This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

When the pseudonymous Spanish author Carmen Mola won the prestigious Planeta literary prize in October 2021, three men came forward to accept the prize and the one-million euro award that went with it. Until this moment, the identity of the author was unknown. Most assumed Mola was a woman, even dubbing “her” Spain’s Elena Ferrante, in reference to another very publicly private writer who famously finds refuge in anonymity.

In a 2019 op-ed, Ferrante called for a need to save a planet on the edge of catastrophe. To do so, she urged women to reclaim systems of power, including writing: “The female story, told with increasing skill, increasingly widespread and unapologetic, is what must now assume power.” When the three men walked on stage, it became clear that they understood Ferrante’s call to include them. That they could tell the female story for women. They created a false identity for Mola, and on their website called her a married, female professor in Madrid. Their detective novels feature an eccentric female police inspector as the protagonist, centering a woman in a traditionally male genre. They capitalized on the growing number of people interested in reading diverse voices and hid behind a woman’s name, bringing to the foreground the presumption and fragility of the male ego in the face of a changed literary landscape. In short, they failed to understand the true value Ferrante adds to the literary canon.

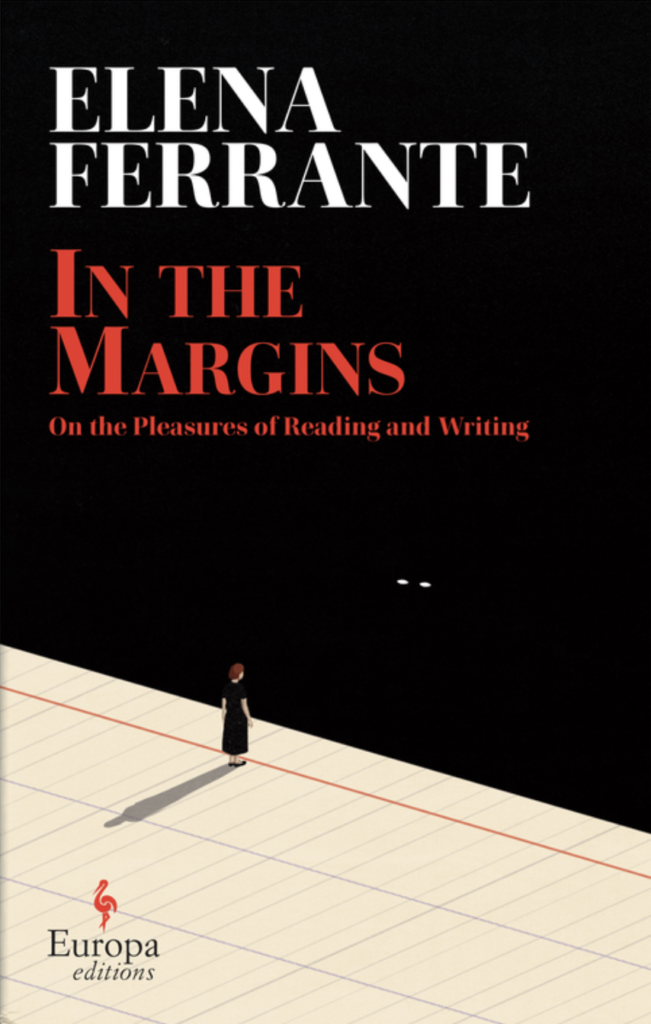

Despite not being a public face, Ferrante often weighs in on the status of the woman author via op-eds or written interviews. She’s written eight novels, one children’s book, and two nonfiction books. Her first work of nonfiction, Frantumaglia (2016), offered an intimate self-portrait of a successful writer: her highs and lows of writing stories and responding to interview questions, her thoughts as her novels get adapted into films, and her relationship to psychoanalysis and motherhood. Her latest book, In the Margins (March 2022), takes us back in time. In it, Ferrante lends insight into the formation of its author as a reader and writer, as well as the power she gains from her insistence on remaining pseudonymous. Over the course of four essays, Ferrante discusses the woman writer’s need to balance coherence with disorder, her sometimes paralyzing dedication to realism, the female “I,” and the shortcomings of Dante’s Commedia. Throughout, she shares anecdotes from before her career took off, back when doubt marred her projects and she thought nothing she wrote could equal the books she liked, “maybe because [she] was a woman and therefore sentimental.”

