[Siglio Press; 2021]

A national survey released earlier this year revealed that book reading is at its lowest ebb in three decades. Yet book sales have been on the rise for the second year in a row across nearly every category. How to explain this? Theories abound: our desire to read books is running up against our shrinking attention spans. Women, who are the majority of book readers, had their time stretched especially thin during the pandemic. But whether it was to support independent bookstores, make the most of our time indoors, or to simply feel and touch and gift physical books in an era of isolation and screens — Americans were buying books.

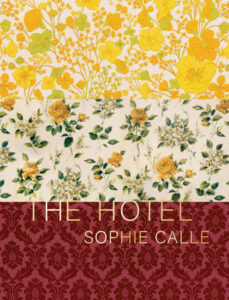

Into this slipstream falls Sophie Calle’s The Hotel. A beguiling book-object, its release was timed to the 30th anniversary of a project the artist initiated in 1981: while working as a maid at a Venice hotel, Calle made methodical notes of the personal belongings of the mostly unseen guests whose rooms she cleaned over a three-week period.

Now decades into her career, Calle is an internationally renowned artist of conceptual works whose frisson is derived partly by mashing quixotic constraints with a distinctly female sensibility. These include Suite Venitienne, in which Calle follows a man she barely knows through the streets of Venice, and a 2007 work, Take Care of Yourself, where she asked a hundred-plus women to analyze a break-up email she received from her ex (the work’s title is taken from the email’s last line). Her enduring preoccupation with the permeable line between public and private, life and art, power and vulnerability, is on full display in The Hotel.

Siglio’s redesign of the project in book form, which includes previously unpublished images, represents the first time The Hotel has been published as a stand-alone edition. The press’s 1999 Double Game, long out of print, included the project. The new edition is a gut renovation. Calle’s photographs, given more space to breathe on the page, allow our eyes to wander and rest on the possessions and private habits of visitors at the “Hotel C.” The book’s gutters are put to witty use as a natural separation between twin headboards, a repeating graphic motif.

The book feels lavish. The edges of the pages are gilded; handling its thick paper stock is pleasingly haptic, an antidote for digital content. The contrast between the black and white images, which have the forensic quality of crime scene photos, and the full-color spreads is as eruptive as the transition to Technicolor in The Wizard of Oz. The color images are rapturous, even lurid. The Baroque, maximally floral patterns on the bedspreads appear to crawl upward and outward into the equally ornate wallpaper. It’s Dario Argento meets Laura Ashley.

Another fruitful study in contrasts: Calle’s brisk, deadpan documentation style and the tenderness we come to feel for the unseen hotel guests whose privacy we violate. Here’s a typical accounting from Calle: “Two pairs of boots (sizes 38 and 42) have appeared. The suitcases are still locked shut. The three pairs of underwear have not moved.” Meanwhile, her photographer’s eye reveals an intimate portrait of the bodily depredations we hide from the public eye — the pimple cream, the foot cream, suppositories for constipation, menstrual-stained panties, and even the bottom half of a pair of dentures. (Did the owner leave the hotel wearing an extra set?)

Rummaging through suitcases, opening drawers, and arranging the contents of toiletry kits and handbags for her snapshots, the artist is both there and not there, never seen but far from invisible. She steals from a box of chocolates. She retrieves a pair of shoes from the wastebasket for herself. She reads people’s diaries, which, on its face, seems especially scandalous, until it becomes clear the entries are universally banal. Despite her clinical approach, Calle does not pretend to objectivity. Certain guests bore her: a Swiss family with two children, whose luggage she can’t be bothered to snoop through. A pajama bottom described as “lying stupidly” on a chair strikes her as “obscene.” Other guests, usually solitary travelers, incite her imagination. When the guest in Room 25, a reader of Somerset Maugham and partial to tweeds, checks out, she notes wistfully, “I shall miss him.”

With Calle as our guide, we, too, become active voyeurs, joining her in the practice of drawing conclusions based on an economy of evidence. A man, traveling solo, checks into Room 30. In the drawer of the nightstand is a wallet containing five photographs of a blonde woman, including a wedding picture of her and her husband, the guest in Room 30. Something else: an old bill from the Hotel C, dated March 4, 1979, for the same room, exactly two years ago. He has packed a woman’s embroidered nightgown, which he drapes over a chair. His reservation was for one night only. The project invites, in revealing gaps of unknowingness, space for us to inject our own speculative fictions.

To experience the project thirty years after its inception is to be voyeurs of another kind: as witnesses to the passage of time. The objects Calle finds in the rooms and the decor of the rooms themselves now present, for contemporary audiences, careless evidence of life in the early aughts. A couple who Calle overhears having sex have brought with them a Sony Walkman — one that plays cassette tapes. (They’re fans of Bernard Lavilliers and The Doors.) The ubiquity of postcards reminds us of their practical function before smartphones made the sharing of photos instantaneous. There are no wheels attached to any of the luggage.

By the third and final week of Calle’s project, the rooms, their inhabitants, and her shifts have begun to “all run together” in her mind. The project is turning into a job; it’s her signal to leave. The artist had collected all the material she needed for her project, one we can now hold in our hands in the shape of a book, the very thing-ness of which calls to mind Station Eleven (and its recent HBO adaptation). In Emily St. John Mandel’s post-apocalyptic pandemic novel, the plot turns on a self-published comic book of which only two copies survive. The comic, read and reread to the point of tatters, functions as a totem and cultural relic of the “before times,” as well as a divining rod for an uncertain future. Its magical allure is unabated, unlike the electronic artifacts (cell phones, laptops, and the like) entombed in the “Museum of Civilization,” gone dark without the animating Frankenjuice of the internet.

As St. John Mandel’s novel suggests, social order may collapse, but art will persist. Years after its making, The Hotel remains infused with Calle’s visual flare and her canny sense for mystery and suspended narrative. Both are distilled in an image of a cheap plastic comb with broken teeth left on the lip of a sink or the toes of a pair of women’s flats stuffed with paper to retain their shape. The jumble of an unmade bed evokes the writer and photographer Teju Cole’s lovely description of folded drapery as “cloth thinking about itself.”

Appraisals of Calle’s oeuvre frequently discuss the role of surveillance. The Hotel fits easily into these concerns. I could, for example, go on about how officials in Venice, in an effort to contain overtourism, have installed hundreds of CCTV cameras and have begun using tourists’ cell phone data to catch day trippers who overstay their welcome. But the project’s most striking provocation in the context of the now has to do with the dynamics of leisure and labor.

The hospitality industry tanked during the first year of the pandemic as tourism came to a near standstill. And while the industry has since rebounded from its lowest peak, aspects of its workforce may be radically altered forever. In a jiujitsu profit-hiking move, executives at the major hotel chains have announced plans to make daily room cleaning a thing of the past. Hotel cleaners have already seen their shifts reduced; an estimated 181,000 cleaning jobs (or about 39 percent of the hotel cleaning workforce) stand to be permanently erased. Unlike Calle, the women — and they are overwhelmingly women — who fill these jobs need the work. The pandemic, in addition to exposing the fault line between essential and non-essential workers, shone a laser on the crater that is the inequality gap. If Calle’s project were to be performed today, would our attention be tuned as much to the people who change the beds as the people who sleep in them? These gilded pages might take on another meaning, and we the audience, the kind of people capable of dropping forty dollars for an art book, would perhaps perceive ourselves more clearly on one side of a dividing line.

And yet I’d still want the book.

Lisa Hsiao Chen is the author of Activities of Daily Living (W.W. Norton) and lives in Brooklyn.

This post may contain affiliate links.