Tr. by Penny Hueston

Marie Darrieussecq’s newly translated biography of the painter Paula Modersohn-Becker, Being Here is Everything, is a visibility project. It literally involved digging up 20 canvasses (from the basement of the Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany) for a full-scale retrospective in 2016 at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris (for which Darrieussecq wrote the catalogue). It is, in fact, a visibility project of a visibility project, as Modersohn-Becker was apparently the first female painter to paint herself naked, in 1906. More,

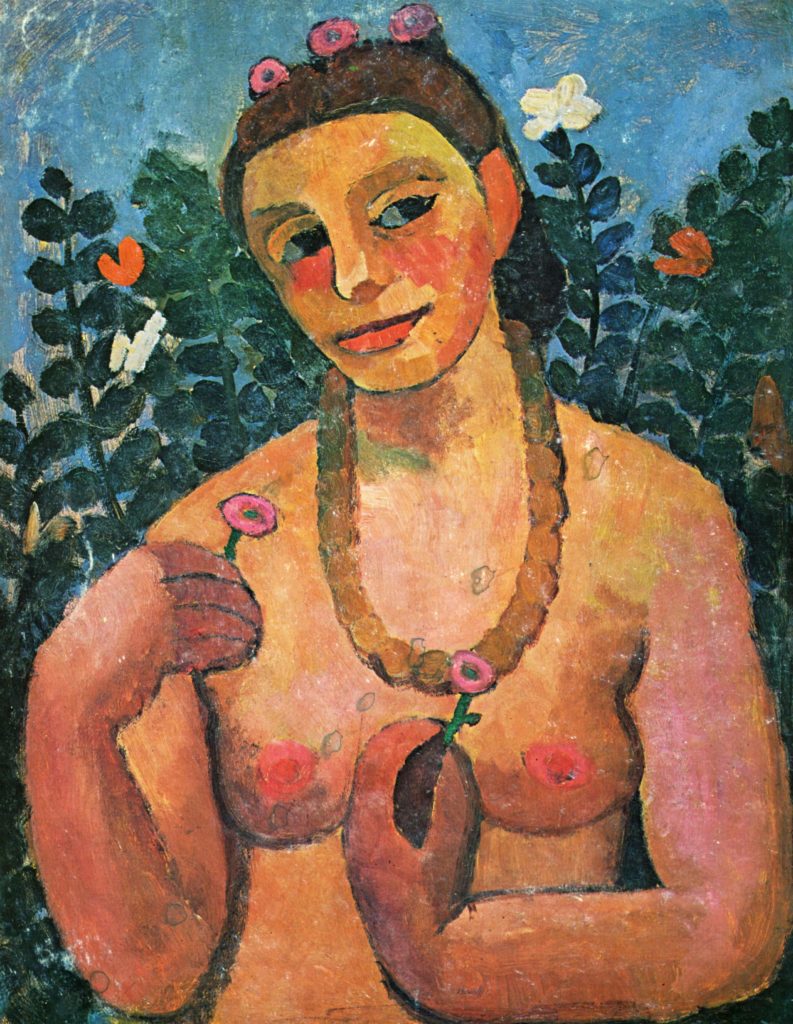

In Paula’s work there are real women. I want to say women who are naked at long last: stripped of the masculine gaze. Women who are not posing in front of a man, who are not seen through the lens of men’s desire, frustration, possessiveness, domination, aggravation. Women in the work of Modersohn-Becker’s are neither coquettish (Gervex), nor exotic (Gaughin), nor provocative (Manet), nor victims (Degas), nor distraught (Toulouse-Lautrec), nor fat (Renoir), nor colossal (Picasso), nor sculptural (Puvis de Chavannes), nor ethereal (Carolus-Duran). Nor made of “pink and white almond paste” (Cabanel, whom Zola made fun of). With Paula there is no getting even at all. No sign of rhetoric, or judgment. She shows what she sees.

The sadness of biography. How do you come to know a person whose work — not them, the work — is so singular, so spectacular and so, in its isolation, in its illest fit from all the rest, spinning into a cosmic strand so extreme, so present — they could be here, their dust is possible in you. You sadly have to come to know them in their time. A biography becomes a topography of circumstance. Oh shit. Paula writes, 1900, Worpswede, “Father wrote to me today and told me that I should look around for a job as a governess.” Shit, shit. This book must track a young adulthood to a young adult death (at 31, from an embolism soon after childbirth), as Modersohn-Becker increasingly enters, recedes, returns, leaves altogether and returns pregnant (the great stone of return) to Worpswede, Germany, in the early 20th century, and its circle of artists including a husband, Otto Modersohn. And Rilke.

“Father wrote to me today and told me that I should look around for a job as a governess,” what are you, Emily Brontë? Or a biography of any female artist reduces to the sadness of female circumstance?

