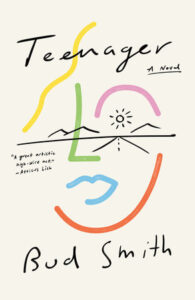

[Random House; 2022]

The world keeps turning. It’s plain to you that at the time I write this, I’m not dead. But maybe by the time you read it.

Triumph Over the Grave, Denis Johnson

There is a term, fittingly Italian — sprezzatura — that means studied carelessness. It’s when you read a book that feels like a breeze sweeping through you, but there is no doubt that the author has worked very hard pretty much forever to develop the skills to make something flow so effortlessly. This is Bud Smith. To a T.

I say fittingly Italian because Italy and the Catholic Church, which is physically seated there, hum underneath the smooth chaos of this road romance novel.

Bud Smith is the author of over a dozen works of fiction and poetry. His latest novel, Teenager, chronicles the most ancient story of all time — that of our strange existence, wrapped up in the narrative of fighting for what is right, fighting for romantic love, and fighting against the pull of death, a fight no one has yet to win.

Teenager tells the story of two New Jersey high school lovers, Kody and Teal. Teal is from a deceptively good family: she is a Catholic school educated girl, whose father molests her. Kody is a bad boy, made bad by a life of brokenness, brought up in foster care. But Kody is marked. Kody has a gift, given to him by an act of violence committed by a man named Dale, a man Kody had the misfortune of knowing in foster care, who smashed his head. Since that gift, Kody exists with a metal plate covering the smashed part of his brain, as well as epilepsy. He sees things others don’t see, feels things others don’t feel. During his epileptic fits, he uses a mouth guard to protect himself from chomping on his tongue. Like many epileptics, his visions are profound, unworldly. During these fits, “. . . God or something like God had begun to whisper to him.” Kody lives between the real and the unreal. Like the nun in Mark Salzman’s novel, Lying Awake, his visions are biblical in proportions.

The novel’s outward story, the part that takes place on this earth, begins with Kody saving Teal in an act of aggression, killing her parents, and in doing so, starts a momentum of events that are beyond their control. Before things really get under way, Kody sees a priest:

The priest said, ‘Don’t dismay. It’s a waste of spirit. Speak your pain.’

‘They told me I couldn’t join the armed forces. Any. All.’

The priest shrugged and puffed his cigar. ‘I don’t believe in violence.’

‘Oh, it’s real.’

‘I’ve always been a pacifist.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘Turn the other cheek.’

‘They had those battlefield chaplains.’

‘Not me. I’ve worked for peace my whole life. Though I have been at war.’

‘Which one?’

‘A private one. I fight it every day, every night. Against Lucifer.’

‘I don’t believe in him.’

‘Oh, he’s real.’

After killing Teal’s parents, Kody retrieves Teal, and they take off on the road trip that ends all road trips. Collateral damage happens in their quest. So does visiting Graceland, Mark Twain town, Las Vegas, and the Grand Canyon. You think it’s going to end in California, but it doesn’t.

Although I could argue that this is Kody’s story, a brave young boy trying to be a man, the narrative changes points of view throughout and breaks into Teal’s head as well. It works. Bud makes it work. When embarking on their escape, Kody “popped the trunk and gave Teal a proper explanation and exhibition of all their provisions. He hoped this demonstration would boost her confidence in their situation and she would understand they were ready to face anything together.” Then, switching to Teal, he reveals, “she was kind of embarrassed by what she saw”. And further, she realizes, “(s)he would have to help him along, delicately, lovingly.” Back and forth, the narration switches points of view, adeptly, seamlessly, making a technical feat feel as if it’s the natural way of things. In the end, it’s their story.

With nods to the Bible, Cervantes, Tristram Shandy, the movie True Romance, Chekhov, The Odyssey, and comic books, the novel also remains arm deep in the blue-collar narratives that were fashionable during Raymond Carver and Jayne Anne Phillips’ heyday. Mind you, the fashions of literature change with the wind, but books don’t. Books stay. Teenager does everything a novel should do. It’s a rollicking, hilarious story, but one where I chose to take a small break and look up words, a Dante reference once or twice, steel latticework, or how to effectively build a treehouse and make your own drinking water from rain. It’s a novel that you race through and don’t want to end. It’s fast and mean and over-the-top romantic and dark as fuck.

Teenager shreds the American dream during its long embrace. Elvis is visited and disappoints but doesn’t, the West is no longer the West. Grown-ass men tend to be horribly disappointing, usually scummy, lying frauds — and not just in New Jersey. How do we continue to believe in anything good, in the American dream, when everywhere you turn, a fresh hell smacks you down, rips away all the dreams a person can have? Is love even possible?

Toward the end of the book, when their lives and hopes and their very ideas of who they are dangle precariously, the two lovebirds have a moment:

They sat looking at each other. He gave her a rose and a tamale. He said he was sorry a thousand times. She said she was sorry ten thousand times. He said he was sorry a million times. She said she was sorry that much and a little more. He said he was sorry infinite times. She said she was sorry infinity times infinity. He said he was sorry infinity times infinity plus two.

And even later: “They made peace with each other’s faults.”

Herein lies the way to love, the how to love, the pain and shame and moving on together, through all the fresh hells. Like any good book, there are no answers to the big questions, only more questions, more pain riding alongside all that hope. But it is this sort of forgiveness in a novel propelled by a desire for human justice that gives depth to all the levity. And in that way, one answer is given to Kody and Teal’s journey, to our journey: love each other. This world is shit. All we have is each other.

Bud takes a story and makes it new, finding what is findable, the unexpected in the familiar. Boy loves Girl. Girl loves Boy. Boy saves Girl. Girl is a badass. Teamwork is everything.

What happens to our righteous outlaws, Kody and Teal? What happens when we don’t heed God’s words, “never avenge yourself”? One thing of which we can be certain is it’s also written in the Bible to “seek justice, correct oppression.” But how are we to know the difference? We are, after all, human.

Bud Smith lives in the world we all live in, on the planet Earth. But just as clearly he also lives in the private world of literature. He fosters the private existence that a reader has with a book, sitting alone somewhere, alone at home or alone in a crowd, alone on an oil rig in New Jersey, where the reader and the written word commune. He is the loneliest thing, a writers’ writer, and he is the most celebrated thing, a writer for everyone. This novel is a novel for now and a novel for all the ages. He makes it look so damn easy, as I raced through the book, soaking up all that brilliance, but that is the deception of life, of writing. It’s fucking hard. Just hold on.

Paula Bomer is the author of the novels Tante Eva and Nine Months, the story collections Inside Madeleine and Baby, and the essay collection Mystery and Mortality. Her work has appeared in Bomb Magazine, The Mississippi Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, TalkSpace, and elsewhere. Her last piece for Full Stop was an interview with Dennis Cooper. She grew up in South Bend, Indiana and has lived for over 30 years in Brooklyn.

This post may contain affiliate links.