Megan Kakimoto: Take us through the construction of this collection. When did you begin these stories, and how has your vision of the collection changed (if at all) from when you first started writing until its publication?

Kim Fu: I started writing these stories in earnest in December 2017, though some of the ideas had existed as images or single lines in a notebook before that. At the beginning, saying I was working on a full-length collection seemed presumptuous, or even like a jinx. It was too daunting to think about. I just wrote one story after another, conscious that they were thematically linked but trying not to dwell on it, to focus on just getting each one right.

I would say I didn’t have a clear vision for the collection as a whole until I had drafted nearly all of the stories, when I asked a friend, who had been reading as I went, what stuck out to them, what they remembered. They remembered the literal monsters: the sea monster, the bugs, the winged girl, the hooded Sandman, the haunted doll. Reframing all of the stories, in my mind, to be about monsters—mostly metaphorical ones—helped me through structuring the manuscript and the revision process. I continue to see the book as a kind of bestiary, a monster compendium.

Recently, I was flipping through a journal from late 2019, and I saw that, at a point when I had written at least one full draft of eleven of the twelve stories in Monsters, I wrote about feeling like I should just quit, I would never finish, the book would never be published. I bring this up in the hopes that it’s a comfort to any writer feeling that way right now!

Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century is your first story collection. How did the writing process differ, if at all, from that of writing your previous two novels? Do you tend to gravitate more to the novel form or to the short story form?

Once, at an event, someone in the audience asked me if I’d ever write a biography. I can’t imagine it, but at the same time, I wouldn’t rule it out. My interests as a writer have been in constant flux over the course of my career, and I genuinely feel like I have no control over it. Short stories were all I wanted to write for a few years; as of this moment, my attention seems to be turning back towards the novel. The two forms feel completely different to me, as different from each other as from poetry, essays, reported features. The comparison I’ve often made is that writing a novel feels like trying to build a house while living on the construction site—a slow, messy, majestic process, pouring the foundation and roughing in the framing while it still isn’t keeping out the wind. Writing a short story feels like trying to put together the internal workings of a watch—setting every tiny gear and jewel in its place, seeing if it will run. The constraints, frustrations, and joys are quite distinct.

In addition to writing remarkable prose, you are also an accomplished poet. Do you see your poetry figuring into your short stories?

I think there’s a lot of learn from poetry, for fiction writers. Poetry tends to put a lot of faith in the reader, for example—poetry trusts the reader to make leaps and connections that aren’t obvious—and I think the moments where fiction demands that level of construction and engagement are often the most powerful. I also think reading and writing poetry encourages you to try to see the world in new ways, to find fresh descriptive language and new associations, to treat everything around you as worthy of close study, which is useful in every kind of writing.

Something I admire so keenly about this collection is the way your stories approach the strange and the unreal with both ferocity and fearlessness. Did you feel any pressure to give yourself permission to write into the speculative? How do you bring forth that fearlessness into every story?

Thank you, that’s so kind! In the past, I’ve had speculative ideas fall apart because I got bogged down in the mechanics, fixated on the science of how they’d work and their global repercussions to the degree that I lost sight of the smaller, human stories I wanted to tell in the first place. I still enjoy researching and thinking about this kind of thing, and I do think you have to have a clear technical understanding for yourself, off the page, but it helps me to focus on working towards emotional believability, rather than literal believability, where characters’ emotions feel earned and true, no matter how absurd or fantastical the scenario. This goes back to your question about poetry—out here, in the real world, we’re confined to what is, what can be, the physics of our universe. Isn’t it remarkable that we can read and write beyond that, to what can only be imagined? Wouldn’t it be a shame not to take advantage of that?

There’s an immediacy to your stories that I find incredibly refreshing, particularly in speculative work. Rather than flush readers with backstory, you’ve brought us right into the unrelenting present. Was this a conscious decision? And how do you see this immediacy figuring into your work?

The “unrelenting present”—I love that! Personally, when I read a short story, I want to be immersed and on board right away, in a way that I don’t necessarily demand of a novel. Short stories have less space to convey a whole world, to connect us with characters that feel fully realized. I think you have to hit the ground running, and revise down as far as you can, to where every sentence and beat feels essential. In all fiction, though, and even in memoir and essays, I personally prefer writing scenes—sensory detail and action in a specific time and place, the immersive moment—to other kinds of storytelling, though those other ways of telling a story can be equally as interesting and vital, in other hands.

This collection is so playful in regards to form. From the opening phone conversation in “Pre-Simulation Consultation XF007867” to the inventory of fantasies collected in “In This Fantasy,” the creativity here begs the question: how do you approach form in your writing? Does form ever come before story?

For this book, at least, and for those two stories in particular, form and story came hand in hand. I often play out conversations in my head between two voices, as a way of getting to know characters, or to think through opposing points of view on an issue or problem. I suspect a lot of people do this. When I started “Pre-Simulation,” I don’t think I knew it would stay entirely dialogue—I probably intended to build conventional prose around it later. But as the world and characters revealed themselves to me, the form became central to the plot, allowing for certain reveals and ironies that wouldn’t be possible otherwise. “In This Fantasy” likewise reflects something of my typical early drafting process: I often start by stacking together images in the poem-like, list-y form this story has, knowing they share characters and a voice, knowing they’re connected but not knowing how. Again, as the character at the center became clear, the one doing the fantasizing, the form became a core element—the structure told its own story alongside the smaller vignettes that comprised it.

In “#ClimbingNation,” we see the character April masquerading as a friend of the deceased climber Travis at his memorial, only to learn they hadn’t actually met before. I’m fascinated by how directly social media—and technology in general—figure into this collection, bringing forth characters who, despite their persistent use of social media, appear lonelier than ever. This is a state that feels deeply embedded in our own society today. Is this something you were hoping to explore in your fiction?

Yes, and I’m actually not sure I’m done exploring this topic, either. I had to stop using social media, years ago now, because I just wasn’t capable of having a healthy relationship with it. I respect anyone who can, but for me, it consumed all of my time and drowned out my thoughts; it made me perpetually anxious and angry, and frankly, a worse person, more concerned with the appearance of morality than the actual morality of my real life choices and behaviors. I wouldn’t have been able to write this book, or likely any book, if I’d stayed. Since the pandemic began, I’ve been comforting myself with podcasters and YouTubers who, intentionally or not, encourage you to pretend that they’re your friends in a way that I recognize is unhealthy, and no substitute for the human connections that have been lost or diminished in the last two years. I agree that these parasocial obsessions, like the one in “#ClimbingNation,” ultimately make you lonelier. I think I still have a lot I want to say about all of this! Let’s see if it makes it into my next book.

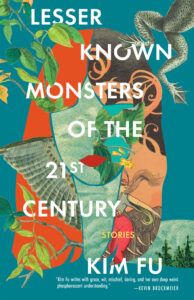

Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century

Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century

By Kim Fu

Tin House Books

February 2022

Megan Kakimoto is a short fiction writer based in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. She is currently a Fiction Fellow at the Michener Center for Writers. Her work has been featured or is forthcoming in Boulevard, Conjunctions, Joyland, and elsewhere. Follow her on Twitter @megankakimoto.

This post may contain affiliate links.