She writes to her husband Otto, that successful, selling-his-paintings artist, asking for cash sounding a lot like Van Gogh who petitioned his Theo, no matter what other content of those famous letters to his brother, in the end of any letter only needing the sustenance to paint, and the paint — “As regards the order for colors. Should I remain here for another few days, please send off part of it at once. If, however, I leave in the next few days — which I hope — you can keep it in Paris,” or louder, “If, towards the end of the week, you could send me some money,” or plain, very often in the postscript, “My money won’t last me very long this time . . . ”

Paula writes, after she has left Otto even,

She thanks him for financing her trip [to Paris], and for last month’s two hundred marks, which allowed her to pay her rent and her settling-in expenses. But, if he feels obliged to help her, why doesn’t he just send her two hundred and twenty marks on the fifteenth of every month without her always having to ask him.

Van Gogh who in his indignity, poverty, and earthy humility, and in his inspired willingness to see it through, has touched me, and reminded me of Jesus — and any woman who at any given time, too, reminds me exactly of Jesus. Basement life. A life of necessary talks with the future when you are dead. A cosmic loop of desperate, necessitated, humiliated women. Indignant. Still begging men for money. Willing to talk to unformed futurities.

It is Modersohn-Becker’s willful talk to Darrieussecq that has necessitated this sad biography, this singing out of the loop, that filled me with sadness in an afternoon when I was menstruating too much. It is always too, too much. I sat there distressed, wombal and claustrophobic. This claustro-bio, full of paraphrases of all of these letters and journals, of hers, between her and Rilke (whom it has depent upon, too much, her eternity, her memory — where he in one turn memorializes her in a beautiful poem, in 1908, “And at last you saw yourself as a fruit, / you stepped out of your clothes and brought your / naked body before the mirror, and you let / yourself inside, / down to your gaze, which remained strong, and / didn’t say: This is me, instead: This is,” and in 1924 is found saying, “The last time I saw Paula Modersohn was in Paris in 1906. I didn’t know her work very well at the time, or afterwards, and I still don’t know it”).

All of these back and forths about Worpswede, getting married, staying and/or going, friendships strengthening and poofing — when art is outstanding, it’s anti-communitarian or its communiqué is with something else. It is always something else.

How can a biography of any woman not be about her sad fucking life? Of being nailed by her wrists to the kitchen, as this one was sent away to a cooking school for three months, a condition for her marriage to even proceed. When the wrist is the locus of artmaking, it is strong, the most subtle machine, it flickers delineation all over paper. How can a biography make some moves that absolutely decimate the story of what happened, the shit, shit, the always? That doesn’t nail the artist to her life? This one shines when it tries to swim in the mesmerine of the work,

She is having an affair with the sun: that is how she describes it to Clara just before their falling-out. Not the sun that divides, that shatters the image into shadows, but the sun that unifies things: low on the horizon, heavy, con- templative, as if extinguished. That’s the sun she paints: no shadow, no effects. No added meaning. No innocence lost, no virginity defiled, no female saints sacrificed. Neither discretion nor false modesty. Neither madonna nor whore. Here is a young girl: already these two words are excessive, loaded with Rilke-like reveries and with masculine poetry. These girls are saying: “Leave us alone!”

Darrieussecq writes, pretty witchy, “A meridian extends between Celan and Rilke. Meridians mark imaginary lines on the planet.” This biography witches when it extends a meridian between Modersohn-Becker and the photographer Francesca Woodman, “She wants to paint skin, fabrics, flowers: what the genius Francesca Woodman will photograph seventy years later.” I wanted, then, a multitude of more meridians, escape paths out of these letters, journals, the bio-paste, out of Worpswede, marriage, and death. Out of Rilkean orbit which I’ve learned, in my life here, will only take you so far.

I thought of the filmmaker Claire Denis, who shows women who are radiating with being as they are biking, sitting in classrooms, dancing or watching windows, a here-ness so intensely so piercingly open to variation; and of Claudia Rankine who quotes Denis in her book Citizen — “The subject of so many films is the protection of the victim, and I think, I don’t give a damn about those things. It’s not the job of films to nurse people. With what’s happening in the chemistry of love, I don’t want to be a nurse or a doctor, I just want to be an observer” — and I thought of her book Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, for the way it is a self-portrait of a woman watching television, who paints out her inundation — the pitiful things on this television — into some kind of sunset.

The sadness of biography, which is the story of a death. Modersohn-Becker’s is too soon, dead at 31 of embolism.

Eighteen days later, Paula is finally allowed to get up. A little party is organized. She asks for a mirror at the end of her bed, braids her hair into a crown, pins some roses to her housecoat. The house is overflowing with flowers and candles; everything is lit up. Paula stands, and then falls to the floor. She dies of an embolism, from lying down too long. As she collapses, she says, “Schade.” Her last word. “A pity.”

Of being told to stay down. Of the belief at that time that women would heal best if they were to marinate in their own passivity, at length.

Francesca Woodman jumped out of a window, dying in 1981 at 22. She was purportedly upset about a lack of recognition for her work. But who knows. But the death of an artist is such a kitsch button. There she is the ruddy grains of her and her blur.

Caren Beilin is a Reviews Editor at Full Stop and the author of a novel, The University of Pennsylvania, and some short fictions, Americans, Guests, or Us. She lives in Philadelphia.

This post may contain affiliate links.