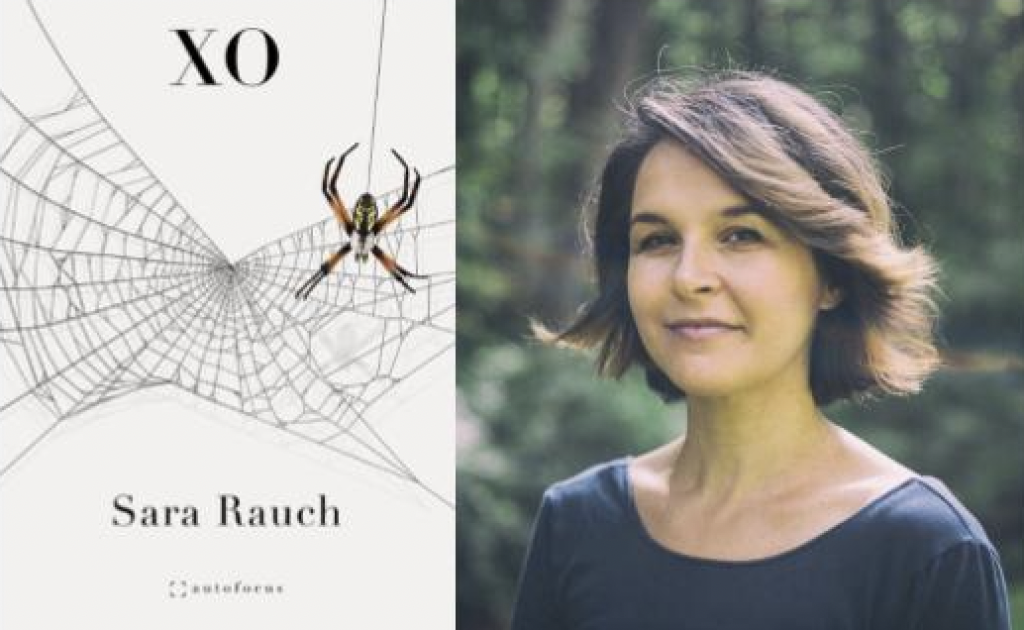

Sara Rauch’s debut short story collection, What Shines from It, won the Electric Book Award. XO, her second book, an autobiographical essay investigating mythologies of romantic love, connections to the divine, and the death/rebirth cycle, was published in spring 2022 by Autofocus. XO was the title of a short piece she published in Split Lip about the end of an affair. While in a long-term, committed relationship with another woman, she entered an affair with a married man who lived states away. XO is how he ended his break-up email to her. In the short piece XO, which became the foundation for Sara’s new book by the same title, Sara reflected:

On documents, X is how an illiterate person claims possession. Perhaps it is crude to say so, but really, what better way to mark ownership than two slashes? The clash of two lines intersecting gives life meaning. Tip the X ninety degrees and you’ve got a cross—the shape of the human body when outstretched—our entire history contained in a symbol. The X is innumerable on maps: all those crossroads, all those crashes.

X never goes it alone—maps are also riddled with O: poles, lakes, capitols, islands, their edges ever evolving. An O, no matter how imperfectly shaped, signifies a wholeness unto itself; a seed containing the entire cycle, from birth through destruction. Seeds are tenacious bastards, adapted over millennia to propagate at any cost. I think of fate this way, not as predestination but as eons-old stamina propelled by unseen forces into foreign territory. Seeds don’t give a damn whom the property belongs to.

Nearly six years after Split Lip released XO as a short piece, Sara released XO the book through a new press, Autofocus Books. I was excited to see XO finally come out. I asked Sara a series of questions about its origins and how she thinks as a writer.

How did XO come into being? Did you write various pieces separately while your larger vision for the interconnected essays was formulating? At what point did you realize that it made sense for all these pieces to come together?

XO came into being in a couple different ways. Over the course of several years immediately following the end of my long-term relationship and my affair, I wrote a bunch of essays, mainly about the affair, some lingering uncertainty over my sexuality, and the evolution of my spiritual life. A few of these essays were published but most were just foundation work. That was frustrating, sometimes, but ultimately necessary.

