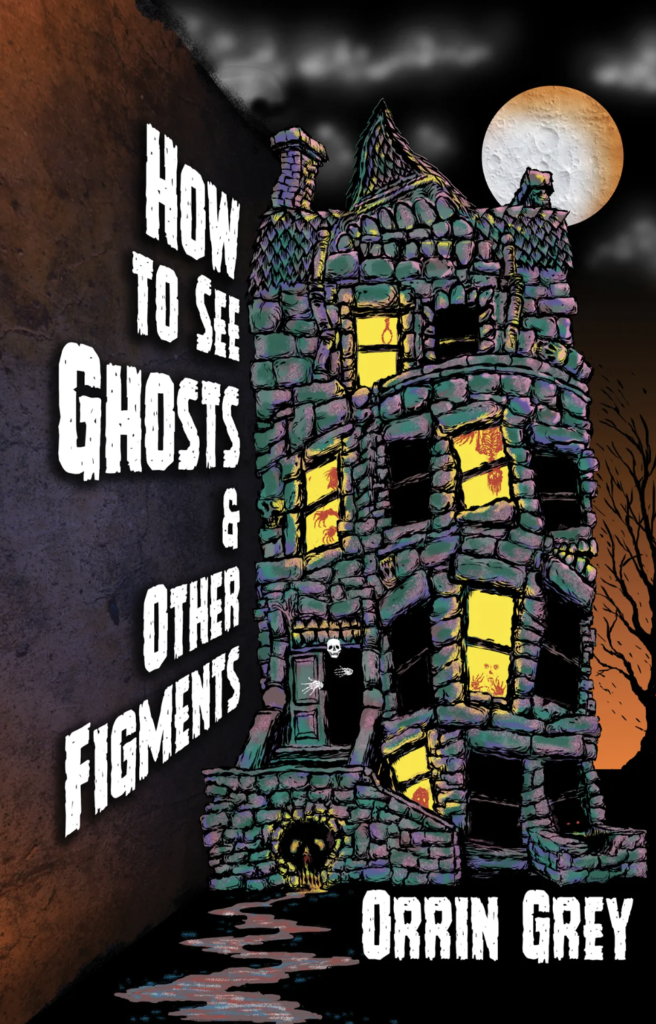

[Word Horde; 2022]

Horror literature, a narrative that lacks the benefit of images or a cast of actors, has an advantage that other types of frightful storytelling simply lack: It projects itself right into the site where terror happens. It may be obvious that horror is intended to drive fear, a primal emotional response we spend most of our lives trying (unsuccessfully) to negotiate. That fear is responsive, it is how we react to stimuli, it says almost nothing about what is outside of us. I can be terrified by a slow creak emerging from below my bed seconds before drifting off to sleep, but I am even more horrified by the quiet seconds after I tell my wife I love her and before she responds. The horror itself happens inside our minds as we think through our lives, struggle to make anything approaching a rational decision, and attempt to anticipate the consequences.

It seems a bit ironic that this is what comes to mind when reading the most recent book by Orrin Grey, because he is a near historian of the horror genre as a cultural institution, not just as a trigger for our cognitive panic. Grey’s work speaks to my own obsession with B-horror films, comic books and monster movies, Old Hollywood and classic genre motifs. It is with his newest collection from Word Horde, How to See Ghosts & Other Figments, that fans of Grey will see his biggest step forward to date, even beyond the monsters that color his earlier work.

What’s interesting about a number of stories in this new collection is that they lack what Grey describes as the “fantastical” or as something that is beyond our material world: There may be nothing supernatural going on at all in their pages. The book’s namesake is one of these, where the phantasm is more in how we see ourselves, or more specifically in how we mistake ourselves. It grapples with how the stranger we become in the mirror as we age, change, and often fail our own expectations. The characters’ emotional lives are the center of this story, particularly their reflections on loss and their grieving process, which are perhaps the pitch-perfect mental state for a haunting. You still get some classic Grey in these pages, particularly “Aum’s Fire (1987) — Annotated,” which describes an unmade movie inspired by the work of Italian filmmaker Lucio Fulci. The story takes a format that frankly shouldn’t work (academically recounting and critiquing a film that doesn’t exist) but seems to simply by virtue of Grey’s imaginative chops and bursting energy.

