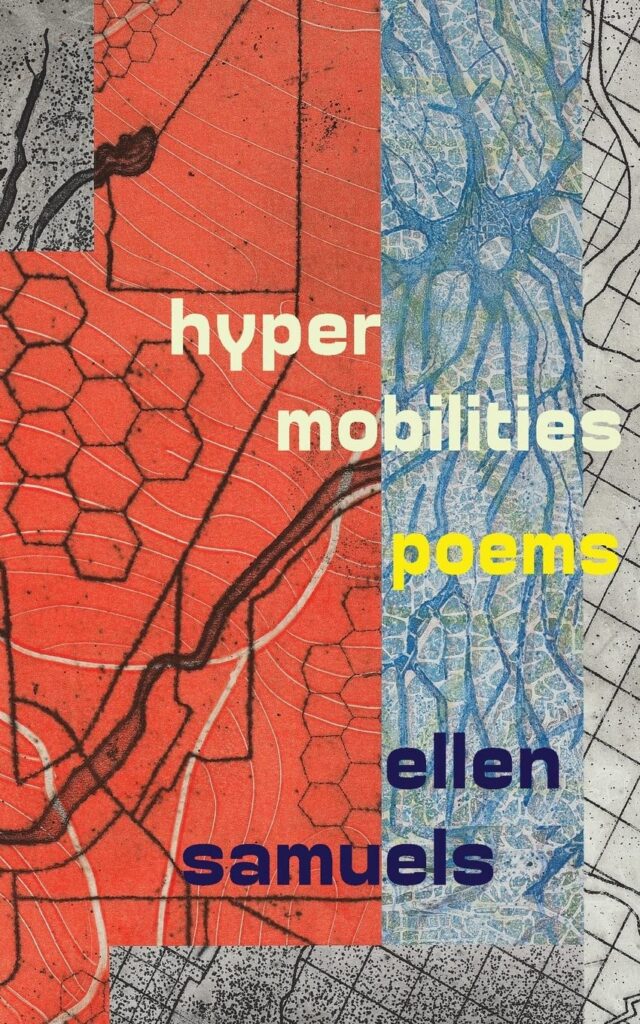

[The Operating System; 2021]

Ellen Samuels’s Hypermobilities invited me in through the form. Indeed, the book may call to readers who share some aspect of being hyperaware of one’s dexterity, whether physical or mental. I don’t understand every aspect of Samuels’s language or system of being. I don’t personally connect with the title. While reading, I wondered what a hypermobility could be, why whatever it is it gets called a hypermobility, and what kind of hypermobility she is describing. The book explains it’s based on her own experience of joint hypermobility, but I am left after the end of the book still not entirely sure what the illness physically feels like. It’s hard to conceive of all the symptoms happening in tandem. The symptoms could be hers; they could also be ours. (She offers further testament to joint hypermobility in an endnote. I think it’s significant she chooses to put this part at the end, and I would encourage readers to enjoy the haiku and not start there—to appreciate the poetic resonances in and of themselves, beyond her particular life experience, to resist reading poetry prescriptively.) I am inspired to forge a connection to the capacity of mind. What does it mean to stretch or practice the agility of the brain?

The book opens with a section on “Hypermobility,” including a single haiku titled “Hypermobility.” The opening is inviting to everyone. So many experiences could be invoked in the affect of the statement: “No one is supposed / to.” The poem continues to turn about how we stretch ourselves beyond our breaking point: “to bend that far.” It speaks in a way we all understand, even while it acknowledges our feelings of total aloneness in the fight. In the very next breath, the next word falls out of the heart, off the tip of the tongue: “No one knows. / Why you don’t just break.” Several of the following haiku in this section continue to explore the metaphor of opening and closing, bending and breaking. It’s interesting to me how the body-mind opens through illness. We tend to stay so closed within ourselves. Of ableist minds, we may think someone stuck at home is more closed up, but they may actually be opening inside, required even by the very vulnerability of illness to adapt, becoming more open-minded to embrace themselves. Disability activists think outside the box because of the failure of our society to accommodate, to imagine more expansively.

