[University of Iowa Press; 2022]

Fandom: The Next Generation, a collection of sociology and media studies essays recently published by University of Iowa Press, merits a good look for a couple of reasons. Let’s start with the latter half of the title. As reboots, remakes, universe extensions, and homages populate more and more of the cultural landscape, a whole set of turf battles comes along with them, particularly those between, as the title suggests, generations. When Kate Bush’s “Running up That Hill” was featured on the new season of Stranger Things, it shot up to #1 on the charts, prompting Gen-Xers to puff out their chests and claim a little cultural credibility with Zoomers, who, presumably like Nietzsche’s last man, blinked in serene indifference. Several essays in the collection take on these generational complexities: for example, how to pass on one’s fandom in Dr. Who or Star Wars to your children, or “what happens when boys and girls grow up and remain fans?” as in one essay which examines a cohort of Dutch women attending Backstreet Boys reunion concerts in the mid-2010s.

But to my mind, the more compelling reason to dive into the academic subfield of “fan studies” is to think long and hard about this particular subject position. There are several ways that one might address the topic of fandom that are worth laying out before getting into the contents of the book:

- Questions of Motivation: Quite literally, what moves us to act in the world (whether purchasing a ticket, posting on a message board, writing fan fiction, or mobilizing resources and moving people to put on a convention or stage an event).

- Questions of Alienation: How can fandom help us understand the twin motors of alienation: mediated (or more accurately, mediatized) experience in a consumer, spectacle-centered society, and the disempowerment built in at the structural level in our economy and politics, where the sphere of meaningful action is quite small, even though we can spout off about things with others in ways we could not have before.

- Questions of Freedom and Identity: Fandom, typically expressed through the formation of small communities of mutual interest, seems to be the paradigmatic case of voluntary activity. This is the post-Enlightenment, liberal subject that presumes fandom, unlike some other identity category (race, gender, class, etc.), is not structuring of your worldview, but a realm of pure freedom. But can fandom become the anchor of identity and the lens through which world events are processed? Any fans of the sprawling, world-building comedy projects of On Cinema at the Cinema or Alan Partridge cannot dislodge the mind worms that make it basically impossible to process certain realities (the derangement of American and British culture in the wake of imperial decline, respectively) without recourse to them.

- Phenomenological Questions: Our investments in cultural products can be an index to locate ourselves not just in time (or “the life-course,” in the sociological parlance of several essays in the book), but in what the great Marxist cultural theorist Raymond Williams called a “structure of feeling.” “It is perhaps only in art—and this is the importance of art—” Williams writes in The Long Revolution, “that it can be realized, and communicated, as a whole experience.” When fans comment on the uncanny effects of aging in an X-Files or Twin Peaks reboot, they are contending with, as we might now say, that originary vibe that drew them into two very vibey shows.

I raise these lenses not to engage in the pedantic exercise of criticizing a book for failing to be a different kind of book. It is very clear and much to the credit of editors Bridget Kies and Megan Connor that this collection is focused on expressions of fandom from fans themselves, and most of the methodological choices—culling Tweets and Reddit posts, conducting online surveys and focus groups, surveying fan fiction, leading semi-structured interviews —serve this end over more speculative or critical approaches. Moreover, given the subject matter, it is unsurprising that many of these contributions are clearly passion projects—what the contributors might call “auto-ethnography,” though I’ve always preferred my anthropologist friend’s term, “me-search.”

However, in reading through the collection, I couldn’t help but think that, responsible as this approach may be for practitioners of sociology, media studies, or associated social sciences, it doesn’t yield the most profound insights on the nature of fandom today. The collection is divided into three sections: “Reboots, Revivals and Nostalgia,” “Generations of Enduring Fandoms,” and “Generational Tensions.” The selection of fan communities includes those you would expect (Star Wars, Tolkien, Jane Austen, The X-Files, Sherlock Holmes) and a few you might not (the Turkish actress Türkan Şoray or The Man From U.N.C.L.E.), but does not stray from mainstream cultural products. This has the consequence of unfolding the logic of and reacting to decisions made in production companies and marketing boardrooms (e.g. to make reboots more sensitive to identity politics), which locks discussions into pretty predictable patterns. As one essay on The X-Files puts it, “that nostalgia for a beloved show competes with progressive attitudes towards gender representation . . . raises questions for how we deal with being fans of problematic things.” That nostalgia and politics (or emotional and rational attachments) often work at cross-purposes is fairly obvious. What remains unremarked upon is that certain classes of people are consuming tremendous amounts of media, and more and more of that is recycled or reconfigured narrative content. One can extend David Harvey’s remark that “the dream of Silicon Valley is to give us all a universal basic income so we can sit on a couch and just binge-watch on Netflix” to include the act of talking about and refining our responses to these cultural objects placed before us (perhaps even using the conceptual tools we’ve learned in media studies and sociology classes).

