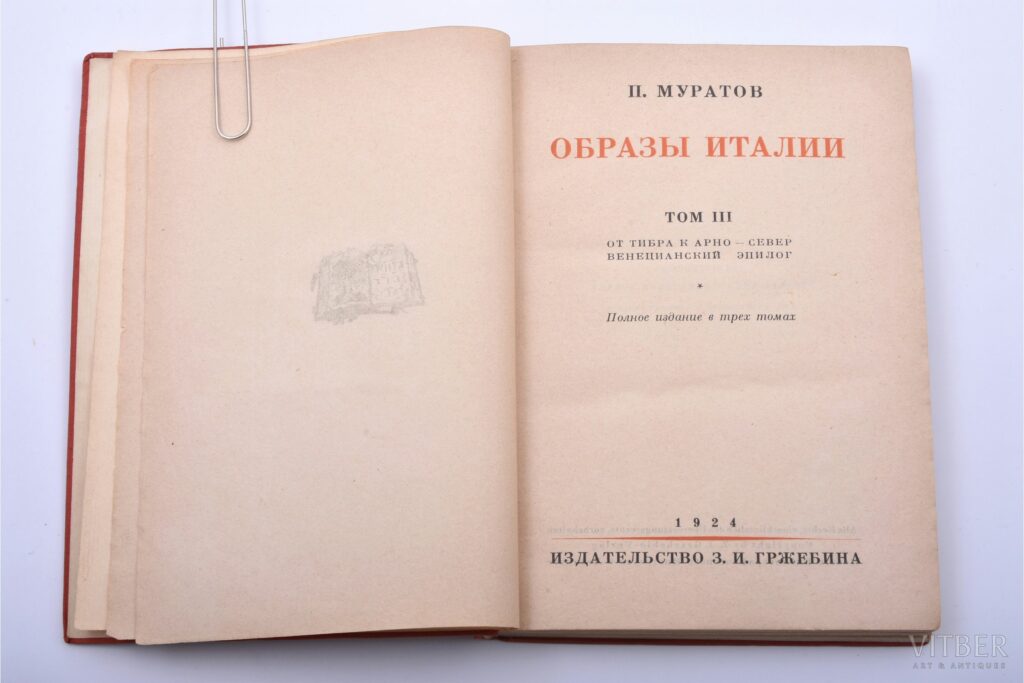

The following is a translated excerpt from Pavel Muratov’s Obrazi Italii.

Entering Pompeii one is surprised by the continual stream of foreigners to be found there, regardless of the hour of the day or time of year. The very gates of the ancient extinguished city resound with the discordant bustle of hotel and restaurant life. Guides bark their services with spasmodic insistence, and when you see an infirm old traveler sitting on a stretcher it starts to seem that everyone gathering here is looking for a cure from some sort of sickness – a cure that the walls of Pompeii seem to promise

The impression is not necessarily a false one. For a hundred years, Pompeii has served as proof of the powerful wish, hidden somewhere in the heart of man, to make contact with antiquity. It would hardly be reasonable to call this simple curiosity. The modest dimensions of the Pompeiian miracle would have disappointed the merely curious long ago. Simplicity, order and unity govern the streets of Pompeii; in this city it really is a simple matter to number each house and section, the way today’s archeologists have done. Abandoned by life, Pompeii has lost the picturesque spectacle of everyday living. The figure it presents now is no more than a painting made of stone and air.

The feeling of stone, which is one of the most important feelings of ancient life, can be felt with unusual strength on the streets of Pompeii. And the heat of the sun is nowhere experienced so vividly as on these stone streets. The Pompeii of today is almost devoid of coolness, but the thought of shade informs every ruined Pompeiian house and courtyard. Beneath this cloudless sky, shade was classical man’s devoted companion over the course of his day, the first wonder of the world that the child of antiquity opened his eyes upon. Its stripe led the long straight streets, delineating the ovals of the theaters and the squares of the peristyles, pooling in the cannelures of the columns and etching every detail of the entablature. Its animating gilt is the only thing that has not fled the walls and cobblestones of Pompeii.

It is because of this that the architecture of the Pompeiian house is suffused with an airy play of light and shade. In shade, the natural pale-blue or golden coloration of the stone shows itself; but this vanishes under direct sunlight, dissolving in the sparkling summery whiteness of the Campanian noon. The desire to rest one’s eyes leads them towards the varicolored walls and columns inside the atriums and peristyles. The street meanwhile remain uncolored, without a single harsh spot to mar the brilliance of the blue distances.