Then, at the very beginning of the pandemic, when we were still in lockdown in the Northeast US, my eldest cat died, I quit drinking, and this black bear showed up in my backyard one afternoon. By that point, I’d been thinking about this project for a long time, but hadn’t been able to get into it the way I knew I really needed to in order to pull it off. Honestly, a big part of me wasn’t even sure I wanted to—there’s that ever-present question of why not let sleeping ghosts lie?

Was it my cat’s death, the sobriety, the bear, or maybe some combination of all three that reoriented me toward this project? Maybe. I mean, I think so. I guess I just recognized that it was time, that I was ready, and once I could see that, I was able to set off on the path of writing the book. Much to my relief, many of the “failed” essays of prior years came in handy as I worked.

You describe your approach to writing and life as a type of collaging. Did someone teach you collaging or did you mostly learn it on your own? When did you realize that it was also your chosen approach to life?

I suspect I have an innate attraction to and understanding of patterns, and that my draw toward collaging—visually and as a writer—arises from that inborn tendency. With a collage, there’s this marvelous ability to be playful with “pieces” and puzzle out an ecosystem. It may or may not have become a conscious decision and approach to life in my teen years, when I collaged my entire bedroom with images clipped from the teenage fashion magazines so indicative of that time (lots of CK One ads and disembodied lips kissing) or when I first started writing poems that were much more clusters of images than they were narrative or maybe when I adopted a minimalist lifestyle in my early thirties and got really specific about what “fit” in my life and what plainly didn’t.

I seem to have a sort of “spatial intuition” in that I can often “see” where a thing fits. This makes rearranging a room easy, but it is sometimes hard to translate to writing—as when I’m creating the pieces it’s not always apparent to me where they will go, and I usually stumble around for a while, moving scenes and ideas. There’s very little that’s linear about the way I think, it’s almost all connective and/or relational, though I find having a language to discuss structure, like what Jane Alison breaks down in Meander, Spiral, Explode, has helped enormously. To understand a story’s structure—no matter how unusual—is like having a map.

Speaking of maps, you also like to use the concept of maps to describe your book or what you were trying to hand off to your readers. Can you say something about the role of maps?

I can say a lot of things about the role of maps! First, I’ll quote Melville in Moby-Dick: “It’s not down in any map; true places never are,” but I’ll follow that closely with this idea that maps are a very specific way of seeing the world. When I was researching the maps aspect of XO, I encountered an idea that I suppose is obvious enough but had never occurred to me, which is that maps are noted for what they include, but are as notable for what they leave out. Is there a symbolic connection there to what I was trying to do in XO? Absolutely. XO is an extremely intimate book, and it reveals plenty of hyper-personal information, but it is not an exhaustive account of the roughly eight years of time the narrative spans. I had to choose what to show the reader—what was important to the narrative—and I also had to decide what to leave out. Some of the stuff that doesn’t appear in the book is probably felt through subtext, some was simply uninteresting, and some was excluded because it is too close to my “true place” to show the rest of the world.

Is that line of thinking about what to leave in and what to leave out specific to your book overall or more in specific parts?

Both, I think. Overall, because I wanted to walk this line of vulnerability for the book, to inhabit the ambiguous space about what can be known and what can be proven, and to do that kind of thing involves a tightrope walk between what to show and what to keep hidden. But I definitely did have to walk this line a bit more carefully in specific parts, in order to protect the identities of the principal characters, and also, on a deeper emotional level, to protect my own memories of these relationships.

Memory is a funny thing, right? On some level, memories can feel like locked rooms that you might enter at will and find a moment perfect and unchanged. But, the reality is that we’re constantly rewriting our memories, even as we remember them. So those perfectly preserved rooms are shifting and changing constantly, as we are.

Do you think these thoughts on memory apply more generally to your writing?

It certainly can. I don’t always do it consciously, but very often what I write about is that unknowable, ambiguous space between: people and people, people and objects, people and nature, people and spirit. That ambiguous space is so fertile for me. I’ve never been a person who needs all the answers, or who has to understand everything—in a lot of ways, I really like not knowing. It allows for mystery, for surprise, for magic.

Some of my favorite stories in my first book, What Shines from It, are heavily autobiographical, maybe much in part because when I went into memories I was often surprised by the things I found there: those feelings, those opinions, those ideas, even those objects—I thought I knew what I wanted to say about them, and then as I was writing, something completely unexpected would rise up and change my course. There’s this constant malleability to life that can be so scary to embrace, but also, it can be a lot of fun—in a revealing way—to let yourself not know.

