“Step across the ancient threshold and up / to the Temple of Heaven, home of Ishtar, / That no king will outdo. / Climb the wall of Uruk, walk its length.” From a modern perspective, there is something uncannily cinematic about Gilgamesh, guiding our introduction to this ancient epic like a long tracking shot. “Now look for the cedarwood box, / undo its locks of bronze, / and open the door to its secrets, / take up the tablet of lapis lazuli and read aloud: / read of all that Gilgamesh went through, / read of all his suffering.”

Like many of you, I suspect, without pressing the matter too far, there are large gaps in my reading history. It was with great pleasure that Sophus Helle’s brilliant new translation of Gilgamesh filled one such gap. As should be evident from the passage above, Helle immerses us in the materiality of ancient Babylon – within the city of Uruk, deep in the cedar forests ruled by the feared Humbaba, and beyond the edges of the known world where Uta-napishti presides over the secret to immortality. Framed by an Introductory essay that provides a “need to know” guide to the text, and five subsequent essays that explore themes within and around the text– from reception history to the obscure emotional motor driving the characters –, Helle brilliantly renders this epic in such a way that it speaks to contemporary concerns (climate change, sexuality) without losing its distinctive feel amongst other ancient epics.

I spoke to Helle about the formidable challenges of translating a text like Gilgamesh, which comes to us in fragments and is thus shadowed by absences, how it serves as a “cultural seismograph” for different generations of readers, its status as both world literature and literature belonging to a specific place, and how it keeps making uncanny appearances in modern culture.

Michael Schapira: A natural place to start is to ask where this project originated. I know you translated Gilgamesh first into Danish with your father, but you’ve also been studying the epic for a long time.

Sophus Helle: The core of the book, chronologically at least, is the chapter “The Storm of his Heart,” which is about violent emotions in the epic that are often obscure to the characters being driven by them. That was the subject of my MA thesis, and I wrote that into a chapter. I then decided it would be good to have other chapters to present Gilgamesh to a broader world-literary audience that didn’t necessarily know the epic all that well. I then pitched that to the press and they were excited about the book, but felt that an introduction to Gilgamesh couldn’t stand on its own: if this book was to have a chance, it would need a translation to go with it. I was so close to rejecting that idea outright, because I felt overwhelmed by it, and it was actually my partner who talked me into doing it. One reason I ended up agreeing to it is that I had already translated the epic into Danish, so I felt emboldened to do an English translation as well.

Why were you so hesitant? Is it just a monumental task that you weren’t up for, or are there particular aspects of translating Gilgamesh that are uniquely challenging?

There certainly are challenges, and we’ll get back to those. But I mostly felt that this is the text in the literature of the ancient Near East, and I’m still in my twenties, so it felt a little hubristic to go for it. But I never felt that there were too many Gilgamesh translations. I know that a new one is currently being prepared by Simon Armitage, the poet laureate of the UK, and I’m happy about that: the more translations the better. If you look at how many translations of the Odyssey are out there, I don’t feel like there is an excess of Gilgamesh.

My wife studies Russian literature and is also a young scholar. In her field doing a major translation often doesn’t count towards “scholarship” if you are up for tenure or something like that. Is there something similar in your field, where people are disincentivized to take on these translation tasks because, in order to advance in the field, they stick with criticism?

There is a similar dynamic in our field. It’s not so much between criticism and translations, but between text editions—very philologically based studies—and basically anything else, including translation but also criticism. If I’d written a book including only literary criticism of Gilgamesh,that might not have counted towards an Assyriology position either. It is a very philologically dominated field, with an understanding of philology that is still centered around text editions. I’m not necessarily criticizing that focus—it’s just the way it is.

But being an academic is not my dream job anyway. My dream job is to be a popularizer, writing about ancient literature for broader audiences. Now, that might require getting an academic position to sustain me, but bringing Gilgamesh to a larger audience was more important to me than securing a position.

Nevertheless, you are interested these scholarly fields, and you shared an article with me that will be published later this year about philology — its history and its current confused moment. For outsiders, could you share a little about what going on in philology and what got you interested in thinking about its current state?

Philology is, as you say, at a very interesting juncture. I haven’t really found a good to for describe the wave we’re seeing now. I’m now a big fan of “turns” and “neo-‘s”, but I do see a change going on. I suppose that one way to describe it is as a “world philology,” but others would contest that.