In the Margins is the origin story of a woman who learned to write in the margins—a stand-in for the cage of androcentric writing—before incorporating a convulsive type of writing: a style that, in short, allowed her to push the limits of what we consider the female story to be. A close look at two of its essays, “Histories, I” and “Aquamarine,” reveals that writing beyond the margins is necessary not just to reclaim a system of power, but to expose how telling the female story with honesty requires new techniques of language. To defy literary conventions is to engage in modern-day witchcraft.

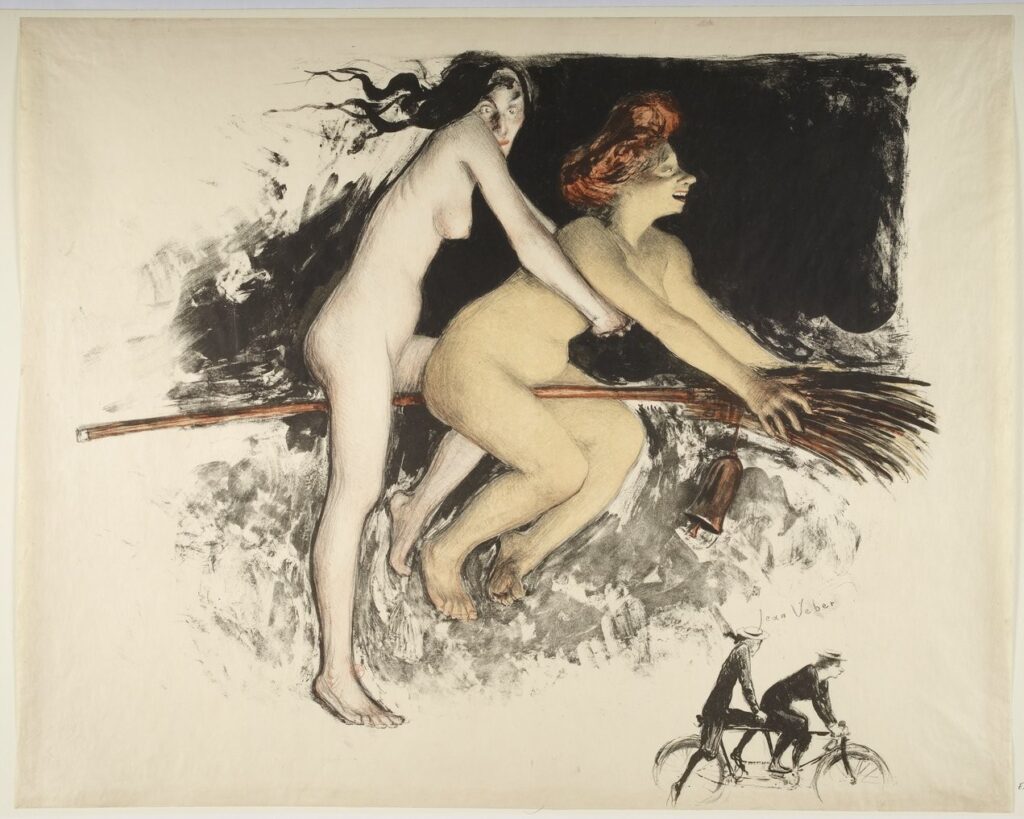

In “Histories, I,” Ferrante, like many great women artists before her, uses the figure of the witch to demonstrate writing’s ability to subvert the status quo. She opens the essay by dissecting Emily Dickinson’s four-line poem “Witchcraft was hung, in History”:

Witchcraft was hung, in History,

But History and I

Find all the Witchcraft that we need

Around us, every Day—

Dickinson’s reference to the presence of witchcraft today (“Around us, every Day”) led Ferrante to fantasize how “a female ‘I’ would derive a writing that, as needed, would return to complete [spellwork] in daily life, joining people and things that supposedly couldn’t be joined.” Writing, then, allows Ferrante to do two things: revive a form of spellwork supposedly relegated to the past, and align herself with a history of (primarily) women living on the margins of society.

