[Dorothy Press; 2022]

In October I flew east with my fiancé. I was taking H. to visit my childhood home in Concord, Georgia, population 375. My first return visit since moving to California over a decade ago. At the Hartsfield airport, we rent a Chevy and drive south, through suburbs, past the NASCAR track, car dealerships and megachurches. The churches grow smaller and smaller as we near my town. In Concord there are still dirt roads. As we drive my old bus route, H. makes jokes about Deliverance as I sing riffs from Alan Jackson’s Chattahoochee. We turn onto a paved road. My road. Pine trees and pastures flank us. “Ooooh cows!” H. said. “Can we stop for a picture?” I laugh. “What are you laughing at?” she asks. I don’t tell her that it amuses me when friends get excited at the sight of farm animals. I pull over. She snaps a picture of the pasture. In the photo, the green grass looks endless. Framed this way, the landscape is beautiful, even though I see nothing special about cows grazing or chickens pecking the earth. This is a landscape I had spent years trying to escape.

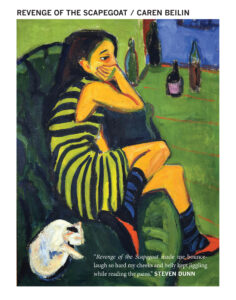

As a teen, books provided me with ample examples of how to leave. “A good book is a pamphlet on how to leave your parents,” writes Caren Beilin in her first novel The University of Pennsylvania. “A great book is longer and tells you how to leave your town.” In Beilin’s fourth and newest book, Revenge of the Scapegoat, she raises the maxim’s stakes, offering readers a surreal roadmap of how a person can escape their past without sinking into escapism.

Darkly comedic and wildly inventive, Revenge of the Scapegoat explores childhood trauma, medical exploitation, art making, and the ethics of fleeing our pasts. When we meet the novel’s narrator, Iris, she is trapped by her life. She is thirty-six, an adjunct professor, living with her addict husband in Philadelphia. She has chronic pain from rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (caused by a toxic IUD) and is estranged from her family who also live in the city. By emotionally distancing herself from them, Iris has achieved a modicum of peace. A peace that evaporates when a package arrives in the mail containing letters written by her father when Iris was a teenager, in which he blames her for the family’s many woes. Reading the letters retraumatizes Iris. Friends tell her to destroy them; instead, she leaves town.

In a borrowed Subaru, she speeds towards the country, letters in tow. But she doesn’t make it past the red oaks of New England before the car breaks down. With little money and no local contacts, she sleeps in a field. When she wakes, she’s surrounded by cows, and not just any cows, but an infamous bunch shipped over from a German concentration camp by an artist for an upcoming exhibition. As Iris soon discovers, the pasture belongs to a rural museum, the “mARTin”, owned by a murderous benefactor who ends up hiring Iris to tend to the cows.

Iris’ new job offers many perks: access to art and famous artists, a good view, and a sea of red wine to sail away on. But the job fails to provide her with the essentials she needs to survive: food, a safe place to sleep, and health insurance. When she asks her boss about lodging, she is ignored. The gallerists are busy preparing for a visit from a renowned artist and Iris’ needs are trivial by comparison. Yet, she cannot ignore her body’s needs, even if she tries. Iris bleeds and bleeds in the museum’s bathroom, which is lined with priceless art. She searches the cabinets for a tampon before eyeing a framed Picasso on the wall; she removes his sketch, wads it up and shoves it between her legs. In this droll scene, Beilin inverts a classic feminist question, asking us to consider not if a tampon can be art but if art can be a tampon. This scene is both a joke and a serious inquiry into the uses and limits of art.

Beilin’s skills as a humorist and rule breaker are on full display on every page and, as a writing instructor, Iris knows a thing or two about rules. Rules about grammar, syntax, structure. Rules that dictate what characters should and should not do in literary stories — like use the bathroom. Early in Revenge of the Scapegoat, Iris says, “I had told students . . . at the arts college, when I had posed in that teacherly manner, ‘Of course your characters have gone to the bathroom at some point, but your reader doesn’t need to know everything . . . ” Yet, many of the novel’s key scenes occur in restrooms. “The bathroom is a sanctuary to the adult scapegoat,” Iris tells us. “It’s still a holy closet, it still has that door with a lock. What a good place to gather oneself and to exhale liquid and to exhale even excrement, there is no such thing as an unlockable bathroom, not in society.” Again and again Beilin introduces cliché writing rules and then swiftly shows the reader how to subvert them.

Throughout Revenge of the Scapegoat there are few traditional transitional markers. Paragraphs, ideas, and events are tethered by Iris’ singular, addictive voice — the book is proof of the power of authorial voice to bind and drive a narrative. I zoomed through the novel, not only to discover what happens next, but more, for the thrill of living inside Iris’ mind.

While Beilin’s transgressions remind us that language is a site of infinite possibility, I was most impressed by the narrative space she gives Iris to confront her trauma. Iris flees her family, she gets far away from them. But it’s not enough. The fantasy of leaving and starting over fails her. Escapism is no longer an option, so Iris must face her trauma.

As the family scapegoat, Iris was taught that she was the source of all her family’s troubles. Her body was reduced to a receptacle, a dumping ground for their toxic run off. As an adult, Iris experiences chronic pain stemming from both family trauma and RA. The latter causes intense aching in her feet. Although an IUD triggered her RA, the larger medical community continues to disregard negative IUD experiences and tout the device’s safety. Like many women with chronic pain, Iris’s body is scapegoated by the medical industry, blamed for their mistakes and negligence. But Iris does not suffer in silence. In fact, her arthritic feet — much like her trauma — never shut up. They speak to her in the voices of Flaubert’s Bouvard and Pécuchet, and their chatter is the soundtrack of her life. A ceaseless, maddening jabbering. Here chronic pain, like trauma, is reimagined as a circular conversation from which one emerges having learned little.

Iris’ suffering does not inspire any epiphanies. Nor does her trauma guarantee her greater insight into the human condition. Beilin never uses suffering as a tool for enlightenment. Instead, she gives an honest portrait of how chronic pain and trauma shapes our daily lives, and rarely in positive ways. Rather than grand revelations, Beilin offers other narrative pleasures: surprise, delight, wonder, and connection. In the end, it is Iris’ friendships that help her process her trauma and return to the place she once fled.

It’s true that a good book tells us how to leave home, but a truly excellent book, like Revenge of the Scapegoat, also tells us how to return. Wisdom and redemption may elude us, no matter how much pain we endure, yet, like Iris, we can look elsewhere for joy, if not peace: a good conversation, a slow joke, a cup of strong coffee sipped in the sun. Iris stays alive to the world by paying full attention despite all the reasons she might want to disappear into escapism. Like all scapegoats, Iris knows that the best revenge is not triumphance but ongoingness.

At the Hartsfield airport, waiting to board my return flight to California, I drink a cafe au lait and scroll through photos of the trip on my phone. I don’t have any shots of cows, but I had a video of H. mooing at me from the bathtub of the converted farmhouse where we stayed. While H. soaked in the tub, I read interviews with Beilin on the couch as chickens grazed out the window. The video of H. mooing makes me laugh and laugh. When I put my phone in airplane mode, I find myself hating the cows a little less.

Elizabeth Hall is the author of the books I HAVE DEVOTED MY LIFE TO THE CLITORIS, a Lambda Literary Award Finalist in nonfiction, and Season of the Rat, forthcoming from Tarpaulin Sky Press in Fall 2022. Her essays have appeared in Bitch, Electric Literature, Los Angeles Review of Books, The Observer, and elsewhere.

This post may contain affiliate links.