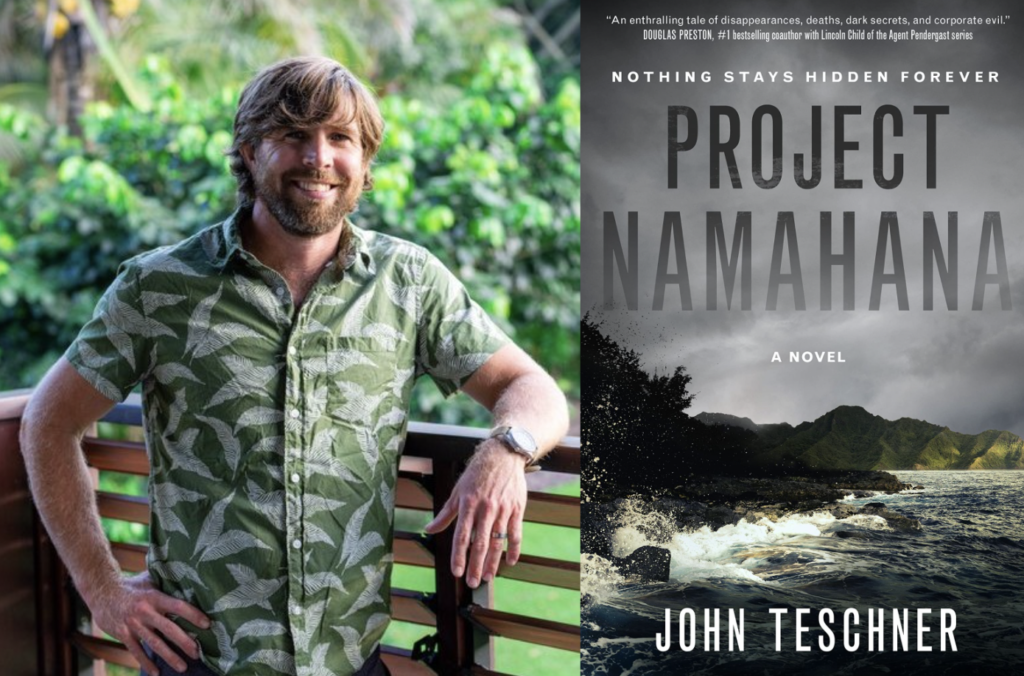

John Teschner’s debut novel, Project Namahana (Forge Books), is that rare thing: a taut, beautifully written page-turner. The story is an eco-thriller set mostly on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, where Teschner lived for seven years. In the poignant opening pages, two young boys turn up dead while swimming in a stream.

With each step, Jonah expected to see the boys emerge from the trees, wet shorts clinging to skinny thighs. Gradually, expectation was replaced by something else. It wasn’t fear—the boys had been raised in the old style: there was nothing on the island they approached without humility—just an absence, or an ebbing. The world’s comforting predictability steadily drained until he sensed every flicker and rustle of the forest with the hollow precision he felt in the final moments of a boar hunt or in the glassy hissing stillness of a wave about to close above him.

A Monsanto-like company called Benevoment seems to be the culprit. The body count rises. Micah Bernt, a burnt-out Army veteran living (if you can call it that) on Kauai, investigates the deaths, eventually getting a clutch assist from an unlikely ally.

Teschner honed Project Namahana over the course of five years, with three spent writing the first draft, and another two cutting that draft in half. “The first thing my agent said to me on our first phone call,” he told me, laughing, “was, ‘Your manuscript is 140,000 words. The typical debut novel is 80,000 words.’”

The resulting book, which clocks in at a brisk 286 pages, is lean and lush, propulsive and cerebral. Teschner is as adept at delving into a character’s psychology as he is at creating a tense, believable fight scene, or a good old-fashioned shootout. Even better, the often-grave tone is periodically punctured by moments of subtle or dry humor—as when a character asks Bernt, a quite violent man, if he ever gets angry, and Bernt replies simply, “Yes.”

The scenes on Kauai are particularly vivid and evocative, revealing a Hawaiian culture and language (pidgin) that many readers may have never encountered in popular culture. In addition to his firsthand experience on the island, Teschner is also equipped with a journalism background and an affinity for dogged research.

We talked about getting Hawaii right, challenging readers, and his budding garage envy.

(This conversation has been edited and condensed.)

Evan Allgood: Why did you decide to write this book?

