myself as much as I am for someone else. Writing my first book was focused on accessing and healing psychic pain. This manuscript is intentionally being written for my second child, my son—an attempt at communicating something to him. My focus feels very direct and outward.

In relation to that last question, I’m thinking too of those lines, in “Mild Invective,” where you write: “I feel I must become / religious for a time.” If I am allowed to pick favorites, that poem is certainly among them, for so many reasons. One tension that crops up in this book is the same tension that exists in the title of this poem, or in the speaker’s want to become religious but only “for a time.” It’s like anger stifled by tenderness, or an open-ended faith. Can you speak to this?

My first instinct is to respond to the stifled anger you’re reading in these. When I read the book, I see it as a psychic map of my own struggling and healing, and because this was an earlier poem written for the book, I know I was a poet who perhaps circled pain as opposed to meeting it head on—someone who was unaware of an underlying anger and grief. As far as the open-ended faith, I think of children this way to some extent. The enormous capacity for love, and a desperate and even self-preserving desire to make sense of the world, despite its failures. If the book is a psychic map of the “self” and my subject is perhaps childhood and its collision with adulthood, then what you’re reading makes sense to me, too, but in hindsight, of course.

I think of circling a lot when I think of poetry. Whether circling pain, as you said, or any other point of serious emotion, as opposed to colliding with such points directly. Do you think of poetry in a similar way?

I do, and think that’s clear from the poems in Fludde, but I have always been taken with very direct, clear acts of speech in poems. I am thinking especially of the opening lines to the madrigal poems of the 14th, 15th century: “On earth shall sorrow be.” “Red, red, red is the color of my true love’s hair.” “To hear men sing I care not.” These opening lines are remarkable to me for their beauty, determination, directness, and clarity. This is what I am striving for, though my imagination gets in the way. Imagination has been a self-preserving, self-protecting force for me as well. Though I think now that I feel more comfortable in my skin, that directness is coming through. So in my case anyway it’s my experiences that have determined the approach.

Thanks for this answer. I find it fascinating because I feel sometimes the need for myself to destroy the relationship, in my own work, between the “I” of my poems and the “I” that I am, rather than using the poem as a vehicle to explore honesty and truth. Do you have any thoughts on this relationship between the self that writes and the self that exists in the poems the self writes?

I often feel like it wasn’t me who wrote my poems and that I have no idea how they got written, after the fact. Even with these new ones that are very intentional acts of form or genre or with a specific narrative endpoint in mind, I still look at them and think, “How did this happen?” and “Who is saying this?” and then I feel grateful that I’m not really sure. I feel gratitude, mainly, that I am aware that there are voices within me more intuitive or more imaginative than my own, and that I can still in some way claim as my own. I feel gratitude to know I have an outlet for abandon, especially as I struggle to be more outwardly expressive and unrestrained in my waking life. I like having a space where I can perform as someone who is more forthcoming than I feel I am. It’s a good place to work these kinds of things out for myself. One of the biggest learning experiences for me in writing Fludde was: “If I can write it, if I can write this way, what other areas of my life would benefit from getting my brain out of the way?” I find myself very fortunate that my writing life seems ahead of, and can accomplish, the challenges of my personal life, and can offer me a map forward.

I love when people talk about gratitude. And when people talk about the relationship between a poem and its effect or ability to transfer to a way of understanding or acting in life. I think of how Alice Walker said: “Deliver me from writers who say the way they live doesn’t matter.”

Because the writing of Fludde also tracked, or—more likely—anticipated psychological growth, and because that psychological growth has led me toward greater well-being and health, I can’t help but see the dynamic relationship between poetry and one’s lived experience. But then again there are so many poetries and lived experiences behind them, I can only speak for myself—and certainly I must acknowledge the privilege that is evident to me when I think about how fortunate I have been to explore interiority at all, to let my imagination to be preoccupied with poetry, and to choose, to some extent, to aim my writing in this direction because so many other basic dignities of life have been met in an utterly inequitable country and world. And to know that this is the case, this always turns me outward, toward thankfulness, toward my family and also my students.

In some ways, these poems remind me of asymptotes, of Xeno’s Paradox, and the idea that a thing can be folded infinitely, that no two certainties, perhaps, ever meet. That nothing meets. I see this especially in the final line of “Astrolabe”: “I measure the distance home.” In some ways, this is a poetry of refusal, a refusal to come to a clean conclusion, but in others, it is a poetry of acceptance, understanding the truth of not-knowing. Perhaps this is unfair, but: which is it? Is it either?

Fludde is defined by poems which try to follow and transcribe the unexpected voice that has emerged in the act of writing, and then follow it to its inevitable ending place. This ending place was typically signaled to me by the conclusion of the poem’s metrics—to my ear, anyway. I was very careful to transcribe faithfully and enact minimal revision (the revision came more through the writing of countless similar poems—practice for the real thing, so to speak). So the book for me was an exercise, I think, in that method of listening, of acceptance of what I hear; although of course I hope it has more fulfilling resonances for a reader and doesn’t read like a procedure. As far as the book’s subjects, the refusal to come to a clean conclusion was not intentional on my part, because I didn’t feel I had as much conscious control over what I was writing and spent my time focused on the writing of lines at the ear-level, at some unconscious level. This I think is in tandem with “the truth of not-knowing.” The willingness not to know. Being receptive to the notion of not knowing. The “refusal to come to a clean conclusion,” however, implies that I know where I’m going and maybe that I’ve deliberately, willfully sought complexity—which for me is more likely to stifle poetic activity. Willfulness and poetry, I believe, don’t mix very well. Even in working with form and genre there is a form of acceptance at play—submitting to the rules, or, in the case of Fludde, submitting to an “unconscious voice.” Acceptance over refusal, therefore. One I think is capacious and generous, the other limiting. I would prefer to stay on the side of generosity.

This post may contain affiliate links.