The Pompeiian did not spend his time on the street; his life outside the house ran its course in spacious forums, baths, and theaters. And far more important to him than this shared social life was the domestic one that he lived behind his walls. Love for the home built Pompeii. Never since then has man taken as much pain and derived so much joy from existing in his own private cell. What astounds us about the layout of the Pompeiian house is its attempt to divide space into the smallest possible compartments, and to fit these compartments against one another as snugly as possible. The small dimension of the rooms are surprising, but no less surprising is the fact that some of these houses contain upwards of sixty such rooms. In the midst of these innumerable bed- and living rooms, which could only be distinguished from one another by the house-proud patriarch, stretched the inner courtyards – the half-open atrium and the fully-open peristyle. With amazing regularity, these are repeated in every Pompeiian home, in the exact way that, on the streets of the city, we see repeated the identical cisterns, corners, counters. Regularity and order, in this way, ruled both on the street and inside the home; the good will of classical man made them a part of family life. The daily round of that life unfolded with the regularity of a religious rite. Holy laws, it seemed, governed it; holy were its simple phenomena, and the house itself – every Pompeiian house was a temple of lares and penates.

Sometimes it seems that it was only because of the strict order of its houses and streets, this severity of form, that Pompeii was preserved so well beneath the ashes of Vesuvius. Antiquity did not dazzle the newcomers with treasure when they unlocked it from beneath the earth; what it brought with it into the world was a new type of rest, a sort of bygone affability, as if the vanished hospitality of the Pompeiian house with all its decorations really had been born again amidst its ruins. One after another the traveler visits these houses, shedding not a tear for the numerous tools of daily life and remains of paintings that have been transferred to the Neapolitan Museum. For some time now science has been working to complete the city’s devastation, strangely enough, and it is only recently that things have begun to be left where they are found. Because of this, the only place where one can get a true understanding of the Pompeiian house is in the two large villas that have been opened up over the course of the past fifteen years: the Vetti House and the house of the “Amorini Dorati.” In the Vetti House, one can see entire walls of various and superbly-preserved pictures. The hanging masks and fragments of sculptures in the peristyle of the Amorini Dorati remain some of the most beautiful reminders of Pompeii. The part played in this reminder by the painting itself is comparably slight; what stays in one’s mind above all else its background – of red, black, and yellow – which is painted with uncommon strength and purity of color. The tiny flying figures on similar backgrounds in the Vetti House are enchanting. You can almost hear the delicate hum created by the flight of these winged geniuses of the Pompeiian air. Elsewhere – most of the time – the picture falls to the level of poor illustration. There is something artless in the narrative of the Pompeiian paintings, and rarely do they resemble the creations of an artist. The only things that point to a great artistic tradition are the colored backgrounds and the ornament or plaster on the ceiling thermae. Compared to these, the generic mythologizing of the Pompeiian frescos seems like hackwork, the result of the whims of dilettantes.

Of all the arts, the one that most attracts the imagination here is the art of living. With growing amazement we guess after the simultaneous poverty and refinement of its everyday life, the firmness and delicacy of it. The capacity of the Pompeiians to inhabit the severe architecture of the streets and squares, which fits with their ability to relax contemplatively amid the flowers and small trees of their peristyles. A deep domestic piety and love for one’s ancestors and children exists side by side with the shamelessness of an erotic painting, an indecent priapic prank. The man of antiquity contained all this within himself without being divided against himself. His doubling was a source of natural strength, unlike our own, which is perhaps why, in the vague hope roused by so many gifts, foreigners gather at the gates of Pompeii today. As if sparks of this ancient, life-giving strength still remained in the very sun and air.

In Pompei, it takes a long time to notice that you are tired. The sight of the simple, straight, uniform streets is not fatiguing. At one point, a beautiful view revealed itself to us from the high point of the theater, the three-cornered forum. In this, the city’s southern section, the reader of Gerard de Nerval will notice, not without emotion, the small church to Isis. The dramatic religion of the East had achieved a foothold in the small Roman colony, combining in this strange way with the dramatic fate of a single poet. But this is the only dramatic spot in Pompeii. Even the catastrophic fate of the city does not seem dramatic here. It was not damned like Sodom and Gomorrah, and the souls of its inhabitants were not condemned to the torments of hell. Outside the city, on a street lined with tombs, there is one built in the shape of a semi-circular marble bench, beautifully designed by the Pompeiian Mamia, who is buried here. No small number of travelers making their way down the wide road have rested here on this bench, holding a quiet conversation, saying a good word for the dead. At these times, Mamia’s shade sits beside them, taking one of the seats on the semi-circular bench as it listens to their talk. Pompeii is full of such airy shades, and more than once the heart turns to them with gratitude; more than once it grieves with them in their empty house.

This post may contain affiliate links.