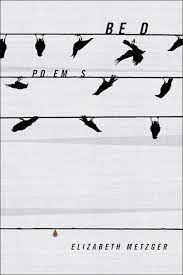

[Tupelo Press; 2021]

In the collection Bed by Elizabeth Metzger, the titular object, though largely absent, casts the entire text in its affective shadow. The bed is a liminal space that serves as a platform for disparate states “in dream and waking, in sickness and sex, in marriage and birth, in grief and death.” Etymologically, “bed” refers to “a sleeping place dug in the ground,” which suggests the grave; indeed, the bed can exist between life and death, with the occupant heading in either direction, as during curative or palliative care.

In the acknowledgements section, Metzger discloses that “the poems in Bed were written before, during, between, and after two bedridden pregnancies.” In addition, she shares that a number of the poems were composed “in memory of Max Ritvo and Lucie Brock-Broido, two great poets who continually bring me back to life even from their afterlife.” Thus, in her work, conception, birth, and new motherhood mingle with convalescence and bereavement. This postscript certainly illuminates aspects of the poems, but it would be a mistake to mine the text for specifically autobiographical experiences. Metzger’s oblique language resists such pointed dissection, which is perhaps why she is careful to mark the span of composition as “before, during, between, and after” her period of bed rest — her entire life, in other words, though orbiting these central events.

Beyond the title, the bed named as such only appears twice. In “The Witching Hour,” the speaker “would get up from bed / and be gone // with the kit of the careless.” The poem moves from past conditional to simple past tense, transitioning neatly at the midpoint, “I would have a child. / I already did.” She imagines leaving the bed and renouncing the duties of both medical and parental care, but her child snaps her back into an embedded present: “I’m a mother now.” The penultimate poem, “Desire,” opens with the line, “It is for you I put the children to bed.” The bed here is not a concrete object but part of a domestic action that triangulates commitments between speaker, partner, and child. In the rest of the book, the bed goes unmentioned, though all of the poems radiate the sort of floaty, existential thinking perfectly suited to those late-night hours when one waits endlessly for sleep to arrive.

An image that appears in the text more solidly than the bed is the door, which also shows up as a gate or threshold, and poses questions of entry, exit, access, and boundary. The first poem “Won Exit” opens,

In one or two lives

I opened the door with the prize

only to find the prize was not worth the life.I wanted the door.

The “brave mahogany door” is valued above any other object because it permits access or egress as desired. A door holds special meaning when one feels stuck or confined, a state described at the close of the poem: “In the torture of a foyer / doorless for entering, I am entering none.” The foyer or lobby, similar to a bed, is a liminal space, designed for waiting. When no escape is visible, it becomes torturously interminable.

In “Almost One,” doors appear again as a means of connection with others: “Doors don’t just open & close, / people leave them open people leave them closed.” For a relationship to deepen, both parties must leave open their respective “door.” Bed catalogs the dimensions of relationships such as parenthood and partnership but also the relationship between the living and the dead. In “Godface,” Metzger’s deceased friend Max speaks to her: “look up / that high window was made to keep you aware / of an exit you can’t access / but will be forced through.” In “this one-room world,” as Metzger refers to the living realm, doors and windows also represent enduring contact with those beyond the veil.

Related themes in Bed are enclosure and interiority, which take shape within the context of pregnancy. In “The Witching Hour,” Metzger writes of birth, “They handed him / out of my body // onto my body”; the womb is an enclosed chamber that the infant must eventually exit — for the first and last time — through birth. The spatial and emotional complexity of this experience is further explored in “Desire,” in the gut punch couplet, “The children left me. / You say they came.” Giving birth is an act of creation, but too, there is loss or grief in the transition from sharing a single body to becoming individuated. As Metzger puts it: “What could you possibly do for my body / when I am in two // separate rooms, / breathing?”

Though Bed is in part about the intimacies of motherhood and marriage, there is a lingering sense of isolation and disjunction. Intimacy, as an interpersonal project, requires one to reveal one’s inmost self to another, which can be a struggle to fully express. One of the primary functions of poetry is to convey inner experience that is lost in conventional or straightforward speech. In an interview published in The Rumpus about her debut collection The Spirit Papers, which shares several themes with Bed, Metzger says,

The more one knows another, the more curiosity is piqued, the more unknown is born — and this mirage is the engine, the abyss (and bridge) of every kind of relationship. It’s a perfect uncertainty, an emotional petri dish and a linguistic one. What can we do but babble and hope for echoes and sense, communication and communion? I’d call that poetry.

Poetry utilizes techniques often neglected in everyday language: patterns of rhythm and sound, stress and intonation, rhyme and tone, all of which evoke meaning without stating it outright. Still, language often fails, and herein lies the essential conundrum of human relation. As the final lines of the final poem “On a Clear Night” read, “No matter how much I tell you / there is as much I cannot tell you.” That is, even if one attempts to narrate every millisecond of interior thought and sensation, there will always be something omitted, elided, unspoken. However, the hermetic position of the other is also cherished, as shown in “Marriage.” Metzger writes, “You want to know what I actually love? / It is the mind I don’t have access to,” whether that be one’s own subconscious mind, the mind of the pre-verbal child, or the mind of one who has passed away.

The poem “You’ve Been on Earth So Long Already” opens with a similarly fervent wish: “All my life all I’ve wanted was to be myself / and someone else. Not theirs but them.” This is the vexing kernel of alienation at the heart of intimate affinity: though one may broach increasing degrees of closeness, one is forever alongside the other, not within. Perhaps this fact is why many of the poems in Bed address a “you” that is shifting and blurry. At different moments, “you” refers to the child, the beloved, the mourned. These relationships bleed into one another, but what remains solid is the “I” throughout, grounding the poems in a singular mindset.

The poems of Bed “use language to get beyond language” (The Rumpus) through deliberate lyricism and idiosyncratic spirituality. Metzger, by “flipping open the dictionary of myself,” generates a private lexicon to crack open the painful devotions of love and grief. The bed serves as a vantage point, a site of deep self-knowledge, and a realm of attentive care. From the perspective of one who is bedridden, riding the bed like the slowest chariot, Metzger urges the reader:

Ride the hard part,

that is the good part as many holy animals

must know and let go of,

everyone is still barely alive.

Clare Lilliston received an MFA in Creative Writing from Mills College, where they were a Community Engagement Fellow. Clare is one quarter of the writing and thinking collective Sundae Theory. Clare has work published in The Encyclopedia Project, May Day Press, MARY: A Journal of New Writing, sPARKLE & bLINK, BOMB Magazine, Cleveland Review of Books, and The Tiny.

This post may contain affiliate links.