John Teschner: When I was on Kauai, I had this dream that I was working on a bike in my garage—I didn’t even have a garage—and all the sudden I was surrounded by federal agents. They told me that I was irradiated with some kind of radioactive material, and they thought I’d been building a bomb, and they took me in to interrogate me. A lot of my favorite movies are really entertaining, well-done thrillers like The Bourne Identity and Michael Clayton. The dream was like that—it was like I was in a movie. I woke up and thought: I need to write a novel like that. What am I doing? Why am I writing these weird essays? I wanted to write something that an agent would be more likely to take.

Then I put together these different experiences I’ve had on Kauai, and different things that I’ve seen. There’s a real journalistic element to it, where I wanted to portray a side of life on Kauai that most people don’t see. Even a lot of haoles, white people who come over, they live there for years and never engage with a lot of that stuff. They stay in their bubble and don’t really want to see or deal with it. In our case, my wife Liz worked in an elementary school, so she saw a lot of just ordinary life. Then we joined an outrigger canoe club and made most of our friends through that, and were able to participate in the local community in a way that, unfortunately, a lot of white people don’t.

In general, I have a problem with writing that feels like it’s preaching to the choir. All kinds of writing, whatever it is, you almost never have a chance to talk to someone who doesn’t already agree with you, or to present a case to someone that isn’t going to agree with what you have to say. So I wanted to see how much I could smuggle into this novel that isn’t necessarily aimed at the kind of readers I’m used to, like my friends or the broader literary community.

How did you make sure that you got the Hawaiian pidgin language right? And why did you decide not to include a glossary or footnotes where you define those terms? I understood most of it through context and repetition, and I really liked engaging with this language that I didn’t even know existed prior to reading the book.

I had several local people who speak pidgin read it and give me feedback on it, then the publisher hired an academic at the University of Hawaii to read it over. That was one of my biggest hesitancies, and it goes toward the larger hesitancy of just being a white person writing about all these different people with different backgrounds and cultures, especially not even being from Hawaii, where that is definitely a fraught thing to do, for good reason. I wanted to get it right primarily so that my people in Hawaii would read it and think that it was true and authentic.

I never questioned that I would include pidgin because that’s how people talk. It was important to me. Hawaiian pidgin is fascinating, and kind of hilarious, and it’s really cool. The pidgin in my book is a little simplified because the language is so complex. Younger people speak it differently. People on different islands have different ways they speak it. Some people speak it very thickly, while some people code-switch in and out. I tried to keep it accessible and a little bit simplified for an audience that wasn’t familiar with it.

I’m working on another novel with some of the same characters, and I think for this next one, I will include a glossary. That was the biggest criticism that I got from some of my family members and other people who read the book, that it kind of took them out of the novel. People said, “I felt like I had to look that word up.” I really made an effort to make it understandable through context, to the degree that you need to understand it. But trying to figure that out was really tough.

One thing that I would recommend is the audio version of the novel. We made sure to get someone that spoke pidgin fluently, and I think he did a great job on it. I’d recommend people who like audio books to listen to it, because when you actually hear it, it flows even better.

You were talking before about showing people a side of Hawaii that they haven’t seen before. One thing that surprised me was how much it reminded me of parts of the South: these small, tight-knit communities where everyone’s got a gun, and they like to sit on the porch shooting the shit. Was that a parallel you noticed when you moved to Hawaii, having lived in Virginia and Georgia?

I noticed more parallels to Kenya, where I was a Peace Corps volunteer for two years. You can visit this old sugarcane plantation house in Kauai that’s uncannily similar to these tea plantation houses that the British built around the same time in Kenya. The difference is that Kenya is no longer colonized.

I totally see what you’re saying about the South, though. Hawaiians are really redneck, with the pig-hunting, fishing, all that stuff. One thing I really liked about life in Hawaii is that there’s more of a healthy convergence there. There’s less breakdown—like at least half of the people in our canoe club didn’t have college degrees, they were tradesmen, and it’s so rare to have a group of people here in the mainland that isn’t homogenous. What I’ve found in the mainland that’s so dispiriting is that, when people go out in nature, there’s almost a class and political divide. If you’re one kind of class, you’re riding dirt bikes and snowmobiles and jet skis, and if you’re wealthier or more liberal, you’re skiing or canoeing.

But I love that culture you’re describing of just sitting around drinking beer and talking and getting out of the sun. That’s a culture that I greatly appreciate, and it was one of the things that I was worried about leaving behind when we moved back to Minnesota. Fortunately I live in a neighborhood where people are pretty community-minded. Here it’s guys drinking in their garages. I have major garage envy because my garage is too small for that. (Laughs.)

Income has something to do with it in the sense that when the houses get to be a certain size, and the yards are big and everything is spread out, you don’t see people with chairs in their garages or in their driveways, where people are going to come join them. You see it in Kenya, you see it in Nairobi when you go to wealthier neighborhoods, people have giant fences. You see it in Hawaii, where all the sudden you’re in these communities where there isn’t that same relaxed atmosphere.

