This piece was originally published in Full Stop Quarterly: Winter 2021. Subscribe at our Patreon page to get access to this and future issues, also available for purchase here. Your support makes it possible for us to publish work like this.

For a highly specific set of people—those of us in the United States, lucky enough to work from home during the pandemic, and now to receive vaccines—lockdown is waning. A quarantine is a luxury, and the vast majority of the world’s population didn’t have one. For essential workers, unhoused people, and a huge majority of people in the Global South, quarantine wasn’t an option. But while quarantine is not a universal experience, is a very distinct form of domestic life, and one that is not necessarily new. The malcontents of quarantine life—especially for women—recall other forms of domestic confinement, from self-inflicted agoraphobia to endless household drudgery.

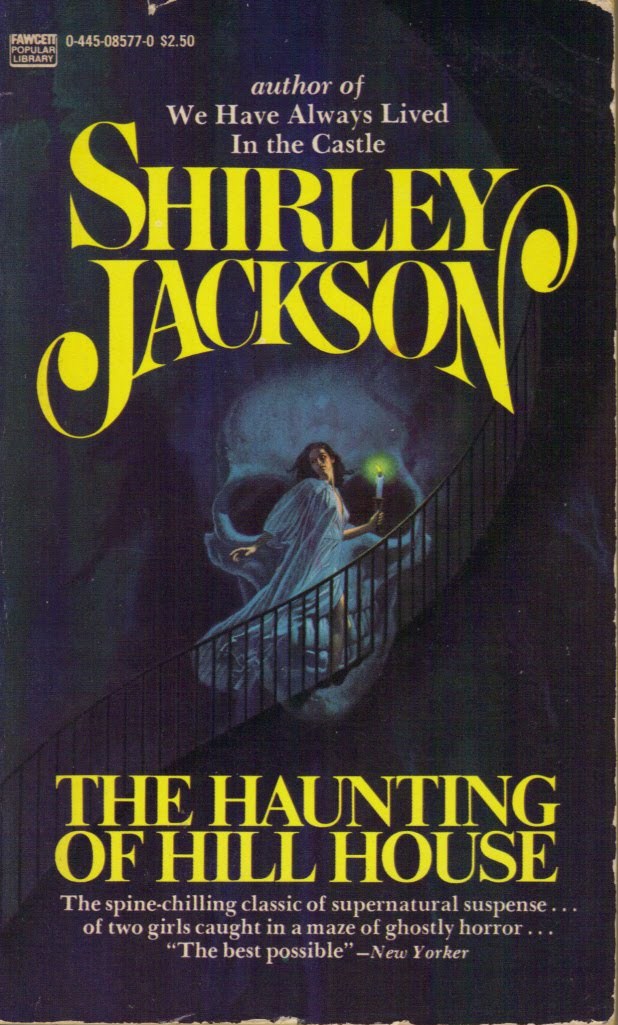

Shirley Jackson’s work, and her 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House in particular, are ideal texts for us to return to as we return to the world. Hill House, which helped to cement the haunted house genre, thematizes the psychological and even supernatural effects of indoor isolation. While this phenomenon feels particularly resonant in the midst of a quarantine that continues to wax and wane, I want to suggest that COVID-19 lockdowns, with the attendant struggles of Zoom school, endless dishes, and cabin fever, are merely the most recent entry in a long and varied history of being trapped at home. This history is distinct from more severe forms of imprisonment; in fact, it’s often demonstrably middle class. The plight of a confined white woman one of feminism’s most recognizable stories across time. Jackson’s novel, which chronicles a crisis of self after years of daughterly domestic service, suggests the warping effects of isolation for American women, beginning long before March 2020.

Jackson is well known for her blockbuster first paragraphs. Her opening to Hill House is no exception, but I think the real showstopper, which gives immediate insight into the psychological condition of her protagonist, comes a little later, on page three:

“Eleanor Vance was thirty-two years old when she came to Hill House. The only person in the world she genuinely hated, now that her mother was dead, was her sister. She disliked her brother-in-law and her five-year-old niece, and she had no friends. This was owing largely to the eleven years she had spent caring for her invalid mother, which had left her with some proficiency as a nurse and an inability to face strong sunlight without blinking. She could not remember ever being truly happy in her adult life… Without ever wanting to become reserved and shy, she had spent so long alone, with no one to love, that it was difficult for her to talk, even casually, to another person without self-consciousness and an awkward inability to find words.”

