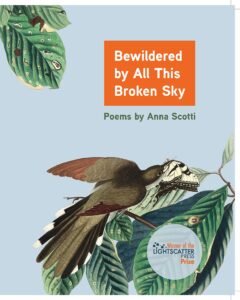

[Lightscatter Press; 2021]

In Anna Scotti’s debut poetry collection, Bewildered by All This Broken Sky, the 405 freeway is “a fitting memorial to quiet disaster.” This feels in keeping with a predominant view of Los Angeles: driving these freeways can create a sense of a city so randomly laid out as to feel devoid of history or even forethought. There is something cruel about this vision. But also something rife with promise:

Believe

in magic here, in substance wrought of smoke, in life,

then no life. The freeway is a made thing, a patched fabric

stretched taut between exhausted mountains, but it’s alive

in ways you’ve never been, vibrating in time with the engines and

the cries of birds and chainsaws. Those spent hills,

dull with chaparral and painted concrete,

are marked with tattered bouquets and letters made

more fearfully than lives are made, and lost.

This tonal shift is signature of Scotti’s poetry. Her collection is alive to quiet disaster, to pain and suffering and the apathetic way our lives shake out, while also able to embrace their randomness, the joy and wonder available if we dig deep enough and insist on it. Not to mention that finding joy in the midst of chaos and cruelty is our only option. As Scotti writes, “Rushing past you think of stopping, of — what, then? You’ve no means to put an end to it, only tires.”

Full disclosure: the author of this collection was my fifth-grade writing teacher and early inspiration, the reason my ten-year-old ramblings were praised and encouraged rather than used as fodder for referral to a child psychiatrist. In the years that followed my time as her student, Scotti ran a Sunday afternoon writing group for her most devoted acolytes. We’d sit in her living room, a group of ragtag middle schoolers on the verge of something, trying to out magic each other with brief sprints of writing, laughing, and eating popcorn, keeping our pencils moving at all costs. The joy is what I remember most — the unselfconscious way we reveled in our work and of course the giddy feeling, afterwards, of driving down Olympic Boulevard in the backseat of my dad’s car having made Anna laugh with something I wrote.

That joy and magic are on full display in Bewildered by All This Broken Sky, a collection that spans over a decade of Scotti’s poetry. These poems are intricately constructed and cover a remarkable amount of ground. Their scope is what sets them apart, as well as Scotti’s capacity for adept and surprising description: earthworms after a storm, “forced from bloated soil to sizzling brick,” are no more than “muscular strips of suffering.” Or as demonstrated in a bus ride remembered from childhood:

— Wednesday nights we’d board the groaning city bus

pushing past the weary workers coming home as we

were going out, three girls in prim dresses and white socks,

two boys chafing against starched collars.

At Society Headquarters we were all in a line like wild

ducks, like materyoshka, like Appalachian measuring cups,

filing neatly toward our usual row of grey metal folding chairs,

already lost in chimpanzee dreams,

grubs on sticks, smelted iron and gandydancers,

then a bus ride home in the deepening dark, drowsy now

between my brothers, just a girl again. Quarters tinkled

in a metal box beside the scowling driver whose bristled

neck rolled over his collar in grubby yellow folds.

I recommend sitting back and letting these poems sweep you along: read this collection in a single sitting, cover to cover like I did, and then go back to the beginning to savor it more slowly. Notice the ways life is celebrated, mourned, then celebrated again. Come away guaranteed to find the fine hairs on your arms at full mast.

Take “Twelve,” for instance. A woman reflects on her daughter as she’s perched on the verge of adolescence but still engaged in childhood rituals of nurture and discovery: “gathering worms after every rainfall, laying countless broken birds to rest in tissued boxes, grim as any village preacher.” She then projects a future in which her daughter has a daughter of her own: “There will be a boy who does not love you, then a man. And someday, a child, willful as a windborne spirit” one moment and “curled in a sullen circle of music, friends and secrets that exclude you” the next. The poem then jumps forward again, into a future where the speaker is but “a photograph on the dresser, a folded note beneath a stack of silken scarves.” And ends with the following note, culled from the speaker’s own experience and propelled by her need to leave her daughter with a roadmap to handle her life once she’s gone: “Don’t flinch in the face of all that angry beauty; breathe. Know what it is to have love enough to squander.”

All that angry beauty before which all we can do is breathe. Pause, then take stock. Sage advice. These poems will have you believe that rarely is anything as serious or fatal as we might think, even our most shameful or selfish moments. If I had to name the guiding ethos of the collection: “Very little you can do or say will shock the god of self-indulgence.”

With that straightened out, we can return to the messy business of motherhood and daughterhood, girlhood and growing up, and rejoice in all that’s wonderful and absurd about it. The revelations of these poems unravel slowly: their speakers often reflect on the paths of their lives from a vantage point far enough removed to be sanguine about the whole ordeal of living. You will make mistakes, you will be the “bitter-hearted miser counting others’ sins.” You will inevitably find yourself lying awake, taking account of all the ways you’ve erred, the needless pettiness you wish you could take back: “. . . the storekeeper you teased, then cheated, even the exhausted salesgirl you cursed and hung up on.” You will look critically at yourself and find yourself wanting, as we all do.

Nevertheless, there’s a comfort to these poems. These moments can haunt a person, but loving and being loved in return can offer us some exoneration: “Remember the time you wished your grandmother dead? She died, of course, and now she’s in heaven waiting to laugh it off and serve you a steaming plate of baked lasagna or some homemade raisin bread.”

And if not exoneration, then at least understanding, accrued over decades of life lived, softening the edges we develop in youth, the snap judgments we make of others:

So many summers ago that I doubt you are alive to recognize yourself, the old Galahad of my poem — but let’s start with the baby, pushing her own stroller with far starfish hands, while you, sullen neighbor of drawn drapes and noise complaints, carried a bag of trash as tidy and neatly knotted as yourself, frowning as if even a sour nod might cost you [. . .] Now that I have known loss, I know what you wished to spare us. Now that my bones ache, I know what that leap cost you, and the reckoning: my daughter’s bright sharp laugh, my pretty hand extended as you sprawled, cursing, casting shadows in the drive.

These poems make evident that this kind of boundless love — love we take care of, love we’re sure to name as such — is the key, the only real salvation available. This collection is generous with our least generous human impulses, and if you’re trying to navigate the world in 2022, I’m guessing you could use a little generosity.

What do we want poetry to do? Raise the hair on our arms, maybe make us pause frequently to look out the window, perhaps reflect the world back to us in a way that makes apparent the full scope of our emotional experience. And also, if we’re lucky and it’s that kind of poetry, make us keep striving for joy. These poems do it all.

Eva Dunsky is a writer, teacher, and translator. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Joyland, The Los Angeles Review, and Cosmonauts Avenue, among others, and she’s at work on a novel. Read more of her writing at https://evaduns.ky/.

This post may contain affiliate links.