Disability activists are leading innovators today because they are so driven to problem-solve and redesign a world that will operate better for them. In “The Difference Between Joint Subluxation and Dislocation,” Samuels writes, “Door unlatched in the body-house.” We may “shudder” at the thought of moving slowly, moving in pain, moving with and through vulnerability. A poignant moment that stands out in the poem is “kiss the jamb” because it is something we wouldn’t be prone to do, let alone offer gratitude for. Poem by poem, Samuels invites us to overturn experience and discover new thought, like a trip into her mind. Another haiku from this section, “Hypermobility of the Small Joints,” emotes mobility struggles in a way that may translate across the spectrum of experience. Through the poem, we are transported to the circumstances of everyday tasks. Samuels writes, “To press a button / means fingers muscle past bone.” There’s a pain in doing little things like opening a door, even so it’s worth it. I love the final line: “Yes, No, Enter, Yes.” Through the affirmative reasoning process from “Yes” to “Yes,” we hear a piece of the self-talk wrapped up in proactively completing the task. On a larger scale, the poem is about enduring pain, moving through life with it, though not necessarily overcoming it.

I find myself often reflecting—what does it mean to reclaim a hyperactivity attached to one’s identity? So often “hyper” has carried a negative connotation. I think of friends on social media posting more and more about discovering an ADHD diagnosis later in life. I think of the process of coming to terms with it as an adult, perhaps offering both relief and pain from never knowing before. I think of experiences I understand like hypervigilance and hyperarousal. Neither is necessarily a constant state, if that matters, to constitute “hyperactive.” I don’t claim to be a master at psychology. I can only write from life experience and imagination, research and speculation. Still for moments in time, however long an “episode,” many mental health warriors and trauma survivors likely relate to the feeling of being flooded when the mind becomes hyperactive. In such states, for me, Samuels’s text is highly charged and ever destabilized. The moment after, it may mean absolutely nothing, cut off from the great rush of personal contact. I’m left with a chain of unclear signifiers. All signs linked only by the rush of the moment.

Perhaps both to express and make peace with what feels like a strange process, I’ve been striving to embrace the hypertextual. I go with the flow when ideas come in waves, perhaps piled up on top of each other in my mind, which has been working so tirelessly to unwind something heavy. They just suddenly all spill out at once, overflowing. I write it all down. I write it all down anxiously, afraid I will forget what just suddenly came to me after maybe days, weeks, months, or years with a clouded head.

This is where my process diverges from Samuels, who supposedly wrote in short form because she could memorize a haiku. I am afraid I cannot recite any one of them from the book, even as I know I was touched by many in a way hard to explain. I could read a nugget and engage with it deeply in just a few minutes, then move onward. The speed of my thoughts is only compounded by the speed of trauma triggering, like rapid fire transference. What some may call intrusive thoughts certainly make it challenging to focus on reading for lengths at a time. I’ve found that dense books tend to also be very heavy, so reading is often not a consolation but a trauma, the ease of reading a rare treat. I feel guilty as a writer to not always indulge in reading, feeling I am supposed to focus on learning techniques from other writers perhaps more than just discovering my own. Samuels’s book of haiku was a welcome respite for the mind caught in the down-low by fatigue and exhausted by the performativity of “well-read-ness.”