This passage sets up the character traits that will make Eleanor vulnerable to the spirits haunting Hill House, but it also gestures toward Jackson’s own agoraphobia. In her later years, she rarely left her home; biographer Ruth Franklin writes that she “found it impossible even to walk from the house to her beloved car.” Her last novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962), even more directly addresses the plight of women who can’t bear to leave the domestic sphere. Hill House was composed before Jackson’s agoraphobia set in, but already she was keenly aware of the strange contractions of self that occur when we’re welded to a domestic space. “The house is the haunting (can never be unhaunted),” Jackson wrote in her notes for the book, as well as “The house is Eleanor.”

Eleanor’s experiences are both shaped by her social constraints, especially those for middle-class women at midcentury, as well as more amorphously psychological. Staying inside for a year blurs the boundaries of the self—not irreparably, but enough to make us a little bit creepy to ourselves. The Haunting of Hill House expresses this predicament, with great spooky clarity, as a haunting. Eleanor’s social sensibilities have atrophied in a way we might find familiar.

The supernatural investigator/anthropologist Dr. Montague and homeowner Luke recruit Eleanor and Theodora to experience the infamous and abandoned Hill House because they have reputations for experience with supernatural phenomena; Eleanor was the source, it seems, of a mysterious hail of stones when she was a child. Upon her invitation, Eleanor runs away from her home and steals the car she shares with her sister to visit Hill House. Starved for interaction and affection, she can’t relate organically to her co-investigators: the doctor in charge, Montague; her sometimes-crush, Luke; and her foil, the bohemian and mysterious Theodora. The four collaborators become an ad hoc family that can only react to each fright as it appears, from the frantic banging on their bedroom doors at night to Theodora’s clothes being drenched in blood. Ultimately, Eleanor finds herself in the crosshairs of the house’s malevolent powers. An invisible hand writes “HELP ELEANOR COME HOME” on the wall, and soon after Eleanor begins to lose her grip on reality, dashing up the rickety library staircase, the site of an infamous suicide, in the middle of the night. The other investigators, frightened by her erratic behavior, insist that she leave, which horrifies her. “The house wants me to stay,” she tells Dr. Montague, and ultimately the house claims her in a sudden suicidal climax. We might read this possession as both a literal supernatural event and a metaphor for the way that domestic environments can invade and unmoor the psyche.

To begin with, Jackson demonstrates how isolation can confuse the boundaries of the self. So much of Eleanor’s internal monologue involves reorienting herself as a subject in a social world. “Eleanor thought, I am the fourth person in this room; I am one of them; I belong” (43). A few pages later she thinks, “What a complete and separate thing I am, she thought, going from my red toes to the top of my head, individually an I, possessed of attributes belonging only to me. I have red shoes, she thought—that goes with being Eleanor…” (60). Eleanor meditates on the arrival of her selfhood as it reemerges in a social sphere. Where her life with her mother rendered her identity inarticulable, in Hill House, she can recognize herself as distinct, “individually an I.”

Without the familiar restrictions of her family life, this autonomy is ultimately fragile. In the end, Eleanor surrenders her newfound independence to the intrusions of the house: “It is too much, she thought, I will relinquish my possession of this self of mine, abdicate, give over willingly what I never wanted at all; whatever it wants of me it can have” (150). Franklin suggests that Jackson’s circumstances during the writing of Hill House inflect its housebound spookiness; she was trapped in an increasingly unhappy marriage marked by her husband’s infidelity and her own wifely responsibilities. “To be married,” Franklin writes, “Shirley always feared, was to lose her sense of self, to disintegrate—precisely what happens to Eleanor in the grip of the house.” The risks of disintegration extend to women outside of marriage, too. Eleanor, a spinster in her thirties, has her identity subsumed in familial care and unpaid labor much like Jackson did. She is tormented for her childishness and her crush on Luke, feminine traits that render her more vulnerable to assault by the house and derision from her companions.

Jackson’s fascination with the horrors of confinement anticipate a feminist talking point that would dominate the second wave. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique remembers the 1950s, the decade of Hill House’s composition and publication, as a watershed moment for women trapped inside. “Many women,” Friedan writes, “no longer left their homes, except to shop, chauffeur their children, or attend a social engagement with their husbands.” The pressures of middle-class domesticity, Friedan assumes, requires women not only to give up professionalization but also to stay at home nearly all the time. This concern about incarceration within the home (which tended to outstrip concern for actually incarcerated women, largely women of color) continued in subsequent decades. In her well-known essay on compulsory heterosexuality, Adrienne Rich includes on her list of ways men oppress women: “confine them physically and prevent their movement.” Her examples run the gamut from “economic dependence of wives” to purdah and foot-binding.

