Confession: I’ve never actually met Bill Lessard. Yet, over the past 4 or 5 years that we’ve corresponded and interacted online, I’ve come to consider him one of the most vital and necessary presences in my life. His strong aesthetic commitments have much to do with this, but so does his generosity. I know I have benefited directly from him telling me, with his customary verve, “this is what’s up” in the realms of literature, cinema, music, and, well, thought in general.

Although we have spoken casually about each other’s work prior to the interview recorded below, the publication of Bill’s beautiful, uncannily heartbreaking instrument for distributed empathy monetization (Kernpunkt Press) finally gave us an occasion to transparentize and concretize some assumptions — about poetic modes, about experimentation, about choice (and freedom thereof), about what’s most Inferno-like about our contemporary hellscape, and about the historical — that have guided our more casual conversations. As usual, Bill’s remarks sparkle with trenchant wit and genuine curiosity. Reading through them again, I can only look forward to our next encounter, whatever form it takes.

Joe Milazzo: Maybe I should start at the beginning. That is, by asking you about the origins of instrument for distributed empathy monetization. I’d be curious to know how much of the writing, if any, preceded the graphic component; that is, how much of the sourcing of images came first?

William Lessard: My work is about the pursuit of 21st-century forms. Literary forms, from the sonnet to the novel, all are rooted in the past. So, to be a good futurist, I’m trying to do the opposite. I’m asking: “Well, what are some of the unique forms to our contemporary world?”

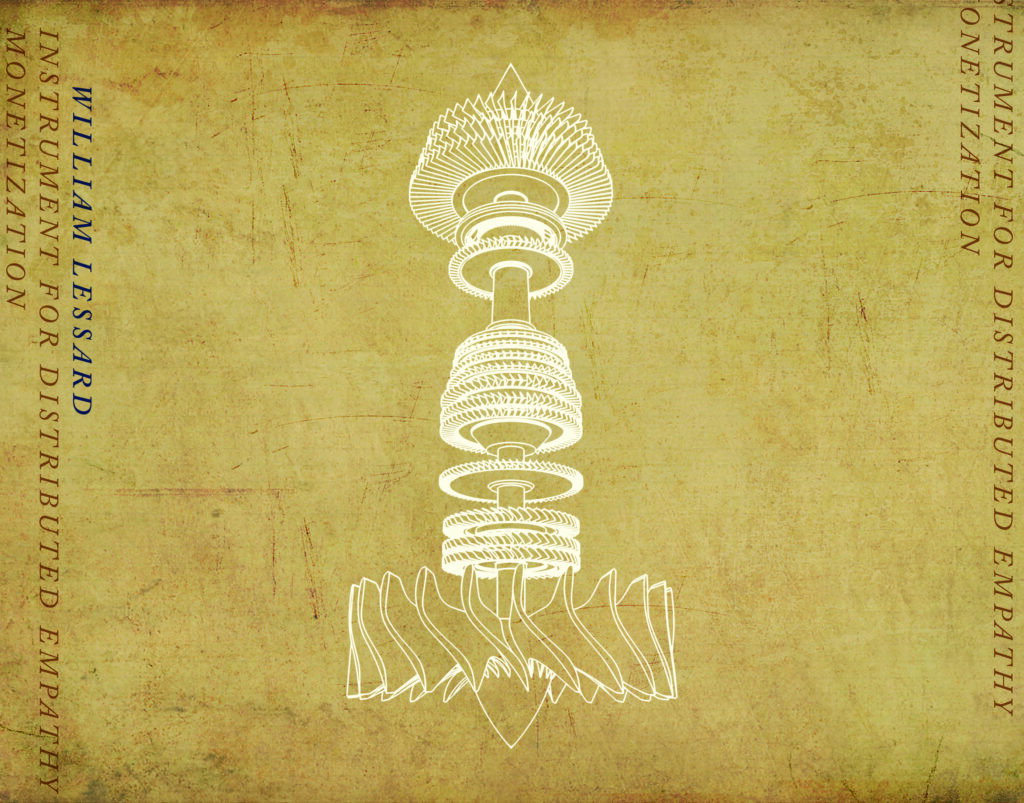

This series originated from a corporate empathy template I bought. I replaced all the boilerplate language in it with the most contrarian language I could imagine. Surrealistic, Dada, whatever you want to call it. I also created that central graphic based on the template, then wrote around it and around it and around it. I never intended to create a chapbook or anything. I was just filling in spaces within this template. Eventually, it took on this life of its own as a handbook for creating corporate subjectivity. Which, ultimately, is also a simulation of how corporations fail at empathy but become sentient because of that failure.

I have and frequently struggle with a similar desire: to work in a subversive mode. But how much of subverting is also “leaning in,” as we like to say? Do you see a distinction between the two? Or, what sort of relationship binds subverting and leaning in?