“The Cult and the Canary” is a great ode to Robert Chambers’s The King in Yellow, a nearly forgotten book for anyone outside of the “New Lovecraftian” scene, but a deep well for us nerds with a penchant for the Weird. The strangeness of Chambers’s work, particularly the story of a piece of art so potent that it can bring about madness, continues to have legs here, particularly in the classic party setting of gothic extravagance. “Old Haunts” is a great spin on the Cthulhu mythos, again with Grey’s complex descriptive quality: This time a haunted house is run by occultists and experienced by the strangest kind of enthusiast. “The Robot Apeman Waits for the Nightmare Blood to Stop” takes a similar approach, adopting the complex magic at the heart of cult film and the persistent drive to give in to a life less ordinary, even when its virtue is paired with suffering. “The Drunkard’s Dream” also achieves formal complexity in building a story about a grieving widower around an arcane (yet expertly crafted) old generation arcade game that strangely mirrors the inner life of our character. In these cases, there is an externalization of the inside processes, a sort of strangeness in the character’s lives that allows them the serendipity of self-reexamination. Horror is itself an externalized narrative of our obsession with escaping suffering, forming a fine line with the sadness of tragedy. Perhaps the strange arcade game provides the transfer from mourning to frightful storytelling, a way of recapturing grief and providing the emotional distance necessary to process. If only we could create video games for every great heartbreak of our life.

In Grey’s work, the world of genre, mass media, and entertainment is the outward projection of our inner turmoil. The two meld into the one, as if we exist in a self-replicating cycle of archetypes, constantly rebuilding monsters and heroes in an effort to fix what we see as hopelessly broken in our lives. This is part of why Grey’s stories build on the pantheon of “b horror” because they play a similarly universal role by creating figures with simple, yet relatable, identities, ones that most people know and can connect with. This is certainly true of Grey’s earlier collection from Word Horde, Painted Monsters & Other Strange Beasts, which relied even more heavily on the American mythology of performative horror.

There is enough here to attract Grey’s core audience, but they will be treated to a deeply emotional journey through the distant ghosts that haunt most of us. Horror itself is a vessel, a spell of types, that should create enough of a dissonance in the reader to let ideas through that might be difficult to access without that fragmentation. This acknowledgement has led to the coining of the insulting term “elevated horror” in recent years to signify horror film and literature that runs deeper in social and personal commentary, as if that wasn’t always the function of genre.

Grey is one of the best examples of this genre’s literary scene, particularly since his obsessions lend an almost encyclopedic knowledge of film, nostalgia, and kitsch. When I think of the world of horror, I think of Grey’s world. But his centrality only reinforces the fact that horror is here to help us process our own crisis, the everyday kinds of terror that belie our friendships, loves, and dwindling hours on this earth. Grey’s work is doing exactly what good horror should do: It delivers a monstrous punch right where it needs to so genre faithfuls will be satisfied, and it pushes right where we hope we will be challenged. In this way, he is cementing himself as a genre staple precisely because he checks all the boxes necessary, ensuring that no horror trope arrives simply for exploitation and enticement but are all a path to something deeper. Grey does the work we need him to do, so maybe we can sit with ourselves without all the fear his characters themselves were forced to overcome.

Shane Burley is a writer and filmmaker based in Portland, Oregon. He is the author of Why We Fight: Essays on Fascism, Resistance, and Surviving the Apocalypse (AK Press, 2021) and Fascism Today: What It Is and How to End It (AK Press, 2017), and the editor of No Pasaran: Antifascist Dispatches from a World in Crisis (AK Press, 2022). His work has been featured in places such as NBC News, Al Jazeera, Jewish Currents, The Daily Beast, The Independent, The Baffler, Bandcamp Daily, and the Oregon Historical Quarterly. He is currently co-authoring a book on antisemitism and co-editing an anthology of solarpunk speculative fiction. You can follow him on Twitter @shane_burley1 and on Instagram @shaneburley.

This post may contain affiliate links.