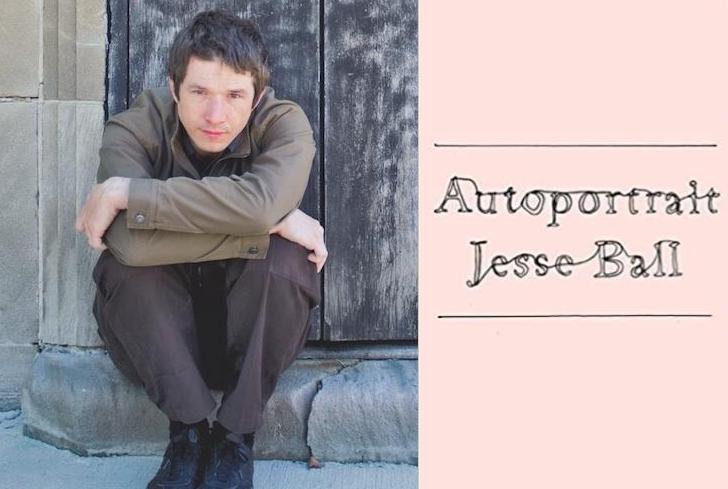

I first encountered Jesse Ball’s work when he visited Temple University in 2014. He gave a reading I remember fondly to this day—which is to me notable, as 90 percent of the readings I’ve attended are world-historically awful. I read almost everything he had published, and since then have continued that habit. Catapult has just released a new title of his called Autoportrait, modeled after a book of the same name by Édouard Levé. In it, Levé writes a collection of non-linear, matter-of-fact sentences about himself. It is an odd and striking form of self-portraiture. I was delighted that Jesse Ball had written his own version of this text, and found the results similarly moving. The following is my conversation with the author.

Sebastian Castillo: I’m a great fan of Joe Brainard’s I Remember. When Harry Mathews told Georges Perec about the book, Perec was so taken by the concept that he wrote his very own I Remember (Je me souviens). It strikes me that you’ve done the same with Levé’s Autoportrait. What drew you to Levé’s book, originally?

Jesse Ball: The first one of his I read was Works, which I found interesting and acceptable. Then Suicide, which riveted me, and finally Autoportrait. I believe I began the Newspaper once but didn’t find it compelling. Immediately, I felt that his approach to what a book is or may be is/was similar to my own. But I didn’t think to use his approach until years later, when it occurred to me that I was the same age he was when he wrote his. That sameness led me to the attempt. Of course, mine is not very much like his. Our characters are very different, I think—what we would want to conceal, to reveal, even what it means to conceal or reveal. He shows himself very precisely, in fact so precisely that one wonders where he is. I do not think my obfuscation is in that particular key. But I will leave it to someone else to decide how and why I hide whatever I have hidden.

In the book’s acknowledgements, it says you wrote Autoportrait in a day. When I saw you read back in 2014, you mentioned that you’ve written most of your novels in six to eight weeks. I’ve found your books assured and elegantly written; none of them bear the trace of their rapid composition. That was the case for this book as well. To what do you attribute your writing speed? In past interviews, you’ve spoken of the urgency you feel when sitting down to complete a text. Does that urgency always return?

In fact, it is usually a week to write the books, not six to eight. I don’t know what I would do over the course of six to eight weeks. The composition in six or seven days is very musical, like a performance, complete with a protracted sympathy for atmosphere, a threaded passage in which the continuity is more crucial than the perfection. But as you so kindly say—the elegance of the writing is important to me: not so much as elegance per se, but as specificity. I always mean something quite particular, this not that, and this this not thatness is crucial to the elaboration of the imaginative parade. It is what draws my mania and allows me to work joyfully for long periods without much rest.

I think that the speed has to do with various things: My beginning was in lyrical poetry, and in particular within the paradigm of Lorca, whose duende-notion has always electrified me. Let the demon enter, howsoever it may appear. If it will spin the wool you were to spin, or weave the cloth, whichever metaphor you choose, leaving you with many, many bolts of cloth come morning, so much the better.