I have these contrasting descriptions in the book. One of them is driving through this pretty typical neighborhood in Kapaʻa, which is a big residential area, and I describe how nearly every house—and this is really true—will have a table set up in the garage or wherever, or plastic chairs, someplace where people are getting together. Then you go to Princeville and it’s not like that. The houses are all closed off. There are these beautiful lanais, but no one’s sitting on them.

It’s interesting that Hawaii, which seems pretty rural, is also so liberal. I feel like that’s rare in America, at least in the mainland.

Yeah, Hawaii is the most culturally liberal place, it’s the most liberal state in the country. Part of that is the Hawaiian people are liberal in a really authentic way of having a lot of compassion for others. For Hawaiians, masking was a no-brainer. You mask up because you’re trying to protect your neighbor. It’s a way of being a good community member. It was just so clear and simple, and it was bizarre to me that it wasn’t simple everywhere.

At the same time, there’s also a lot of annoying political liberalism where people are very, very anti-GMO, for instance. Obviously that’s a big thing in the book, this conflict between agriculture and technology, and one of the things I was really trying to do—and this goes back to preaching to the choir—was to say that I don’t think any of these arguments are simple. I don’t want anyone to read this book and think, “I agree with everything here.” I want you to be challenged a little bit, because that’s the only real, honest way to look at this situation, which is to say that, yeah, these companies are destructive, but they also offer jobs. That’s a tradeoff that’s often unfairly exploited, when they say, “We can’t regulate these industries because it will kill jobs.” I think that a lot of that is BS. At the same time, there is some truth to it. It was important to me to capture those conflicts, and for readers to feel conflicted themselves.

I thought you did a great job of humanizing Lindstrom, the CEO of a big agrochemical company.

Another origin of the novel was an article in The New York Times Magazine by Nathaniel Rich. DuPont was dumping toxic chemicals into these streams in West Virginia, they were poisoning people and poisoning cows. They ended up making the movie Dark Waters about it, with Tim Robbins, which came out a few years ago. I read that article and it was so clear that these executives at DuPont had been choosing to dump toxic chemicals into these streams. Someone had signed off on this—a lot of people had signed off on it—and I was just like, what is this person thinking? You want to believe that they’re a bad guy, they’re just a bad person, but they could be your next-door neighbor and be a really nice person. Not just to put it on them. I think we’re all culpable for some of this stuff. We’re all living lifestyles that are destructive. We’re all buying these products. So how do any of us justify what we do? But more specifically, how does anyone justify those terrible things?

I did a bunch of research, like I read Obedience to Authority by Stanley Milgram, which says that it’s human nature to follow orders. That was one of my goals, to understand that psychology. My ideal reader would be an executive with one of those companies, or someone in a similar situation, who reads it and maybe is sympathetic to Lindstrom—because I do think he’s sympathetic—but at the same time, this executive comes to the end of the book and thinks, “Oh, whoa, I did some fucked up shit.” (Laughs.) That would be the best possible result of this novel.

You didn’t have kids when you started working on this book—now you have two sons. How have they changed the way you view or approach your writing?

We have these two insane toddlers running around, and they kind of rule life. No matter what else is happening in our lives, the biggest events, it’s like, “Nope, gotta play trains with my kid at eleven o’clock at night.” They’re my saving grace, because when I was younger, I felt like my life depended on me becoming a good writer, and if I was a failure . . .

I mean, I still feel like that to some degree, because I made a lot of professional sacrifices to keep writing. If I hadn’t gotten this publication, it would have really been a blow. Once you have a book out, you can at least point to it and say, “Well, whatever else I did, I got that one out in the bookstores.” I’m really grateful to all the people who made that possible, because I’m really fortunate. There are a lot of good writers, great writers, who just don’t have the fortune or haven’t met the right people. I got lucky in a lot of ways.

But more than anything, I want to hang out with my kids. I want to have a nice family life, regardless of whether I publish a book or don’t. Whatever happens with my career is secondary to that. That’s been a real gift in that I don’t feel like I have so much staked on my writing. I feel at peace as a person in a way that I didn’t when I was twenty and aspiring to be a writer.

The biggest thing about my book being successful or not—I mean I would love to get that validation of my craft, but more than anything, I would love to quit doing my other job. (Laughs.) I’d just have more time.

Evan Allgood has written for The New Yorker, The Believer, McSweeney’s, Vulture, Paste, and Los Angeles Review of Books. You can read more of his work on his website.

This post may contain affiliate links.