Between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe, witches became ossified as the devil’s agent in sewing chaos and were blamed for everything: Illness, infertility, death, disease, and community conflict all became the witch’s doing. Kristen Sollée details this history in her essay “Transmutation of the Witch” from Taschen’s Witchcraft volume in their The Library of Esoterica series. According to Sollée, women were prosecuted en masse as the Catholic Church feared and sought to root out a demonic presence in the world. When Heinrich Kramer published Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches) in 1487, his text became famous for its assertion that “all witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable.” The invention of the printing press circa 1450 allowed Malleus Maleficarum and other witch-hunting tracts to be disseminated to the masses. The earliest mass-produced writing, then, was used to create guidebooks on how to identify and hunt down women deemed a danger to society.

As highlighted in Sollée’s essay, the first text sympathetic to witches didn’t come until 1862, when Jules Michelet published La Sorcière. His book details how the witch was a figure created by the Catholic Church and used against any gifted healer or “priestess of nature.” Though he incorrectly states that all women accused of witchcraft were herbalists (they were generally poor and older, though not united by any trade), his prose captured the attention of a readership interested in understanding the witch as a woman figure persecuted for her knowledge beyond the margins of the patriarchy. “Under a system of such blind repression,” Michelet says, “there was just the same risk in daring little as in daring much. Daring itself made people bolder; and the Witch was able to dare anything.” He refigured the sorceress as someone shunned from public life, continuing to distribute her knowledge in private and emboldened by the risk incurred in doing so. In “Histories, I,” Ferrante imagines Dickinson writing her poem as a challenge to this persecution, “almost a confrontation.”

The transfiguration of slurs into words of honor is something oppressed groups have done throughout history to reinforce their own agency. In the 1960s and 70s, the witch became a symbol of resistance for legions of feminist activists. Today, the witch is both a marginalized historical figure (“hung, in History”) and a symbol of female autonomy. And in Ferrante’s imagination, the witch’s resistance takes the form of a modern woman: “I saw her, brow furrowed, gaze intense, writing on the computer in an apartment in Turin, trying to invent other women, mothers, sisters, friends—a witch friend—and places in Naples.” Reflecting on the witch’s potential to become an author, Ferrante writes, “I felt she was true, with a truth that had to do with me.” For Ferrante, as for Dickinson and countless other activists, witchcraft has changed in its form if not in its end goal, and they transfigured wands into pens.

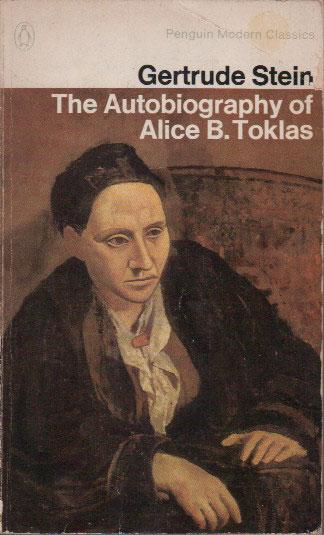

“Histories, I” uses Dickinson’s poem only as the starting point in a greater discourse that posits feminine writing as an act that mirrors the alchemy of witchcraft. Ferrante turns the conversation to a criticism Gertrude Stein once had of Hemingway: that his books included so-called “confessions” offering not an honest portrait of himself, but “a literary product that is well made, successful, but false for opportunistic reasons.” (A critique that brings to mind the forced “confessions” of alleged witches, which were understood as unquestionable truths despite their obvious incentive to lie.) Stein charges him with writing not the truth, but a distorted self-portrait designed to advance his career.