One aspect of this change is a re-orientation towards philology as a whole. For much of the twentieth century, philology was fragmented into a number of subdisciplines, and so scholars wouldn’t not see themselves as philologists first and foremost. Perhaps if you were a classicist, you might call yourself a philologist, but most scholars would say that they were Egyptologists, Assyriologists, Indologists, Japanologists, Sinologists, and so on. Now, we’re seeing an emergent sense of philology as what I call an “anti-disciplinary discipline,” meaning that it is both a space for communication across these subfields and a coherent practice in itself.

This more globally oriented form of philology is accompanied by a series of critical self-reflections on the history of the field, which is not always a particularly pleasant history. Further, there is a growing awareness that philology is not just a modern phenomenon. If you look at discussions of “What is philology?,” it used to be almost exclusively anchored in post-Lachmannian philology, meaning European philology from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Now, there is a much richer sense of philology as something that was done in Babylon, in ancient Alexandria, in medieval China, in early modern India, and so on.

I was thinking about this in conjunction with a book that came out a few years ago, Philosophy Before the Greeks by Marc van de Mieroop, which discusses whether there was something like philosophy as we understand it today in ncient Babylonia. The answer is really complicated, and you go back and forth on this issue, but there was no question that there was something very much like what we call philology. It is immediately apparent. What they were doing is surprisingly similar to what we do today under the banner of philology.

And I really like that: I like this sense of philology as global both in the sense that we can study all sorts of cultures using philological practices, and in the sense that all sorts of cultures were doing it practicing it.

That seems to square nicely with your desire to not just be an academic — to take philology out of its institutional casing.

We can move into the text in a moment, but I have one more question outside of the text. In the essays surrounding the translation you talk about the reception history and Gilgamesh being a “cultural seismograph.” When you first encountered the text, what were the kinds of framing preoccupations that you brought to it? I was just teaching “Genesis” last semester so when you get to the flood story in Gilgamesh your mind immediately jumps to that. What major resonances are there when you read the text?

Before I answer that question, I want to say that what you are pointing to is an essential feature of how I’ve come to understand the epic, and an essential feature of why the epic continues to work as a literary text. I’m doing a number of interviews and lectures about Gilgamesh right now, and the theme that keeps popping up is how many things you can pick out of this text. It’s like a more complex version of a Rorschach test, a literary kaleidoscope that you can turn many ways and see so many patterns within. What you pick out often says a lot about you.

I first read Gilgamesh when I was choosing whether to study Assyriology or Egyptology. Ancient Egypt is a wonderful culture, and there are so many interesting things to say about it. But it is also a culture that loves stability, symmetry, peace, and whose ideal afterlife is one where everything is harmonious. In Babylonian texts, by contrast, you see a fascination with paradox and endless amounts of unresolved angst. That was part of what attracted me to Gilgamesh, which led me to write that core chapter of the book I mentioned earlier, about the emotions that are both intense and obscure. And that’s definitely because I relate to that aspect of the epic.

