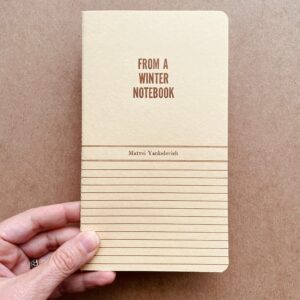

[Alder & Frankia; 2021]

Matvei Yankelevich’s chapbook From A Winter Notebook explores the solitude and introspection that come with the season, themes that feel particularly poignant in the midst of another pandemic winter, a rubbery, time-warped period marked by both uncertainty and stasis. In sonically rich “unplain cant” as Yankelevich describes it, these poems probe memory, desire, domesticity, and the creative process itself.

This limited-run letterpress edition uses vintage lined and gridded paper to mimic the appearance of a notebook. The form suggests an inherently personal object, a receptacle for one’s musings and observations, and thus establishes a sense of intimacy or even voyeurism. The reader peers through the language to catch a glimpse of consciousness in motion. Yankelevich’s tone is conversational, but it’s a conversation turned inwards. The title gestures toward the gap between private record and public manuscript: the poems are “from” a winter notebook, which suggests the existence of an actual notebook containing many more poems that were ultimately excised to foreground this brief series. The negative space of the unpublished winter poems looms off-page. Though the speaker claims “I need not publish this, / just throw it,” the fact that these compositions have been carefully selected highlights the artifice of the gesture and enacts an interplay between curation and confession.

Each poem begins with winter, producing a shifting refrain that matches the repetitive nature of the season’s dark and short days: “It is winter,” “It’s winter,” “Is winter,” “In winter,” “Winter,” and “It is still winter . . .” Winter is sluggish, laborious, gestational in a way that can feel stuck on the threshold. Winter is for hermitism and hibernation. Despite the freeze, the mind is always there, thawing and dripping, characterized by self-awareness and a bitter, self-effacing wit: “It’s winter and someone is writing the same / poem as I am with better penmanship, / in pencil.” The speaker, operating from within the “same office of winter poems,” catalogues a melancholic tautological cycle where perpetually “it’s winter because it’s winter.” The friction against winter as constraint both shapes and animates the work.

The backdrop for these poems is markedly domestic and mundane: the “dom-dom-dom [that] is home.” There are desks and kettles and dirty dishes; there are vitamins and glasses of wine. Home becomes a sort of limbo, a liminal space, where “books I can neither shelve / nor open await me on the unmade bed.” In this setting, the self, too, can be undone, at loose ends. Though one might imagine winter poems would focus on natural scenes of snow falling across evergreen trees, Yankelevich instead gives careful descriptive attention to the detritus of the home-space. Everyday disarray is transformed into an aesthetic tableau. For example, in the opening poem, “Fat brown bug greets me / at the door — who knows how long it’s been / half dead (or full dead, for that matter): / now from dust pan to flushing gutter.” Through the assonance of “bug,” “dust,” “flushing,” “gutter,” the insect becomes a poetic object imbued with symbolic energy, reflecting the speaker’s own “half dead” torpor.

Under this roof, the alternate meaning of “dwelling” rises to the surface as the speaker lingers in thought and memory. Lost love haunts the lines: “Whose / ghost will look over my shoulder now / as I’m shaving?” Following the Romantic tradition that centers an interior emotional landscape, longing is laid bare “to desire desire.” The speaker seeks a spark, a motivating energy. Though he proclaims, “I’ve been good and / slept alone and not been touched by / anything,” the ascetic impulse to “be less” is countered by bodily appetite: “In my mind, I’m touching your / haughty knee . . .” These tensions — between physical and mental, between excess and lack, between indulgence and abstention — enliven poems that may otherwise be consumed by inertia.

The last lines of the final poem in particular express the strain between mind and body:

because by the time I take off my coat,

whip off my winding scarf, remember of

my vest, zip out, find a seat for a hat,

untie and unlace and pull off the boots,

grope the light, bear down on the notebook, note

the warmth, grapple a pen to uncap it,

the poem part of the poem is gone.

Here, the verbs (“grope,” “bear down,” “grapple”) are visceral, nearly violent. The writer must forcibly wrestle the poem onto the page, as the physical act of writing can’t keep up with the speed or ephemerality of thought. “The poem part of the poem” is shifty, arriving as a flicker and lost just as quickly. Yankelevich exposes the drudgeries of the writing process, from revision (“it took / all year to edit this sentence,” “it’s tough to be a sentence in / winter”), to typeface (“trouble choosing between Gill Sans and / Perpetua”). Still, “the poem’s busy brain” shines through, operating by wordplay, “slant speech,” fits and starts, m-dashes, and ellipses. Mobility arises as the staid grammatical unit of the sentence, “diagrammed, disconnected,” gives way to line and break.

Yankelevich’s larger project continues in the chapbook Dead Winter (Fonograf Editions, 2022), in which he expands his canon of winter poems to tackle thorny topics briefly touched on in From A Winter Notebook regarding literary community, lyric tradition, and identity. Through the wide and capacious frame of winter, both texts find “a way to begin,” and despite the “exhaust and exhaustion,” trudge onward through the slush.

Clare Lilliston received an MFA in Creative Writing from Mills College, where they were a Community Engagement Fellow. Clare is one quarter of the writing and thinking collective Sundae Theory. Clare has work published in The Encyclopedia Project, May Day Press, MARY: A Journal of New Writing, sPARKLE & bLINK, BOMB Magazine, Cleveland Review of Books, and The Tiny.

This post may contain affiliate links.