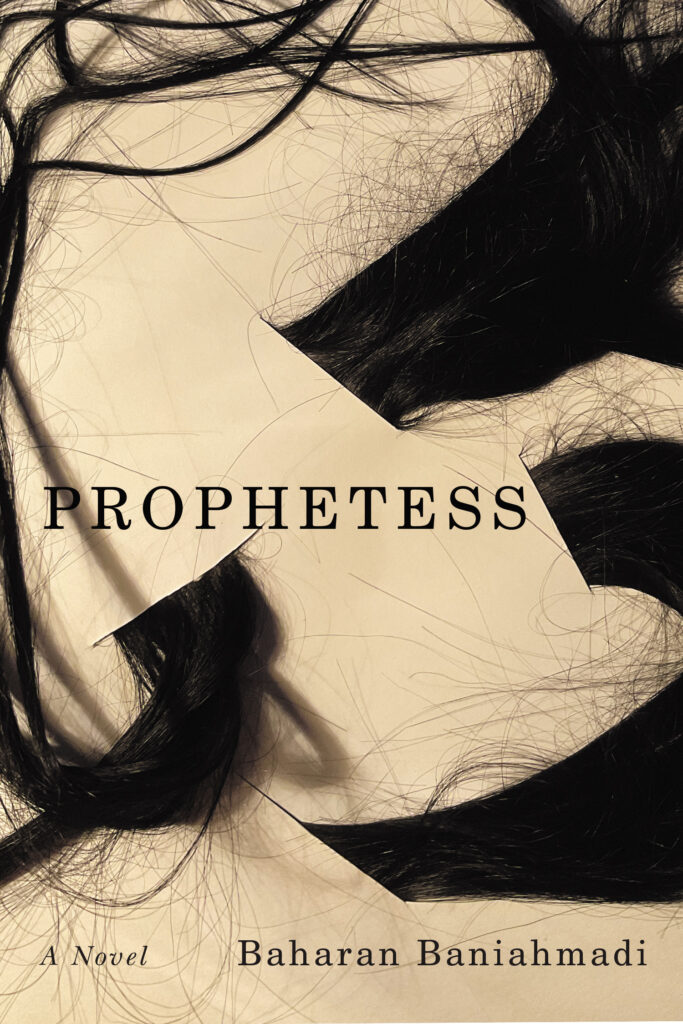

[Véhicule Press; 2022]

Prophetess has a curious backstory. The novel, written by the Tehran-born actress and author Baharan Baniahmadi, may have had a co-writer, or an undisclosed translator. Tucked away in the Acknowledgements of the book is this elusive note:

Special thanks to a friend, without whom this book could not have been written in English in the first place. They asked me, with absolute humility, not to mention their name. Perhaps if they lived in a different country, I wouldn’t have listened and mentioned their name anyway.

How should the reader interpret this puzzling statement? Should we consider Prophetess a novel in translation, done by this unnamed “friend”? If the novel has been translated, or co-written with the help of another person, then why not frame the novel as translated by “Anonymous,” as was done with Shokoofeh Azar’s Man Booker International Prize-nominated 2019 novel, The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree?

Prophetess, however, is adamantly not marketed as a novel in translation. Nowhere in the text is reference made to the book having been written initially in Persian (Baniahmadi’s first language), and then rewritten in English. The process by which Baniahmadi came to publish Prophetess in English remains just out of view. The Acknowledgments hint at the possibility of translation, yet do not go so far as to announce it openly.

On one hand, I am aggrieved that the violent political realities of contemporary Iran have made it so that writers who publish works seen to be critical of the current regime may fear for their safety. In the wake of the assassination attempt on author Salman Rushdie, such fears seem particularly salient. The attack on Rushdie shows that there are, unfortunately, quite legitimate reasons for this “friend” to wish to withhold their name from the publication of Prophetess.

But on the other hand, I am pained by the lack of clarity on the role of this “friend” in the creation process of Baniahmadi’s novel. This eclipse of the book’s linguistic backstory seems like a missed opportunity to spotlight on the various forms of rewriting and collaboration (including translation) that often make up a novel such as Prophetess. Given that so many translators are working to have their craft more widely acknowledged in Anglophone literary culture, the erasure of a possible translator from Prophetess strikes me as an unnecessary slight to the work of translation, and to the premise of collaborative literary creation in general. Would labeling the book as a translated piece have degraded it? Certainly not, in my opinion.

The murkiness surrounding this uncredited translator-friend aside, the prose of Prophetess is a simple delight — at once lucid and addictive.

*

The novel is told from the perspective of Sara, a seven-year-old girl living in the poor, downtown region of Tehran during the years immediately following the ‘79 Revolution. In the book’s opening segment, Sara witnesses the horrific abduction of her sister, Setareh, by a male neighbor. The traumatic event causes Sara to become mute, and to cut herself off from others. Although Sara had previously been scolded for her loud voice, and chastised for her tendency to overflow with tears, screams, and questions; after Setareh’s abduction, Sara ceases to talk at all.