Ferrante asks: How, then, did Stein write about the “real” Gertrude, in contrast to Hemingway’s false self-portrait? She suggests that Stein achieved this with The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. It’s a book that deforms conventional structure by writing her lifelong partner’s autobiography (not biography) and focusing largely on herself, that is, Gertrude Stein. Ferrante argues that this book allows Stein to demonstrate that writing a true story about the self is not so much about writing truthfully as much as “applying force to the great containers of literary writing.” Stein demonstrates the necessity of dismantling forms that seem “most comfortable, most beautiful, and instead are a death trap for our intention to write ‘truthfully.’” By playing with the bounds of memoir, Stein exposes how language and form aren’t universally suitable for truth-telling. “That is her differentness, and maybe Dickinson would say: that is her skill as a witch,” Ferrante says. She invokes witchcraft because it is a form of alchemy, a guidebook for combining what already exists in nature to create something wholly new. This is what Stein did with Autobiography: She mixed a new ingredient into the black cauldron of writing and broke free from the limiting expectation of nonfiction.

Ferrante ends “Histories, I” by reflecting on the lack of collaboration between her protagonists in the Neapolitan Quartet. Though the clash between Elena and Lila’s writing is the thread that ties the story together, and though as children the two girls dreamt of writing a book together, Ferrante never lets her protagonists enter into this collaboration. “An ending like that was inconceivable,” Ferrante says. The point of the Quartet was to show that the two friends were wrong to believe they could pursue writing alone. Now, reflecting on Dickinson’s poem, she sees that it generates another space: “around us.” Ferrante believes these words hold the next step for literature written by women: to “fuse our talents” “against the bad language that historically doesn’t provide a welcome for our truth.” She urges, in other words, for women not only to write but to collaborate in their writing. It is an idea reminiscent of the importance of the coven, where witches convene to freely share their beliefs and combine their energy to supercharge results, a practice that creates stronger and more liberated members.

To be able to envision new paths for writing—that, Ferrante says, is a woman author’s skill as a witch. And what, then, has Ferrante herself done to bend the cage of writing with her own witch power? That lies in her choice to remain pseudonymous for more than thirty years.

In the essay “Aquamarine,” Ferrante shares her struggles as a young writer. In her early stories, she wanted to create an “exact reproduction of reality,” a desire that led her to agonize over realism and studiously practice descriptions. She dedicates a page and a half of “Aquamarine” to her failure to describe a ring her mother once wore: In her mind, the ring was variable, and she couldn’t capture its specificity in dialect or Italian, though she toyed with “sky-blue light,” “pale celestial light,” “pale celestial aquamarine,” and “cyanotic aquamarine” as descriptors. No matter what she wrote, the words remained a false shadow of the object. Yet telling the truth as best she can remains, Ferrante says, her aesthetic imperative (it’s no wonder she loved Stein’s Autobiography).

Eventually, she became consoled by Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist and His Master, which taught her that “the teller is always a distorting mirror.” She learned to become less exacting, to do only her best to speak truthfully. She even wrote a book and found she wanted to send it to a publisher. But then, again, she ran into the trouble of telling the truth in her cover letter. She spent pages explaining how the story came about, “what real persons and events had nourished it,” the tradition she wrote in, her favorite novels, and how her story distorted her real life. “And yet the more I immersed myself in the subject, the more complicated the truth of the cover letter became,” Ferrante says. Eventually, she abandoned the attempt to publish and let years pass without querying.

The failure of the cover letter gave her a new idea: to write as her female narrators, to develop first-person stories from their subjective writing. She used this form for her first three novels: Troubling Love (1992), The Days of Abandonment (2002), and The Lost Daughter (2006). These books started with a “female first person who . . . has been able to upset the solidity of the chessboard on which she was castled.” She wrote herself out of paralysis by beginning with the cage of consistency, an established world, and facts of reality. Then she wrote over this orderly scaffolding with “convulsive, disintegrating” writing, filled with oxymorons, inconsistencies, contradictions, fusing bodies, and ordinary objects turned lethal. “Both kinds of writing are mine and, at the same time, Delia’s, Olga’s, Leda’s . . . I am, I would say, their autobiography as they are mine.” Here, she did something akin to Stein: She broke free of the margins by bringing herself so close to her protagonists as to be interchangeable with them.