This is to say that I’m not convinced that fans themselves, when filtered through the instruments of these academic disciplines, are the most articulate or insightful commenters on fandom. For example, one essay on the Lizzie Bennet Diaries, a web series updating Pride and Prejudice, notes how contemporary issues like student loan debt were worked in to, in the words of one fan, make it “a bit easier to relate” and “[add] depth to the original character [in Pride and Prejudice] and [her] choices.” This leads another fan to make the following comment: “Taking a job that might not be your dream in order to afford taking care of yourself and your family is absolutely something people can relate to today.” In this regard, it would have been nice for contributors to seize the reins and take some grand, albeit academically irresponsible, swings at interpreting the inter- and multi-generational fan cultures they engage, instead of falling back on the sociological practice of over-categorization or remaining within the comfortable idiom of identity politics.

But in another sense, I understand and commend the fan-centered focus of this book, because, to the first and second lenses laid out above, it is entirely rational to immerse oneself in fandom as one of the few spaces where meaningful agency, community, and creative self-expression can emerge. Two noticeable exclusions from this collection are sports and, aside from the Backstreet Boys essay, music. In these venerable bastions of fandom, we can see all kinds of interesting things emerging, also tracking this theme of generations. Here in Philadelphia, a baseline feature of civic identity involves your relationship with our sports teams, but this manifests quite differently depending on your route and level of investment, leading to beautiful new communities like weird twitter, vaguely communist, “slop” fiend Sixers fans, alongside the old guard you find at the bar and occasionally showing up on Action News. Or in the realm of music, you can look at something like Jokermen, a podcast-cum-durational art project by two thirty-somethings that originally probed every dimension of late period Bob Dylan, expanded into his whole catalogue, and is now doing the same for John Cale and Lou Reed. In these and countless other cases, the “irrational” levels of investment that we often associate with fandom provides the anchor to do interesting things and synthesize parts of our increasingly fragmentary day-to-day experience.

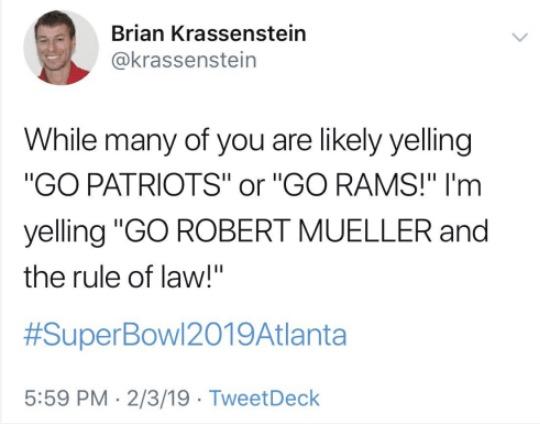

There is a political dimension to some of the essays in Fandom: The Next Generation, especially the politics of representation and gender politics. This is shown most clearly in the chapters which bookend the collection, the first of which looks at the fractious online discussions of reboots (which, like so much of the Internet, draws in reactionary and retrograde views on gender) and the final which deals with policing the boundaries of fandom by level of investment. But again, there seems to be a broader dimension that is left unexplored here, which is that, for many people, politics itself has transformed into a realm of fandom as the possibilities for impactful civic action vanish. The Trump era produced no shortage of derangements, including “reply guys” like the Krassenstein brothers, who produced the perfect expression of politics as fandom.

Sadly, you can see the same phenomenon spreading to how people relate to war, at least if you probe the online spaces that constitute much of the data for essays of the sort that appear in this volume. All this is to say that fandom is an incredibly rich prism through which to reflect on questions of agency, identity, and indeed intergenerational relations. I’m less convinced that media studies and the social sciences are the fora to explore such questions, though maybe there is a subfield that can supplement “fan studies” and satisfy my own (I will admit, ultimately pedantic) predilections and fannish desires.

Michael Schapira is an Interviews Editor at Full Stop.

This post may contain affiliate links.