All art is product, and all product is art. To some extent, no one is outside the process. The book itself will be available for purchase. So it cannot escape—and maybe doesn’t want to escape—the system that it criticizes. But, within its own system, it fails. And maybe it’s meant to fail. There’s no one-to-one correspondence here. Everything moves towards the funnel, right? (That’s something you and I understand from our day jobs[1].) Everything is about the funnel. Whether you see the funnel or not, the funnel is always there. The funnel is where the customer enters the process of conversion. But who is being converted?

So, this chapbook is also about how the broken mechanism is functional. But it would have to be unbroken in order to be a true capitalist product. To me, that’s the nuance. That’s the tiny gap between subverting and leaning in.

So, would you agree that poetry can safely handle certain toxic materials? That poetry allows us to approach, handle, and even experiment with their toxicities?

I do. Because you need to understand what makes those things specifically toxic. You can’t just trust assumptions. That’s why so much contemporary poetry sucks. Poets are still writing like 19th-century farmers. They’re so morally revolted by their political opponents that they’re literally off in the weeds.

Yes, how much contemporary poetry is motivated by fear?

For so many poets, it’s less about fear than privilege. Their economic privilege frees them from having to mess with these things and this language. They can remain morally pure. Whereas we have to work for a living and have to cope with it.

It’s an interesting sort of quandary. “Poetry is news that stays news,” or so Pound’s edict goes. (And is it inherently fascistic?) But the closer we kind of get to the event horizon of the contemporary, the more poetic establishments (for lack of a better term) seem to want to look away from how the present expresses itself. They won’t even approach it like Perseus does Medusa.

You know, they hate this stuff. And I think it’s mostly like you said, it’s morally repugnant to them; it violates certain aesthetic categories. I think it’s also embarrassing in a way that they —and you, and I, in part—want to look away. But we don’t retire to our fainting couch.

Those notions of embarrassment and shame—I think they’re really operative in your book.

If you’re going to talk about empathy, you’re also going to have to talk about shame and embarrassment and a whole range of negative emotions.

Emotions that, as a culture, we want to manage. Which is to say we want to productize or merchandise them.

We want the data points, baby.

But quantifying these feelings is about concretizing them, and concretizing them is about shunning them more effectively, no? How can you consign something that’s nebulous or “purely” subjective: qualia? So, really, self-help culture—which is all American culture, in many ways—is not concerned with reckoning with these emotions so much as it is invested in pathologizing them. So that we can then apply the proper treatments and correctives.

Right, so we can figure out the correct medication and the correct dosage.

Nevertheless, there’s this question of evolution, I suppose. Maybe all our feelings are maladaptations. Even so, they’re inextricable from our mode of existence. To bring it back to what you observed earlier: the failure to empathize is probably the most human thing ever. But there’s some strange utility in that failure, one that potentially unplugs us from capitalist systems, or the way we live now. I’m thinking particularly about when the language in instrument for distributed empathy monetization becomes recognizably (classically?) poignant. When that occurs, the book really throws me back into myself and makes me think about the negative—or, to lean in, “unproductive”—emotions to which I am subject and the way I conform or refuse to conform my subjectivity to them. We’re not talking about Keats here, but I also can’t help but think of negative capability in this context. Do you find that a meaningful or helpful concept in thinking about your own work?

I try to find poetry in anything. And to give that poetic quality a certain swing, to use jazz terminology. I’m a big fan of Eva Hesse. Eva, like a lot of the artists of her time, would trawl around Canal Street, picking up wires and tubes and other discarded objects of mid-century manufacturing. And then she would arrange them in very expressionistic ways. So, she can make a piece that mostly looks like a jumble of wires, but, looking at it, you can feel her anxiety. That’s the kind of emotiveness I’m trying to infuse into this really absurd material, frankly, Instead of like trawling around on Canal Street, I trawl around online: Google Patents, Google Scholar.

It’s worth thinking about how some of the most prolific authors of our time are corporations.

Corporations are people now. That’s accepted knowledge. So, if corporations are people, what are people? Are people corporations?

There’s a corporate aspect to the person, certainly. There’s the theory that our organs were once independent organisms that somehow decided to get together, to cooperate and create a new entity.

Yes, we have to talk about specialization with the human body as well as within the corporation. And the rise of corporate intelligence has changed that conversation. All the data that we wrap ourselves in… it’s almost as if each of us is a publicly traded corporation. Some sort of stock ticker is constantly reporting our value. And not just our credit scores, although that’s one example. Look at what’s happening in China with social scoring. It’s coming here. It’s already here; it just operates under a different name.

I receive automated emails — I don’t know how I started getting them, but they come to an email account that I use to harvest spam, etc. And I get these emails from some outfit, the name of which I can’t remember, constantly warning me about my social reputation. They’re running some sort of proprietary algorithm on public information.