The spirit of Samuels’s work reminds me that it’s good to embrace a more mindful writing practice by slowing down the reading and writing, taking smaller steps and stopping poems short. In the rush, speed, and energy of notetaking, we don’t have to get down every thought all at once. The closing line from one of Samuels’s poems, “That’s enough for now,” strikingly reminds me of an affirmation I learned elsewhere. “That’s enough for today” was what the breathing specialist Betsy Polatin has been known to say when closing a mindful breathing exercise. This was interesting and memorable to me because it was a revealing and affirming line. Betsy Polatin’s meditation project Humanual draws attention to breath; knowing even this could cause anxiety, she deliberately encourages just taking a few moments of meditation in that space and gently closing it. Likewise, the practice of freewriting is an opening of the heart, and we don’t have to do it all at once. We don’t have to open to the point of pouring all out and breaking apart. How do we know how far to bend? We can only try to regulate ourselves, our thoughts, our emotions, and our bodily flows. This is what Samuels’s haiku “Hypermobility” asks us to consider and let go, without expecting to ever quite have the answer. Her story shows us that our bodies may decide how far we go. Our bodies may go further or not as far as we hope to go.

Certainly, in a capitalistic society, we value product over process. We want a dense, compact product. The idea of a “project” with a particular “frame” or “theme” may help a writer. Picking up this book while presumably a passing able-bodied self, I find great comfort and richness. As I have been ever so consciously striving to build a poetics of care and meditation, I am grateful for the poetics of disability that so freely and gracefully combats ableism on the page through both form and function. It’s liberating to think about a manuscript as a collection of short forms. It’s liberating to think about a writer (and editor) caring about a reader who can only read in small nuggets and pieces. At a time when reading has continued to be a struggle for me, I took comfort in this book because it was a quick and easy read. I appreciate how fast I could enjoy and connect with the text. It was sharp and compact, deep and precise, in a way that cut when it cut but was over in an instant.

Reading the book reminded me of what we carry in our bodies, even as we approach reading and writing. The title of Section 3, “Coloring the Pain Book,” perhaps prompted the most curiosity because it inspired me to color my response to the book, even as I felt compelled to assess my own sense of pain and the pain scale alongside Samuels’s story. Pain is challenging to measure, so I found her poetic approach to be very innovative. For example, in the haiku, “Tylenol with Codeine,” Samuels compares pain to taste. It’s an interesting point because pain is a sensation, but perhaps more clearly felt like touch than taste. She writes, “If pain like a taste / could be rinsed and wrung, swallowed.” The last word is forceful: “swallowed.” In pain, we may tend to feel stuck, not free to move, even commanded or warned not to, in a state of emergency: “don’t / move. Don’t think aloud.” I hear caution. Take it slow. I hear what no one wants to hear. Ever yet, we are existing, so we are enduring.

There’s a grief in just searching after a cause of illness and the family trauma that ensues. It may be a triggering process, reopening an old wound and causing more pain. Samuels’s turn to a look at blood seems to spiral downward: “Blood-deep in you.” This turn may weigh on a reader; shifting the gaze upon our blood-relatives can be particularly heavy. The poems start to look to the mother for “a sign,” “a photo,” for example. She writes in “Autosomal Dominant Inheritance,” “This body knows what / your mother did not— what / she gave, this body.” If you can imagine the visual of the page, of the gaze falling down the page, attentive only to the line endings, it is powerful to note how the lines fall: what, what, this body. The poem is begging the question “What?” and the answer to “what,” “what,” seems to be “this body”—genetic inheritance, a perhaps unknown and unintended hurt, and with that an unspeakable pain, much like the pain of an inherited pattern of trauma.

Ever writing bits and pieces, it takes some time before I see how and if the pieces all connect, much like recording and making sense of a strange case of disparate symptoms. In the second section of Samuels’s book, “symptoms and signs,” many poems center common symptoms known to many states of illness and emergency, so I can relate, even as the symptoms resonate differently with my own focus on trauma response. For example, the initial turn to nausea and heart rate was striking. Such symptoms present a relatable starting point and a heightened state of alertness. Other poems look at common symptoms like sleep patterns, fatigue, and palpitations. From a trauma-informed standpoint, all are common sensations related to panic attacks. That said, the continued resonance prompts me to contemplate the relation of the body to the mind and memory.