Although Jackson wrote largely before the advent of this second wave movement, and rarely identified herself explicitly with the feminist movement, her own writing demonstrates similar preoccupations. She wrote a satirical essay about the personage of the “faculty wife” of the 1940s and 50s, a character she was very familiar with, being married to Bennington College professor Stanley Edgar Hyman. The faculty wife, she wrote, has “little pastimes, conducted in a respectably anonymous and furtive manner… [including] such activities as knitting, hemming dish towels, and perhaps sketching wild flowers or doing water colors of her children.” According to Franklin, the accompanying illustrations, contributed by another faculty wife, depict housewives without faces.

The Haunting of Hill House, and its story of Eleanor’s collapse, depart from the standard second wave account of the confined housewife in a few important ways. First, Eleanor is not a wife, but rather a lonely spinster with no household or husband of her own. Jackson’s own vision of feminine restriction extends beyond the marriage relationship to all women beholden by duty to care for family. Second, the consequences of this suffering take on supernatural proportions. Rather like Friedan’s description of housewife malaise, “the problem that has no name,” this unease takes on the menacing threat of an unnamed haunted power. Jackson makes clear that no singular tragic event made Hill House dangerous; it is “disturbed, perhaps. Leprous. Sick. Any of the popular euphemisms for insanity.” It may even have been “born bad.” With her refusal to assign evil more specifically, Jackson associates the domestic more broadly with totemic power. Merely being inside the house—especially if you have been made vulnerable by years of domestic confinement and service—is enough to drive you mad.

Most critics read Hill House itself as the most menacing domestic presence in the novel, as its horrors occupy the majority of the plot. But for Eleanor, the haunting began long before, in circumstances that reflect specific gendered constraints. Like a great number of Jackson’s protagonists, she is tormented by the memory of her mother. The legacy of that relationship, marked by cruelty and mutual dependence, primes Eleanor to be haunted by the house. When the group prepares to investigate the house’s creepiest room, the library, Eleanor shrinks back. “’I can’t go in there,’” she says, confused, “‘My mother—’”. She can’t finish the sentence, or maybe that’s the entire sentence itself. Her years of caretaking have warped her ability to meet new uncertainties.

Eleanor’s family life occupies a relatively small amount of the novel’s attention, although it is the catalyzing incident. This is why I want to suggest that the most illuminating adaption of Jackson’s novel is not the 2018 Netflix series The Haunting of Hill House, which retains little more than character names in order to spin a yarn about the enduring power of nuclear family. No, the best update to Jackson’s work is another novel, by Ottessa Moshfegh, a noted Jackson fan: her prize-winning novel Eileen, published in 2015.

Eileen is the story of a lonely young woman’s last days in her frigid New England hometown, and thus the last days of a miserable protracted adolescence. When a charismatic older woman is hired at the prison where Eileen works, Eileen’s desperation for a friend draws her into an ill-conceived plot for revenge that ultimately propels her from her home.

While not an explicit homage, and never identified as such, Eileen makes repeated allusions to Eleanor’s predicament at the start of Hill House, down to the similarity of their first names. Simply put, Eileen retells the story of Eleanor’s flight from her family home, before she ever reaches the next haunted house. Eileen is a historical novel, set in the early sixties. Like Eleanor, Eileen lives in a small New England town and looks after an unkind parent; she half-heartedly monitors her alcoholic father. Like Eleanor, she has lost a mother that she nursed for years; ambivalent and resentful grief pervades both women’s psyches. Like Eleanor, she has a sister with more romantic success than she has. Both women are sexually inexperienced and nurse crushes on boys while ultimately being seduced by the charms of older, winsome women—Theodora for Eleanor, and antagonist Rebecca for Eileen. While no ghosts appear to haunt Eileen, the story’s sense of unease gradually develops into horror, with the main character suddenly conscripted into an unwilling murder.

Reading Eileen helped me articulate the volatility that isolation could inspire in young women at midcentury, as demonstrated so vividly by Jackson herself. With her retrospective eye, Moshfegh agrees with Jackson that confinement for middle class women was becoming unbearable. She also echoes Jackson’s sense that isolation has its roots in grief, often ambivalent grief. This sense of unease and dissatisfaction, at least according to Friedan, gave way to the rise of second wave feminism. But these novels register the power of female isolation less as productive anger, more as destructive force.