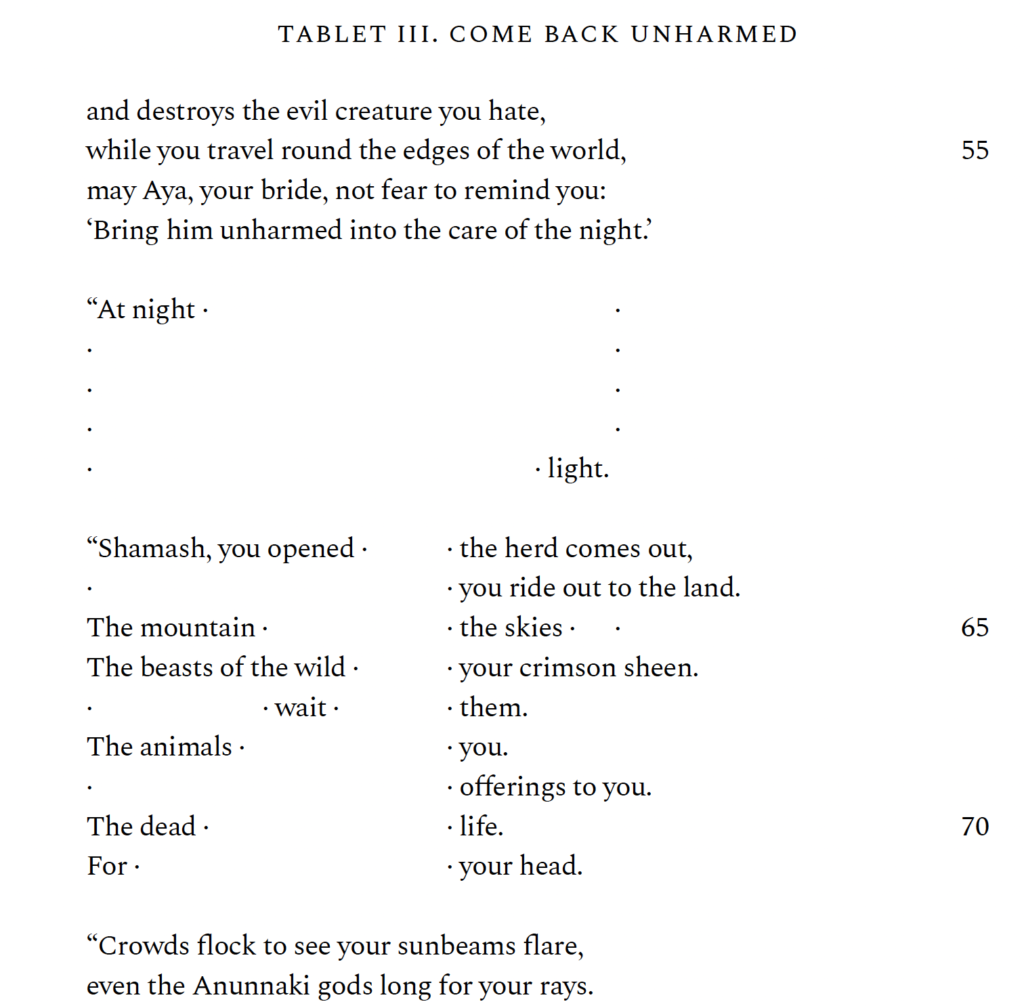

There are so many, as you were saying, particular features to this text, as compared to the Odyssey or other ancient epics, but one of the big ones are these missing parts that you include graphically in an interesting way. I found myself appreciating those absences and having them contribute to the story in ways that I wasn’t expecting. Did you have a similar reaction when you were first getting acquainted with the text? Have you thought about these absences as being integral to the text, and paradoxically would it lose something if we were to find some extant clay tables that filled in these gaps?

It’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot these days, because I’m discussing it in my next project, which will be about “the poetry of crises,” as I’m calling it. It will be about the way philological crises such as absences or manuscript variations can contribute to our understanding of the text and our aesthetic appreciation of it, even as they take something away. One of my core example is exactly the passage you highlighted in your question: the death of Enkidu. It’s such a strong passage, and it has so many resonances with the Black Page in Tristram Shandy. The absence of text as Enkidu dies is very powerful to me, and you’re right, it would be weird to me if and when—because it is likely to happen—a manuscript is found that fills out this blank space. Maybe it will be great, maybe not. Who knows?

When my father and I were working on the Danish translation of Gilgamesh, a new fragment appeared that made us reconfigure parts of Tablet II. After I finished that translation, and while was working on the English one, a new fragment appeared yet again, and I’m sure another will be found by the time the next translation comes out. That points to the instability of the text, which in itself is really interesting. It’s not just the absences that are compelling, but the way the text changes, which makes it feel oddly alive—even though, if anything, it shows how dead it is.

The depiction of fragments is an interesting story. When I was making the Danish translation with my father, we had two teams of graphic designers working on it at once—one that we hired through the press and one that my father knew: Wrong Studio and Åse Eg. We pitched this question to them, about the depiction of the absent text, and they would send in proposals, which I would then test with my students. At one point, I was really set on it looking like a redacted document with these thick black lines crossing out the absent text, but everybody else hated that idea. In the end, it was literally a conversation with a team of designers on each phone, and we ended up going with the raised dot.

To get into the translation itself, I sent a question to you about one particular phrase that I found so interesting and poetic. As you explain in one of the essays, this is just when people are about to engage in direct speech. But they use this phrase “he worked his words.” It led me to think about how differently things would have felt in this culture. Were there any phrases or metaphors that helped unlock the feel of this culture, like how people related to things like direct communication that would strike us as strange?