When Samuels speaks of gastro reflex, she opens a question for readers too: Is this a case of genetic makeup? Or is it a case of my body responding time and time again to something, my body maladapting, something unresolved? Samuels writes, “Not stomach but throat.” Sensing that the throat is the focal point of greatest pain, she further describes it as “Gravel-stuck” and “gnawed clean to bone.” This stark metaphor is almost nauseating to read. I feel it in the pit of my stomach. It only gets worse. The haiku, “Delayed Gastric Emptying,” takes us deeper into the operation like a “Too-full elevator.” What “returns to top” is felt. In fact, it’s interesting how the poem turns from the metaphor through an actual experience to an emotional center. We can taste some element of the experience, theirs or our own, triggered in the poetic act. It could be “butter” or “toast.” It could be a body exhausted, tired and numb. All considered, the “Unhungry heart” conveys how it’s a thing of our bodies somehow tied to our hearts. If memory triggers hyperarousal and hypervigilance, like a panic attack, what rises up the esophagus then must somehow be the product of both our body and our mind.

Samuels’s narrative in haiku poems, verse nuggets, or snapshots feels like something I can hold. In fact, the story of Samuels’s writing project is so much about overturning symptoms and enduring a life with illness, so the book invites readers to reflect on how to hold their own pain as well. In “Magnetic Resonance Angiogram of the Head and Neck with Contrast,” we discover a beautiful image of water connected to knowing and caring for one’s mind or brain: “There are blue rivers / running your skull-lines.” The next turn of thought as the second line breaks into the third is a powerful moment: “Hold so / still you can feel them.” How do we hold the incomprehensible, something not entirely immeasurable, but ever still mysterious? Through the turn to water, an uncontrollable and unknowable force running through all our lives, our body-environments even, maybe we can find a new fascination. We discover a sense of living in common, as fluid organisms of ever-evolving and adaptive consciousness.

One of my favorite haikus in Samuels’s book, “Bath with Epsom Salts,” evokes a divine sense of transcendence and immanence: “If the giant who / held the sky could for once lie / down in this warm sea.” I enjoy the picture this poem offers of rest, especially for the constant fighters. Samuels even compares the body to the “Planet’s core,” a mystery we hardly know. When blood pours out, we may even become light-headed, detached from both mind and body: “you, the vein / . . . opens and pours” like a river or “vein-road.” It’s curious, opening up. How much do we actually know our own depths? What spills out may be overwhelming and shocking even to ourselves. Through a more expansive imagination, we may find a new way to look upon our own bodies with more respect, compassion, and care.

Reading Hypermobilities may illuminate the way poignant metaphors extend beyond one lived experience, so a single story may translate across diverse experiences of disability, illness, and trauma. What is shared may be chronic, so the instinct to survive and thrive is impactful. Samuels conceives of poetry beyond mimesis, figuring the poem as both “mirror” and “pond,” like “both / ways to drown and see.” Is this how visual metaphors strike another chord? The bodily affect of Samuels’s poetry commands our full attention; for example, her description of “Vertigo” leaps off the page, “The world we’re on / is always spinning. Maybe / you’re just standing still.” How do we measure cognitive functioning? Samuels speaks to the madness of our ableist projections. I empathize. It’s difficult to pinpoint where physical pain meets emotional pain. Mental illness arouses all the senses.

Kara Laurene Pernicano (she/they) is a multidisciplinary artist and poet-critic. Through hybrid arts, she seeks to awaken an interpersonal approach to trauma, grief, talk therapy, and mental wellness. Kara is pursuing her PhD in Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies at Stony Brook. She has a MFA from Queens College and a MA from the University of Cincinnati. Her creative work has appeared in or forthcoming in Snapdragon, Waccamaw, The Humanities in Transition, Full Stop, the winnow magazine, ang(st), Passengers Journal, and Newtown Literary.

This post may contain affiliate links.