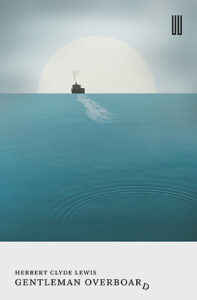

[Boiler House Press; 2021]

“When Henry Preston Standish fell headlong into the Pacific Ocean, the sun was just rising on the eastern horizon. The sea was calm as a lagoon; the weather so balmy and the breeze so gentle that a man could not help but feel gloriously sad.”

This is where it starts. The beginning of Herbert Clyde Lewis’s reissued novel Gentleman Overboard tells the end, or the near end, of its protagonist, the man named Standish, who will soon drown and sink below its flat horizons. Standish has slipped on some grease and fallen overboard. He spends the rest of the novel, and the rest of his day, treading water then floating on his back, abandoned, awaiting death, as elements of his former life are narrated on his behalf. His gaze is for the most part calm, unperturbed.

It is as if Standish views his predicament with the same cool distance of his author and creator, so that we might substitute Standish for the author, and the author for Standish. It is as though the author himself were imagining his own future death with Stoic indifference, the kind of detachment only a young man could manage—though Lewis would die young, as it turned out. As the book opens, the sun is just rising, the day is beginning, and Standish slowly realises he will not see it out.

This coolness towards his death is not merely a function of authorial distance, however. It is not an infection of the novel with the narrator’s detachment, or not only that. And this is because Standish is shown to view the world about him with similar equanimity, or flat emotion. This is something he did long before his accident. It is a point of view that extends without much disturbance into his final predicament. He only becomes frantic, he only begins to feel again, once it is far, far too late.

The journey he was making had allowed the New Yorker a short break from his life — the labours of a 1930s broker — as he travelled from Hawaii to Panama. Impoverished by the existence he once led, all Standish could manage onboard were some abstract reflections, and a few guileless words to express himself:

“The weather was perfect; that was the only word Standish could find to describe it. In fact, the ordinary superlatives sufficed for Standish in describing the trip to himself. There were things that could not be put into words, such as the colors of the sunsets, the gentle swell of the sea . . . For the rest: the cabin to which he was assigned, the food, the air, the not-too-soft bunk with its clean sheets and sweet-smelling blankets, he thought they were wonderful, marvelous, and magnificent.”

And with these words, Standish is contented. When looking to the heavens to select his lucky star, he picks the north star, simply because “it was the easiest to locate and remember.” When he considers his fellow passenger, Mrs. Benson, he finds her “remarkably fruitful” for furnishing her husband with four children in little more than four and a half years. He looks about him and sees goodness and efficiency.

On the morning of his accident, “everything was so magnificent Standish felt like a little child.” Only, the child he imagines is an artificial and hollow thing. The so-called child Standish considers himself to be is a man who has been progressively simplified, a man stripped of his faculties back to the happy simplicity of a fictitious childhood. He does not consider the reverse possibility, that Standish, the man, is actually the reverse of that. Standish represents a child stripped of all complexity and delivered to adulthood, repackaged, stupefied, so as to better endure a stupefying society. Watching Standish bob about and finally confront the nothingness of his life before the nothingness of his death has to be one of the major pleasures of the book.

The novel was first published in 1937 and would soon be forgotten alongside its author. Standish dies young, and alone, just as Herbert Clyde Lewis would himself die, young and alone, of a heart attack at age 41 in his hotel room in New York. Both men might have been rescued, neither was. A connection can be made here between the author and his creation, as if there is some kind of tragic anticipation of the author’s death in his first novel, a tragedy which is then compounded by the obscurity into which the author and his work subsequently fell. But the death of Standish does not constitute the death of a man, or the death of a fictional depiction of a man in the fullness of his being. Standish is hardly a man at all. To the extent that he resembles one, he is a man’s shadow, or he is the projection of a man on a screen, entirely level and lacking depth. Or, better still, he is the performance of a man that a man might construct for a society which requires nothing else of him but the endless acting out of his submission.

Of course, Standish represents a very specific projection of a type of man that could be more easily mocked. Standish bears the specific features of the gentleman — or a parody of it — in all its idiotic, self-regarding, and brutal composure. Yet beyond his gentlemanly traits, Standish also bears the recognisable outlines of institutional man, the man who appears to this day in meetings and board rooms and corridors, offering a superficial and compliant version of himself that brooks no surprises, that performs its own lobotomy as a condition of employment. As such, his death, as it is depicted in the novel, is not a tragic death, but a kind of non-death of a partial and contrived existence that is to be welcomed and not romantically associated with the very real, and tragic death of its author.

Ansgar Allen is the author of several books, including the novels Plague Theatre (Equus Press, 2022), and The Sick List (Boiler House Press, 2021). He is based in Sheffield, UK.

This post may contain affiliate links.