Throughout the four parts that make up Prophetess, we follow Sara as she withdraws further into herself. She develops grotesque and fantastical protective mechanisms (peeing herself, spontaneously growing hair from her face, turning her dark, youthful hair a grandma-white) that serve to keep men away from her. After her sister’s disappearance at the hands of Uncle Moji, Sara cannot stand to be near any man. Sara is still a seven-year-old girl, but the grief of her sister’s absence causes her to feel as if she has aged decades overnight. “I am not seven years old anymore. I haven’t been seven for a few days now. I can feel it. I am one hundred and fourteen years old,” Sara states matter-of-factly. “I am an old woman in the body of a child, unable to speak.” Slowly, she begins to sense the presence of all the world’s women in her own body, women who have been wronged by men or society in general. These voices fill her, erasing her own. “Everybody calls me the silent girl,” she tells the reader, “but my world is full of noise. It’s all noise. The voices of a million people crawling inside of me.”

As Sara tries to keep male danger away from herself, she also seeks refuge in religion. Words from the Quran offer her a sense of peace. The mosque becomes her “shelter” and refuge. She likes to lie on the floor of the women’s section of the mosque, staring up at the tiny flowers that speckle its blue ceiling. “My brain can stare at the blue ceiling of the mosque for hours and in its patterns create a better world for itself. A world in which good people go to Heaven and bad people go to Hell and justice is fair.”

*

Prophetess is a page-turner. I read the novel in a few hours one summer’s evening, thoroughly enjoying the smooth pace created by the short, bare sentences. But some of the most interesting parts of the story come in its unexpectedly outlandish, or sinister, twists.

A few chapters into the book, it is discovered that Sara can speak a variety of foreign languages fluently while unconscious. Soon after, the religious people in her neighborhood latch onto Sara as a sort of child prodigy—the “prophetess” of the book’s title. A “kind Polish psychologist” takes an interest in her case, and tries to help Sara work through the emotional sources of her mysterious multilingualism and strange bodily changes.

The entrance of the psychologist sanctions an exploration of the darker parts of Sara’s mind. In one chapter, Sara narrates a dream, in which the kind psychologist gives her a machine gun and a knife. She uses the weapons to take revenge on her school classmates, the other neighborhood children, and her own family—people who she sees to be complicit in the oppressive and unjust social system that enabled the disappearance of her sister. Sara’s tone stays unabashedly light, even as she tells of her horrific dreamscape: “They’re all shocked when they see me with a machine gun. Loqman bows his head. Plop, plop, the sound of the ball bouncing in the blood. I enjoy the beautiful scene.”

After going on a shooting rampage throughout the city, dream-Sara realizes she is the only person left alive.

I walk past the stores, parks, candy and ice cream shops. I have killed everyone. Now I can eat as much ice cream as I want. I can eat jam straight from the jar with my finger, and nobody will say anything. I can eat all the expensive food with nobody to tell me I can’t afford it.

The dream allows Sara to not only express her outrage at the absence of her sister, and the cruel mocking of her schoolmates and the other neighborhood children, but also demonstrates just how perturbed she is at the injustice of the socio-economic inequality that has thus far structured her life. In her dream, fairness means that she can inhabit the whole of Tehran, not just the narrow, small, “khaki” colored streets of her childhood.

*

Sara’s surreal protective mechanisms (her sprouting beard glands and lowering voice), however, allow her access to spaces restricted to her due to her gender. With a turban wrapped around her head, and the sudden emergence of a beard, Sara is able to pass as a man.

At one point, she becomes famous in her neighborhood mosque in Tehran as a Sheikh—a knowledgeable, wise man of religion. “There is a man emerging in me,” Sara says. “I am a woman and, when I pass the curtains in the center of the mosque, I am a man.” When the local news catches word that “the messenger has the power to switch genders!” and the town begins to close in on the teenage Sara in earnest, she takes the help of the Polish psychologist to flee the country. A swift evacuation operation turns Sara into an exile in Canada.

Despite Sara’s unexplained and uncontrollable fluidity between genders, she staunchly refuses the flexible gender labels offered to her by Canadian society. She scoffs at the terms “genderless or non-binary.” Instead, she zestily reaffirms her cisgender, feminine identity, remarking that: “I am a woman who has been assaulted by men many times throughout history. My defense is to become a man during encounters with them. But I am a woman.”

Despite her vehement disavowals of who she is not, Sara ultimately remains uncertain about who she is. “I am not how others describe me. Who am I?” “What does Sara want?”

*

Prophetess is the story of one girl coping with immense personal grief, along with larger socio-economic inequities. Its most brilliant moments come in its more bizarre vignettes, and its duller ones crop up in trite sentences like these: “Holding a grudge feels like prison. Hatred is poisonous and kills you slowly,” or “I think we all come to this planet for a reason.” But while the crisp clip of the plot and the delightful strangeness of Sara’s supernatural coping mechanisms are sometimes marred by such clichés, the novel’s prose is tightly-wound enough that such awkward moments are easy to breeze by.

Baniahmadi and her unnamed “friend” (and possible translator) are a lively writing pair. I will be picking up anything the two collaboratively create in the future.

Anna Learn is a PhD student of contemporary Persian and Spanish-language literatures at the University of Washington. She received her MA in Comparative Literature in 2019 from the Universidad de Salamanca, in Spain. She is particularly interested in short fiction, women’s writing, and translation studies.

This post may contain affiliate links.