In some ways, are you still working on other essays that connect to your book?

I wish the answer to this question was no [laughs], but to be honest, I suspect I’ll be working on other essays connected to this piece for a while. Every writer has themes that obsess them and XO pretty much covers all of mine: love, sex, God, death, rebirth, the natural world and humans’ relationship to it, what is truth and why do we tell stories. These ideas inform everything I write, fiction or non.

More specifically, I’d say, the affair that the narrative centers around really altered the ways in which I see myself and the ways in which I interact with the world; because of that, there remain several approaches to (and from) this material that I haven’t quite been able to articulate, yet. This experience opened a door for me, and then beyond that, a (possibly infinite) hallway of doors to open.

Plus, I have this uncomfortable feeling of shifts in time and perspective. What I’ve written in XO is true, but my perspective on the matter has already changed in some ways. I think this is an inevitability, and I’m not sure how other nonfiction writers deal with this phenomenon, though I’m doing my best to sit with the reality that nothing—not even the stories I tell myself—can remain static.

Do people ever ask you point blank, “What were you thinking?” Did you ever ask that of yourself? Do you still?

As with all these questions, I think in layers of answers, as in a collage. I mean, first: I wasn’t. This was a project in which “thinking” needed to be pushed aside to get written. Instinct takes over for a while. Kind of like the affair itself, once I surrendered, everything I had went into it. I have Input and Deliberative in my top 5 Clifton Strengths, which means I give everything a lot of thought—maybe too much thought—but once I make a decision, I’m all in.

So, when I wrote the earliest draft of this book in the early days of the pandemic, what had constituted “normal” life was suspended. In a way, that gave me a kind of freedom to get this story down. Those early drafts were written just for me, because I felt like I needed to remove this series of events from my psyche and writing is how I do that. But as the manuscript developed and I revised, and then especially once I’d agreed to publish it, I had to make peace with my actions (once again).

Why was I putting this highly personal, private, moment in my life out there for the world to see? And the answers that came to me were all about freedom. Partly for myself, but partly because I wanted to contribute to the representation of bisexuality in literature. Bi-invisibility is ebbing, slowly, and it can only do so if those of us who claim the identity continue to talk about it even when we’re in heteronormative relationships, as I currently am.

I also wanted to destigmatize the reality of being “the other woman.” Culturally, when two people are involved in an affair, the other woman almost always bears more (public) shame than the man—why? The other woman is a homewrecker and a whore; she does not care for the family she tears apart; she’s selfish and amoral. I wanted to call bullshit on that stereotype: I was none of those culturally prescribed things and yet there I was, sleeping with another woman’s husband. The statistics are something like 51 percent of women have an affair at some point in their lives—but so few of us talk about it, probably because of that shame.

I recognize that my behavior (and, let’s not forget, the behavior of the man I had the affair with) is well outside the boundaries of what is considered morally acceptable. But, and this is a big BUT, I wanted to find empathy for that woman, and that man. I knew then, and I know now, that regardless of one’s decision in an impossible situation such as the one I confronted, there will be grief. Can we hold space for that truth? I tried to in XO.

What can you share about your process of creation that might be helpful to other writers who are struggling to write complex personal essays?

My best and perhaps only advice is to keep going. Be okay with making a mess, be okay with it taking a long time. The important thing is to recognize that if you’ve got a story that haunts you, it’s haunting you for a reason.

I interviewed the great writer Quintan Ana Wikswo several years back, and she said something I have not forgotten: “I am not interested in work that does not stalk or hunt me. It has to want me as much as I want it or there’s no value in the relationship.” That’s my guiding mantra these days—trusting when an instinct won’t quit and leaning into it, no matter how scary. Take your time, be patient, push hard when you can, and keep going. Trust the story; it knows what it wants to tell.

Jim Ross jumped into creative pursuits in 2015 after a rewarding research career. His publications include Bombay Gin, Columbia Journal, Hippocampus, Lunch Ticket, MAKE, Newfound, The Atlantic, and Typehouse. Representative text-based photo essays include Barren, Ilanot Review, Kestrel, Litro, New World Writing, and Sweet. Jim and family split time between Maryland and West Virginia.

This post may contain affiliate links.