I have never had any faith in ideas of originality or concrete human identity. Things flow through us. Our work isn’t ours and can’t be. This makes it easier to stomach the pitchdark embarcations of sudden book composition. Some of my friends are and were musicians, especially classical pianists, and when they must perform in concert, they go out into the piece with great bravery. They cannot fix things that have gone wrong, save by weaving the errors into ongoing playing. I think their examples were helpful to me.

I’ve found constraint-based autobiographical writing opens up possibilities that otherwise would not have occurred. How would you describe your experience of writing Autoportrait in the moment of composition? Were there any memories you recalled that surprised you?

Would that I could say something about this. I recall very little from the day I wrote it. Catherine Lacey brought me lunch. I know that happened. Also, my dog came sometimes to scratch at the bedroom door. I had some concern about the continuity and consistency of my naming scheme; I believe I began by naming some of the people referred to, but later went through from the beginning and removed all names as such. It is important in a work, even, or perhaps especially in a swiftly written work, that there be extraordinary consistency. Otherwise, no effect can be apparent.

My experience of finishing this book, as well as Levé’s, was a private sort of readerly feeling that I knew you. I understand enough now that this is one of the intentions these kinds of texts seek to create—perhaps the same could be said for all writing in a confessional mode. What would you say is something about yourself you have left out of this book?

If I had written it the following or the previous day, I’m sure it would have been quite different, let alone the previous year or following year. Some dear friends of mine were, sadly, left out entirely, and not on purpose. Many fine anecdotes happen not to have been included. There were certainly a number of hilarious and ribald anecdotes that I couldn’t include because they paint me in too pleasant of a light. One should always maintain an atmosphere of self-deprecation in memoir.

And again—it is a portrait, not a memoir, so it is from one angle. A different angle would show something else entirely. I suppose your question is: What is one of those things? I would imagine some of them must suggest themselves to you as a reader of my work, and as a person who has met me. In truth, my own experience of reading the Autoportrait is perhaps not sharp enough to know what is not there. Seeing absence is harder than seeing presence. I am mostly vegan, Buddhist, anti-human. I am not sure how much I sound the anti-human note in Autoportrait. Another book, Comedy of the Bones of Your Face is all about that. I don’t know when it will appear, though.

In the book you say, “I love being sad, and in fact, it is a weakness of mine to allow myself to be sad for too long.” I understood what you meant. Do you think this feeling creates the urge to write about oneself, or does that feeling arise from elsewhere?

Were it not for the Levé book I doubt I would ever have written about myself at such length. To have the excuse to flirt with his marvelous procedure and see whether I too could find something of value . . . it was a joy embedded in technique, in medium. That’s what makes the thing flow from page to page, if indeed it flows. It should be like an overheard conversation. The adoration of the technical and of the demands of a medium, especially as embedded in previous slices of time, in histories, are I think undersung strengths in a would-be writer. This is a reason to cavort through all the previous centuries in search of maneuvers and modes. Those lonely voices sounding from far off centuries could lend immediacy and power to what I find to be an impoverished contemporary landscape.

In the book you mention your enjoyment of the film Goodbye, Dragon Inn. I love that movie, too, as well as every movie I’ve seen directed by Tsai Ming-liang. My favorite is What Time Is It There? To what extent would you say film has made a unique impression on you as a writer, if at all?

An enormous impression, almost the equal of poetry. I don’t know that the impression is unique. Everyone should and can be undone by Tsai Ming-liang. There is something in the avowed minorness of Goodbye, Dragon Inn that delights me, and that has given me permission to write many of my own somehow small books. Sometimes people speak of Kafka this way: a minor literature. Let us leave the great things and move on to small coherent things, minor things such as can be hidden in a coat. Let’s have a whole book to simply chart the physical accent of a single person’s speech, or to describe light on a seal’s wet and wriggling back.

You have published many books, and written more than you have published. Do you have a favorite?

For a long time, I liked best Pieter Emily. But now . . . I don’t know. Each thing to its time and place. I guess I am fond of recent things. Maybe Here on This Black Hill, a short novel I wrote a couple years ago? There are parts of The Children VI that I very much adore. That one you can read now if you read Spanish.

Sebastian Castillo is the author of Not I (word west press) and 49 Venezuelan Novels (Bottlecap Press). He lives in Philadelphia, PA.

This post may contain affiliate links.