[Clash Books; 2022]

In Ways of Seeing, John Berger writes, “the relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.” Mark de Silva’s bumper-sized sophomore novel, The Logos, expands on Berger’s idea, examining if it’s possible to know what we are seeing, and, more importantly, if we really want to know.

The artist and narrator of The Logos has a gift for capturing the acute essence of his subjects. He seems to see them in ways others can’t. It’s why his long-standing muse and lover left six months ago—“I hate the way you see me”—and a billionaire businessman, James Garrett, wants to employ him to help launch a range of commercial products, creating images, vastly displayed, without branding or text, on billboards across New York. Consumers will look up, unaware they are even seeing an advert. The artist agrees to the role, given that he is lovelorn and poor, and the businessman is willing to pay an unimaginably high fee. Yet the Faustian set-up of this novel does little to prepare the reader for what is in store. The internal focus and the detailed revelation of the artist’s thoughts are not depictions of a sliding moral decline or a cautionary tale of artistic compromise, but a coolly described exegesis of the artist’s environment—a portrait of the way he sees others and the world around him.

The artist’s first task, as Garrett’s client, is to sample a new smart drink, “Theria,” whilst watching a football game and a movie on his television. The drink promises to provide a lucidity of thought and the artist is encouraged to sketch while viewing. Over the course of many pages, the artist relays the specific plays on the football field, explaining tactical maneuvers and the intricacies of players’ movements. The drink appears to provide a strange illumination. One player stands out for his aggression and talent: Duke. The artist realizes, “it was Duke I was meant to see.” Likewise, one of the actors in the lengthily opined-on movie has a—perhaps Theria-induced—“gravitational pull.” Her name is Daphne. Garrett confirms Duke and Daphne are subjects specially chosen by him for the campaign. The artist must meet them, observe them, capture them in whichever way he chooses. “Your eye will always be on the two of them,” Garrett insists. “And then something happens. Or nothing happens. Or maybe something terrible unfolds.” The result will be that their images are seen all over New York City.

If a man expounding, at length, on a football game sounds off-putting for some readers—it may well be. But de Silva is not a conventional writer, and his intention is to subvert the traditional rules of plot development, pacing, and character. Or, at least to remodel them in some way. Having the artist as narrator, a cultural polymath whose thoughts are delivered in essayistic language, we gain access to a heightened interpretation of his surroundings. He is an unusual fictional narrator, less interested in himself than the observable world, detached yet loquacious. For example, he is brilliant at dissecting New York’s boroughs. Explaining, in a strangely positive yet misanthropic way, why he chose to live in the Bronx he says, “The chief virtue of this place was this sense of not belonging, of non-community, which had begun to me to seem, paradoxically, more humanistic than banding together with others in common misunderstanding.” The interiority of this artist does not consist of insecurities or the self, but the constant messaging of exterior concerns, all that he sees. And we get to see not only what he sees, but also how he sees, in all its wonderfully inflated detail.

Yet for all the artist’s intelligence and artistic genius, signs of amoral, possibly sociopathic tendencies are present throughout. His relationship with Daphne and Duke, and the resulting portraits, appear to promote uncomfortable stereotypes: young, overly-sexualized women, consensual to male violence, and Black men, atavistically violent, drawn to drugs and crime. Is this what Garrett intended? Is it why he chose Daphne and Duke? Maybe the billboards are there to reflect our own cliched prejudice, the truth of what we really see without even knowing it. Duke and Daphne don’t seem to mind; they like how the artist sees them. Perhaps it’s the Theria talking, or perhaps they see the world in the same way as everybody else and believe the artist has struck upon an essential truth of their interpreted selves. We learn that James Garrett used to own a company called JG Chemicals that specialized in dubious crowd control technology. In the cool, unadorned prose, the focus on privileged people in advertising and art, operating in a moral vacuum, there are strong echoes of another JG, this time Ballard.

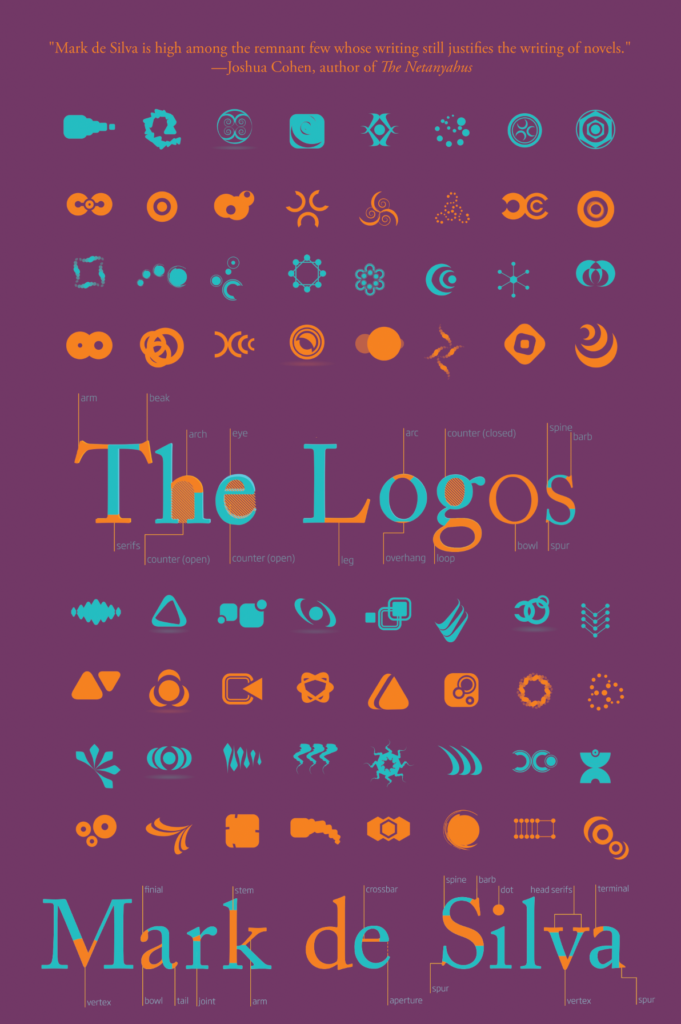

Aristotle described logos as reasoned logic. In Christian theology it’s the divine word of God. It crops up in Western philosophy, Jungian psychology, the theory of sales, advertising, branding, courtroom dispatches, speechwriting. And, of course, there’s the other sort of logos: the swish, the golden arch, the crunched apple. Over the course of de Silva’s The Logos, pinning down a definition is a slippery task; this many-tentacled novel seems to reach out to several definitions and yet, curiously, it’s the absence of logic, reason, and commercial emblems that reside at the core of this extraordinary novel. Could de Silva’s logos be meant as an expression of the divine? If so, what terrible things is God saying about us? Garrett advises the artist to, “just keep on drawing, straight through i . . . that’s how you get to the logos, right?” In the same way, you just have to keep on reading The Logos, straight through. It’s the only way you’ll ever truly know what you are seeing.

Simon Lowe is a British writer. His stories have appeared in EX/Post, Breakwater Review, AMP, Akashic Books online, Ponder Review, and elsewhere. His novel, The World is at War, Again, was published June 2021 (Elsewhen Press).

This post may contain affiliate links.