Moshfegh registers that unbearableness without a haunting; her generic interests tend toward a painful form of hyper-realism, with thriller-style twists. Eileen Dunlop, like many of Moshfegh’s protagonists, is gross. She doesn’t wash her hands, puts off bathing, and relies on purgative laxative sprees. She eats mostly peanuts and mayonnaise on white bread. Moshfegh’s characterizations can read like a dare, pushing the reader to sympathize with a prickly and unpleasant person. Because the novel focuses on the period before Eileen leaves her confining childhood home, it articulates with grimy detail the stresses of staying home, and what isolation can do to our personal habits. Eileen’s isolation is so pronounced and her self-loathing so acute that self-neglect becomes normalized.

Moshfegh diverges from Jackson’s conflation of confinement with haunting by exploring themes of incarceration. Eileen’s father is a corrupt, drunken former cop, and the police force covers up his abuses, a dynamic that is familiar to our own context although this novel is set in the 1960s. The older Eileen, narrating her tale, says, “I will tell you frankly that to this day there is nothing I dread more than a cop knocking at my door.” Young Eileen has a job at a juvenile prison for boys, which provides additional sources of bleakness and injustice to her life. Moshfegh frames her protagonist’s isolation as commensurate with abuses of police power and other forms of imprisonment.

Eileen also makes a fitting chaser for Hill House as strange entries into the housewife literary canon, despite the fact that they are neither housewives nor mothers. Nevertheless, these texts reflect another, less often acknowledged form of confinement for women. Eleanor and Eileen are not only spinsters, but also women trapped in protracted adolescence by their restriction to the family home. Without the license to adulthood provided by marriage, they are reduced to perpetual teenagers. Eileen admits that her favorite fantasy is that her crush would “throw stones at my attic window, motorcycle steaming out in front of the house, melting the whole town to hell,” although she never speaks to him. Eleanor’s own desperation reflects her lack of autonomy in her normal life; as a 32-year-old woman, her family treats her like a child. “‘I haven’t any apartment,’” she admits to Theodora near the end of the novel. “‘I made it up. I sleep on a cot at my sister’s, in the baby’s room. I haven’t any home, no place at all. And I can’t go back to my sister’s because I stole her car.’”

The strength of these characters, created both during the midcentury moment and retrospectively, suggests the reality of confinement far beyond the well-skirted housewife stereotype. Being kept inside the nuclear family home has stripped these women of their adulthood and eventually, their selfhood too.

Ultimately, Eileen’s revision of Hill House casts a new light on what confinement means for a young woman. Like so many people, Eileen’s misfortunes have made her callous. Her desire for friendship and indifference to others’ suffering are what draws her into the climactic events that motivate her to at last flee her hometown. “Back in X-ville,” she reports, “I’d read tales of violence in the prison files—awful business. Assault, destruction, betrayal, as long as it didn’t concern me, it didn’t bother me. Those stories were like articles in National Geographic.” In fact, Eileen’s sensibilities are offended only because it becomes clear that the conniving Rebecca wants not to be her friend, but to recruit her to a violent scheme. In Moshfegh’s reimagining, domestic confinement becomes an exploitable quality, a force that muffles empathy and makes her desperate for affirmation at any cost. A similar twist comes in Hill House, when Eleanor’s possession turns her chaotic and desperate for approval, eventually resulting in a suicidal climax.

These novels reveal the degree to which loneliness makes women vulnerable and destructive, and the way that unacknowledged grief warps their engagement with the social world. Both Eleanor and Eileen have lost their mothers and been unable to fully mourn those losses. Eleanor fears that her own momentary negligence led to her mother’s death; the one time she didn’t respond to her mother’s call, her mother died shortly after. Eileen’s mother’s cruelty makes her a difficult figure to mourn. That extended grief makes them manipulatable by natural and supernatural forces of charisma. In vacuums of affection, any new force quickly reorients their priorities. Jackson and Moshfegh take different literary approaches to this phenomenon. But whether evoked through hauntings or hyper-realism, these novels represent young and pent-up white women as unpredictable and volatile, but also an untapped resource. Women of their generation and background would shortly form the center of a women’s rights movement as well as the countervailing anti-feminist movement alongside the likes of Phyllis Schlafly. As such, it’s fitting to describe them as both as objects of pity as well as subjects—however ill-defined—of growing and destabilizing power.

Though it is too soon to tell, and the pandemic only renewing its power, we may find the consequences of quarantine isolation to be similarly uncertain. It’s possible that the strangeness bred in us by more than a year of lockdown may be productively channeled toward social change. On the other hand, it may hamper us with grief and longings for which we have no words.

Ana Quiring is a PhD candidate in English at Washington University in St. Louis. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Avidly, and Feminist Modernist Studies. She tweets @AnaQuiring.

This post may contain affiliate links.