With “work his words,” the thing to note is that the phrase is very common, and all translators of Akkadian poetry must come up with a solution to it. The problem with the phrase is that both words are so neutral. Pāšu literally means “his mouth,” and īpuš means “he (or she) did,” but both words can mean a thousand different things depending on the context. When you put them together, you can tell that it refers to speech in some way, but the question is how is. For me, the important aspect of it is that Akkadian poetry in general, and Gilgamesh in particular, has this amazing aural quality—not oral in the sense that it was performed, but aural in the sense that it sounds compelling to our mental ears. It is so full of alliteration and verbal games, and this phrase is no exception. Pāšu īpuš sounds amazing, especially if you elide the vowel ending, as first-millennium scribes probably did: pāš–īpuš. There is too little scholarship on Akkadian alliteration, rhythm, and verbal games, but once you start looking in Gilgamesh,they are everywhere. There is a wordplay, if not every other line, then in every fourth line. That’s something I wanted to convey in my translation, and “work his words” is an example of that.

As for what metaphors were used to describe speech and text production, the one that is particularly interesting—not because it’s so different from us but because it is so similar—is the textile metaphor. That’s something I’ve written about elsewhere, in connection with metaphors of authorship. The image of text as textile is the leading global image for how words are put together: words and threads are juxtaposed in culture after culture. You also find that connection expressed in Babylonian and Sumerian culture in a variety of ways. For example, an author is called a “weaver (or binder) of words.” You see a few of those textile images in Gilgamesh, but Gilgamesh is generally more focused on the materiality of texts, so it prefers images of clay, of the lapis lazuli that the epic is supposedly written on, and resonances with other sorts of materials, such as Enkidu’s statue. In Gilgamesh,the focus on textuality is often about the stuff of which it is made. Right from the start, the text lists the materials that surround it: the cedarwood box, the locks of bronze, the tablet of lapis lazuli. It’s all stuff.

It’s also so architectural. The beginning asks you to walk along the edges of the walls of Uruk. You feel the dimensions of the world.

Another thing that you mentioned earlier that I found interesting is that for a relatively short text, at least compared to other epics, there are tons of characters. Are there any minor characters that you find yourself thinking about? I thought a lot about Humbaba, the guardian of the cedar forest. I felt really bad for him. The gods put him there for a reason, and in our age of environmental devastation he made a reasonable case as to why he should be spared. What about you?

A bunch of my friends in Assyriology have side characters that they would stand up for. Shamhat is a popular candidate. My advisor Nicole Feldt is really into Shamhat, as is another Danish Assyriologist called Laura Feldt. They form something of a Shamhat club, and I get that: she’s super cool. One of my good friends, Omar N’Shea is really into Enkidu. You can get very into Enkidu as a character. There is a new book that I really recommend, Ea’s Duplicity by Matthew Worthington, and it makes a case for Uta-napishti being a much stranger character than we previously thought. The moment you start asking any questions about him, his story falls apart, which I agree is really interesting. Worthington also argues that Uta-napishti is crueler than we thought, which wasn’t my original impression, but he does make a persuasive case.

I really like Ninsun. I think she is very compelling, but that’s a view I came to relatively late. My analysis of Ninsun in the book—of her prayer gradually morphing into an order—is something I discovered just a few days before sending in the final manuscript for the book, and had to write up in haste. So if the book started with obscure emotions, it ended with Ninsun’s elegant use of language.

Your supplemental essays are really great and illuminating. Before this I’d never read Gilgamesh, so the context helped a lot. One thing that really struck me was that it wasn’t translated into Arabic until the 1960s. It is seen as this possession of world literature, but it is only quite recently that it has also been seen as literature that was locally produced in a place. It has a particular resonance there, like we talk about Egypt or Greece. I don’t have a fully formed question here, but just thought that was a really interesting dynamic. Is there more you could say about what this has done to reshape the field, or whether it has produced interesting work that we should know about?