So, basically, every time you post a conceptual poem, your score goes down.

I would think so! What’s also interesting is that they’re looking at people who are connected to me in some way. So, if I have a relative or even a neighbor who makes the news, for reasons that they probably shouldn’t, that’s affecting my score. So I guess I can be reviewed just like any business on Google.

Again, if corporations are people, what are people? Are people just dysfunctional organizations at war with other dysfunctional organizations? Constellations of data around choices made and reputation earned and all that stuff — that makes up the self in the digital age. So I put the corporation at the center of a lyric poem instead of a person.

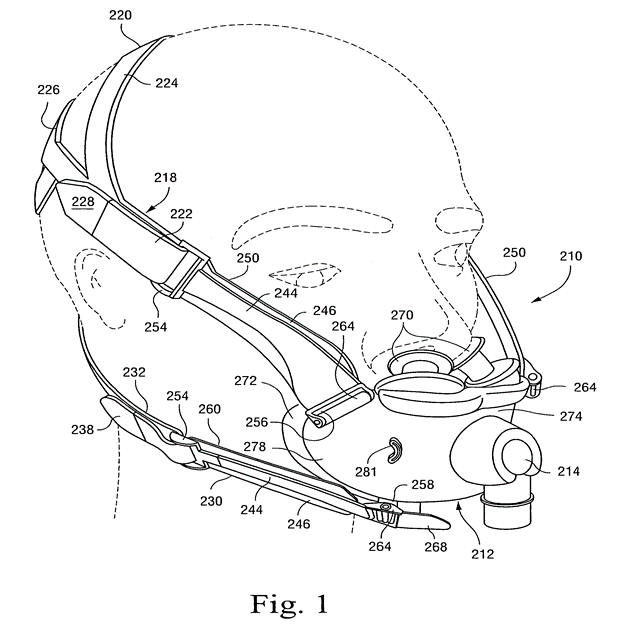

Tell me something more about the first image we encounter in the text. It looks like a rendering of a CPAP machine from a technical manual.

It is, or it’s a device related to a CPAP. I found it on Google Patents.

Out of context, it could be a torture device.

It could be any number of things.

It got me thinking about what the point of the patent drawing is. It’s about intellectual property, of course. The person is only there for demonstration purposes. Right? So of course they’re transformed into a kind of mannequin or phantom; they’re literally constituted by dotted lines.

That’s right. Yet this rendering of the person is so normalized. Especially if you look at patents all the time.

And whether one has never been exposed to patents in that capacity or not, how they function still influences you and the world through which you’re moving. And in this patent, if it is for a CPAP machine: the drawing is ostensibly demonstrating how one can draw breath through the instrument. But, in reality, to make that happen, the machine has to force air into your nose and throat.

Yes, it’s smothering you and taking your air. I also say I chose this image because it shows a figure prevented from speaking. They’re gagged. Which is a way to signal to the reader that the voice in the book is not the voice of the individual. It’s the voice of the corporation ventriloquizing the individual. At one level, instrument for distributed empathy monetization is the dream of personhood dreamed by a corporation. But I have news for those corporations. It’s not so great to be a person.

Where does that leave me, the person reading this text and occupying this dream, at the end?

Well, one reader told me that the ending is very Baudelaire. And my response was, “Yeah, it is very Baudelaire, very Le Spleen de Paris.” At least, I felt those poems hovering right over my shoulder as I wrote toward the end.

I kind of thought of it as Eliot’s Fifth Quartet. It has an elegiac quality, but also a strange energy.

It’s an elegy someone’s turned a blowtorch on.

I can see that. It’s also risking something: to end on what could be construed as the most conventionally poetic expression in the book.

Or the lyric poem you’ve just read continues, but you’re not privy to it. I hope there’s a sense of risk involved in spurring a desire to read more—a sense of emotional danger. What will this consciousness attempt next? You can write the most politically progressive piece in the world, but it’s not going to matter if there’s no stakes involved. A white canvas, you know, a cube. Big deal. The reader is not going to care unless they feel you are putting yourself at risk. It’s reciprocal. They care. But the work must first care about them. Like any good corporation.

Joe Milazzo is the author of Crepuscule W/ Nellie, The Habiliments, and Of All Places In This Place Of All Places. His writings have appeared in Black Warrior Review, BOMB, Full Stop, Prelude, Tammy, and elsewhere. He is also the Founder and Editor-In-Chief of Surveyor Books. Joe lives and works in Dallas, TX, and his virtual location is http://www.joe-milazzo.com.

William Lessard has writing that has appeared or is forthcoming in American Poetry Review, Best American Experimental Writing, FENCE, Beloit Poetry Journal, and the Southwest Review. He is Poetry & Hybrids editor at Heavy Feather Review.

[1] Marketing and public relations.

This post may contain affiliate links.