[Tupelo Press; 2022]

My wife and I were in Best Buy recently, looking for a new refrigerator. The last time we had bought one was 25 years earlier, and what we wanted as a replacement was a replicant of our old model or close to it: freezer, main compartment, two drawers on the bottom, butter box on the side. No frills, no fancy stuff, not even an ice cube maker, just an honest American refrigerator like one George Washington would have had if there had been electricity in his day.

Such a model wasn’t to be found. I knew something was up when I saw a label on one fridge saying, “Wi-Fi enabled,” and when I asked Tate, the friendly Best Buy salesman, what that meant, he replied, “Oh, you just download the app, and then you can do things like change the temperature from your phone. You don’t even have to be in the same room!”

Happily, I’d been reading the elegant, demanding, and well-wrought poems in Corey Van Landingham’s Love Letter to Who Owns the Heavens in the days before our Best Buy visit, so I felt right at home in Tate’s world of superconductors and integrated circuits. “Darling, we are such sweet modern machines / when our parts are working,” says the poet in her book’s first poem. [unnumbered page] And so it goes all the way through to the last page as we are guided by a speaker who is both flesh and blood, wires and microchips.

This is nothing new, of course. In the classical sense, a poem is a machine, a thing of rhyme and meter that produces thoughts and feelings. What Van Landingham does is provide us with this year’s model. Poetry classes being what they are, most of my undergraduate students are young women. I have the feeling that many of these will want to be someone very much like Corey Van Landingham one of these days, so I’ll show them this book both for its individual poems as well as its ambition, its gathering of ideas and images from everywhere to create a storehouse whose inventory is both finite and inexhaustible.

Most likely I will start with “Kiss Cam,” in which a woman buying a pretzel at a ball game sprints back to her seat in hopes that the camera will find her in the crowd and put her face up on the Jumbotron. Every type of spectator has been there already: “the reluctant husband, / holding out until the final second / for an automatic peck,” then “the graying couple / really going at it, tongue and all,” and finally the young parents who’ll find themselves “twenty-nine forever” in the photo that will be waiting for them at Gate 4. Admit it, says the speaker to the reader—you want this, too. But in its last three lines, the poem takes a gothic turn: “You want to be the woman / bursting onto the screen alone / while the stadium around her burns.” [19]

Hold on there! This isn’t rosy-cheeked Americana, after all, this isn’t hot dogs and apple pie but a scene out of a Stephen King novel. You can almost hear the screams. The poem begins with a woman jonesing for a pretzel and then ends with her bringing down her world as surely as Carrie destroys her school gym in the movie of that name.

Do I detect a critique of capitalism here, a critique of myself? I’ll admit to the sting: like most people these days, I enjoy my creature comforts even as I shake my head ruefully while the polar bear glides past my window on his melting slab. To paraphrase Charles Dudley Warner, everybody talks about what’s happening, but nobody does anything about it. At least the poets—at least this poet—describe what’s happening in terms that are harder to ignore.

We’re getting ahead and getting behind at the same time, says Van Landingham: yes, the transcontinental phone line was finished in 1914, but eleven days later, “Franz and Sophie were shot in Serbia,” she says in another poem, “and the world was dark for four more years.” [12]

The poem that captures the present plight best is a fourteen-pager called “Cyclorama,” itself the middle part of a triptych in which the voices of visitors to the Gettysburg battle site weave in and out, mixing their obvious observations (“I would have shot the prisoners instead”) with the insightful. [46] Till recently, the Civil War seemed fixed in the past; now it looks as though it might happen all over again. To the visitors who seem to be learning about that conflict for the first time, that past could be their future, not in spite of but because of them. We are doing it to ourselves. It is we who own the heavens, and we are not doing a very good job of taking care of them.

Remember, though, that this book is, as its title says, a love letter to us bumbling custodians. There is none of that irritating consistency here that mars so many collections these days; instead, that sexy cyborg of a speaker flits in and out, powering up and falling away exhausted and then popping back in when we least expect her. In that way, she reminds us that, if we have the ability to screw things up, we also have the power to make them right again.

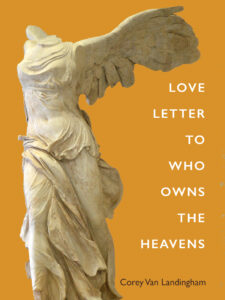

To use two images that recur throughout, that speaker flies like a drone raining down firepower but also like Nike, the goddess depicted on the book’s cover. I looked up Nike in the Encyclopedia Britannica to see what she is capable of, and there it says she is the goddess of victory in war, sure, but also of success “in all undertakings. Indeed, Nike gradually came to be recognized as a sort of mediator of success between gods and men.”

The takeaway? Nike presides over the world, then and now, and this poet is her messenger.

David Kirby teaches at Florida State University. His collection The House on Boulevard St.: New and Selected Poems was a finalist for both the National Book Award and Canada’s Griffin Poetry Prize. He is the author of Little Richard: The Birth of Rock ‘n’ Roll, which the Times Literary Supplement of London called “a hymn of praise to the emancipatory power of nonsense” and was named one of Booklist’s Top 10 Black History Non-Fiction Books of 2010. His latest books are a poetry collection, Help Me, Information, and a textbook modestly entitled The Knowledge: Where Poems Come From and How to Write Them.

This post may contain affiliate links.