I think that the field is only recently—and still with baby steps—growing aware of its debt to Iraq and its need to engage with Iraq as a nation. To an extent, I get why. If you were an Assyriologist in the Eighties, engaging with Iraq meant engaging with Saddam Hussein, and that was difficult in many different ways. If you had asked many Assyriologists not too long ago, “What does the Babylonian cultural heritage mean for Iraq?”, they would dismiss it and say that Saddam Hussein had made propagandistic use of it. I don’t think that’s true anymore, especially now that Saddam Hussein is becoming an increasingly distant memory. The Iraqis have a different set of concerns now, and they have many more positive associations with antiquity and the prospect of having tourisms returning to Iraq. We’ve heard a lot about ISIS in the West, but there was a subsequent crisis in the nationhood in Iraq as Southern Kurdistan tried to secede, so the issue of Iraqi nationhood remains a contested question. The cuneiform cultural heritage is a way of grounding the modern nation state in secular space, one that isn’t tied to the existing sectarian divisions. Without trying to take up a position on Iraqi politics—which is beyond me for any number of reasons—I’m just observing that the political valence of the ancient heritage has shifted a lot.

I sent you a couple questions from a Translation Questionnaire that we did several years back. There is a question about what it means for a translation to be faithful. You spoke before about appreciating the sound of Akkadian poetry. Would that be your standard for faithfulness?

[NOTE – Here are the two questions in full:

1) There’s that famous Italian expression, “Traduttore, traditore” (a play on the words for “translator” and “traitor”). And the poet and translator Rosmarie Waldrop writes, “Translating is not pouring wine from one bottle into another. Substance and form cannot be separated easily . . . Translation is more like wrenching a soul from its body and luring it into a different one. It means killing.” Why is it that the concept of translation can inspire such violent comparisons? To what extent does your own translation work feel like an act of destruction?

2) The word “faithful” often comes up in discussions of translation. To whom or what is a translation faithful? Is a faithful translation good? Is a good translation faithful?]

This is going to be an attempt at an answer—let’s see how it goes. You sent two questions. One was about faithfulness, and the other was about the wrenching of the self and the body of the text. I find myself being skeptical of that kind of statement about translation. It ultimately comes down—I think—to whether you believe that the text is an organic unity or a composite entity. Is a text something that has many aspects which are independently reproducible or re-creatable, or is it something whose various parts are so intermeshed that you cannot have any aspect of the text without having all the others? I see the text as a composite entity. I see it as a place where all sorts of things, all sorts of voices, all sorts of cultural scripts, all sorts of historical circumstances, all sorts of intentions, all sorts of readerly projections, and so on and so forth, come together. So, I am perfectly comfortable with the idea of taking a text apart. It doesn’t bother me. If you are of the school that claims that translation is impossible, or that translation is violence, then first of all you have a problem with hyperbole. I always cringe a little with these metaphors of violence, because we have enough real violence that we need to worry about in our culture. The metaphor can end up cheapening the force of vehicle.

There are so many aspects of a text that are subject to change. You can change the font of a text. You can change the materiality of a text. In short, a text is always changing; a text is a series of change. A text written in Comic Sans is not the same as a text written on vellum. Cuneiform is such a wonderful script, and you lose all the cuneiform games (signs meaning more than one thing) not just in a translation into English, but even in a transcription into Akkadian that is written with Latin letters. But that’s okay. That is how all pre-modern texts operate. Gilgamesh isn’t one entity. It is made up of two hundred tablets that are all fragmentary and that all spell the words of the text slightly differently: the poem is not written the same way in one manuscript as it is in the other. My take-away from all this is that texts are containers of difference, containers of multiplicity. Can a translation recreate all that multiplicity? Of course not. But that’s the point of a translation; it’s a picking apart of the text. Translation relies on the text’s internal differences to work.

But you also asked specifically about what faithfulness would mean in the case Gilgamesh. It was really interesting to do these two different translations of the same text, into two different languages. I was reading an essay by Theo Hermans, a noted scholar of translation, in a book called The Conference of the Tongues. Hermans is making the point that all translations of a work that has been translated multiple times into one language display an inter-translational dialogue. If you are pointedly choosing one word where the previous translator chose another, you are setting up a dialogue not just with the source text, but across translations. I could feel that happening as I was translating Gilgamesh first into Danish and then into English. These translations were of course shaped by the source text, and what the respective languages did and did not allow, but they were also shaped by the existing translations.