What remains her most notable instance of witchcraft was her decision to remove the “me” from her writing. By publishing under a pseudonym, she no longer had to be true to her experience. “Trying to tell the thing as it is can become paralyzing,” she admits. Now, she doesn’t have to. Thanks to her anonymity, her books are free to take on a life of their own. She avoids the question of realism because the stories belong wholly to her characters.

It also means there are no tell-all Ferrante biographies, page six spreads on what she wears or who she dates, or Globe photos outraged by her aging face. Just consider the treatment of Eve Babitz or Princess Diana, whose lives were reduced to stories in tabloids that emphasized their various romantic entanglements. In this way, Ferrante has cast a spell that allows her to retain complete control over her public image—and demonstrates that other female authors deserve the same respect. By preserving her pseudonym, Ferrante insists the female story should be regarded as worthy of political and philosophical conversation.

And it’s working: take The Atlantic’s review of The Lying Life of Adults (2020), which uses Ferrante’s own theory of fiction from Frantumaglia (2016) to analyze her then-latest novel. Or James Wood’s 2013 New Yorker essay on Ferrante’s oeuvre, the first mainstream English-language coverage of her work. “She seems to enjoy the psychic surplus, the outrageousness, the terrible, singular complexity of her protagonists’ familial dramas,” Wood said. He dubbed her willingness to attack themes of motherhood and womanhood “post-ideological savagery.” At the same time, the “Ferrante effect” has been defined as a phenomenon that has shaken the male-dominated literary establishment by giving Italian women authors wider recognition. Italian women are winning prizes, appearing on bestseller lists, and being reviewed by establishment critics.

In the words of Ottessa Moshfegh, by masking one’s peculiarities, one invokes authority. Since Ferrante’s art, adamantly female, refuses to be identical to the male experience, theinability to discredit her with gossip about her personal life makes her doubly dangerous, doubly intractable as a prominent woman author. She’s not just a woman, but a witch.

The witch is the woman writer, is Emily Dickinson, is Gertrude Stein, is Elena Ferrante, is even Lila Cerullo of the Neapolitan Quartet, who uses her power pointedly: Like Stein, she makes a name for herself by disrupting established (male) games and bending them to her purpose (I think of how Lila eliminates her body from her wedding photograph before hanging the shredded image on the wall as art). All of them summon the witch’s magical unruliness to produce something destabilizing that “makes space for [her] whole body” in the literary canon. It is reminiscent of Hélène Cixous, who urged women to unearth l’écriture feminine (feminine writing, or reimagining language to accommodate the feminine) in order to return to their bodies.

Still, Ferrante’s greatest spell lies in getting to a deeper truth of the female story by liberating her text from her private life. She’s published more than twenty million copies worldwide, been translated into more than forty-five languages, and made bestsellers lists in a dozen countries. Because Ferrante doesn’t claim these stories to be reproductions of her real life, we must read them as representing a female experience that resonates with an international audience, and not shadows of her own divorce, motherhood, or career. To quote the occultist Aleister Crowley, if magic is “the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with the Will,” then acts of protest and resistance are acts of magic.

Ferrante’s readers are inadvertently part of a writer’s support group, a religious cult that could be called the Ferrante coven. And since covens conduct spells in circles, each member’s magic is needed and valued equally. The coven is not only a ritual meeting of practicing witches—it is an aspirational design for the literary establishment. The Ferrante coven restores a matriarchal way of art, recognizing that telling the female story as truthfully as possible is a sacred reclamation of power. That is Ferrante’s witchcraft. That is how she dissolves the margins.

Brianna Di Monda is a contributing editor for Cleveland Review of Books. Her fiction and criticism have appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, Taco Bell Quarterly, and Worms Magazine, among others.

This post may contain affiliate links.