The existing translation into Danish was quite forceful—and I’m not saying that in a negative way. It was high-powered and great. But to counterbalance that, ours went in the opposite direction. It was rather pared down. All excess was removed. It was quite “clean,” in a sense. But I that’s not what I wanted to with the English translation. There, I was reacting to translations that were doing something different. Both Andrew George and Benjamin Foster have sought to recreate the archaic quality of the original. Already back in Babylonia, Gilgamesh was meant to sound old, as if it came from the long-gone age in which Gilgamesh was king. It would have had a somewhat Shakespearian quality to a Babylonian audience, and if you read Foster’s translation, you’ll get that sense. I therefore decide not to translate the text as archaic, but to play up the aural games I was talking about earlier, to counterbalance what was already there. Those are two different ways of being faithful to the linguistic aspect of the same text, again showing that the text is a container of multiplicity.

I have two more questions. This book The Dawn of Everything was published in the fall and was way up on the New York Times bestseller list. There has been a lot of discussion of the merits of some of the scholarship, but one thing that David Wengrow has been saying is that what motivated the book was an attempt to address this feeling of being stuck, for example of constantly thinking about inequality. Going way way back was their way of trying to get us unstuck, and David Graber had already done that in Debt (which talks a little about Gilgamesh and the origins of writing being related to accounting, which you discuss a bit as well). Because you’ve been working with these ancient texts, and because you are young and don’t want to be stuck and want the future to be different, are there things in Gilgamesh that you think are particularly helpful for getting us unstuck?

I haven’t read the book, so I can’t comment on its specific claims, but based on the reviews I’ve read, I’m immensely sympathetic to the core argument of the book. It resonates with me because my guiding motto as a historian is that “history makes the present strange.” By that I mean that the conventions we often take for granted—anything from gender roles to nation states through the way we dress or eat to our understanding of literature—lose all solidity under the historian’s gaze. The norms by which we live most often turn out to be the products of long-gone circumstances and coincidences. (I’m quoting from my PhD thesis here).

What I like about the Dawn of Everything—again, based only on first impressions—is that it shares that basic outlook. The book is written in opposition to grand historical narratives that have been rolled out time again, from Hobbes and Rosseau through Nietzsche and up to Harari, all of which use history to make the present natural, depicting the logical conclusion of an inescapable sequence of cause and effect. What Graeber and Wengrow do is to restore the sense of strangeness, coincidence, and contingency to history, which make the structures that shape our lives—not perhaps all that much easier to change, as they claim—but at least baffling, and more clearly recognizable as artefacts that could have been shaped differently.

I do often feel that the further you go back into history, the less vulnerable the texts and artefacts become to these very strong narratives. I was also thinking about Eve Sedgewick’s wonderful advice to keep your theories weak, because if you have a strong theory, it can dominate everything and fold it all back into itself. There really is something to be said for weak theory that sees patterns, makes connections, interprets things, and helps you along, but doesn’t domineer. That’s how I understand their book – setting out a purposefully weak theory for the long course of human history.

I’ve taken this weak theory approach to Gilgamesh. I don’t want this to be read as a statement about what humanity is necessarily like, for example when it comes to climate change. People often turn to Gilgamesh because it is so old and must say something enduring about humanity. But it doesn’t. It says something about one particular culture’s notion of humanity, and not even that: there are very different accounts of what human beings are like in other Babylonian culture texts. Allowing Gilgamesh its own contingency is important for getting it right.

That’s a great place to end, but I’m tempted to ask one more prurient question. What is your favorite reference to or adaptation of Gilgamesh in popular culture? You go through a whole kind of reception history that goes from popular culture to the use of language in military operations. What is your favorite uncanny appearance of Gilgamesh in the culture?

The military use you mention is a geolocation software used on drones—who knows whether it is still being used now. It’s the NSA, so our information is limited. The Gilgamesh software is a horrible piece of technology that acts a fake cell phone tower on the drone. The victim’s phone tries to connect to the drone, and the Gilgamesh software then guides the drone to its victim. I’m not sure what that has to do with Gilgamesh.

I think that the weirdest one is Project Gilgamesh, which is a collective term for bioengineering projects that aim to radically extend the human lifespan. That’s really weird. I don’t know what to do with that mentally. I’d love to do a project talking to some of these bioengineers and understand what they are up to. I sort of get why it’s named after Gilgamesh, who of course tries to achieve immortality, but did they not read to the end of the epic?

But I haven’t seen Eternals yet, so maybe that will be my favorite. I had a ticket to go and see it, but on that very day, I caught Covid.

Michael Schapira is an Interviews Editor at Full Stop.

This post may contain affiliate links.