[Scribe Books; 2021]

Tr. from the Spanish by Samuel Rutter

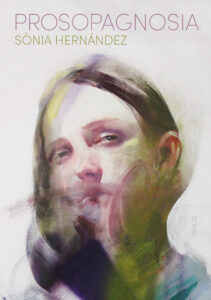

In Prosopagnosia, a 2017 novella set in the early twenty-first century by 2010 Granta Best Young Spanish Novelist Sònia Hernández, out now in an English translation by Samuel Rutter (the original title is El hombre que se creía Vicente Rojo), the teenager Berta plays a game she calls prosopagnosia, after a cognitive disorder that impairs the brain’s ability to recognize faces. She holds her breath and stares at something, like her own image in a mirror, until it becomes dissociated from memory and suggests something new. Berta’s mother is a onetime journalist in her mid-forties who writes advertising copy for an insurance firm. She fixes her attention on an old man claiming to be the painter Vicente Rojo after he applies for a job at the local high school and gives Berta one of his paintings, in front of which she has fainted while playing prosopagnosia. Attempting to restart her writing career, Berta’s mother pitches a feature on the artist to her former editor. This essay requires her to conduct a series of interviews with the impostor, by the end of which she has caught on to the deception.

At the turning point of the story, Berta’s mother experiences a kind of satori and figures out that she can choose how she sees the old man: “I could view that man as a fraud who had tried to pass himself off as an important artist, seeking who knows what benefit,” she says, “or I could see him as an individual who had been brave enough to take his search for meaning to such an extreme that when I met him, he believed he was someone else.” She applies this insight to her own situation: “I could see myself as an obese woman who had been abandoned by her husband, who is overwhelmed by her daughter’s sadness, and who hides away because everything frightens her,” she continues, “or I could see myself as a woman smart enough to make the most of her desire to discover new narratives that make the world bigger, and who works towards finding her own little corner where she can feel comfortable and where things aren’t so terrible.” The character recognizes the value of her sudden hard-won understanding and resolves to hold the ground she has gained: “Once you stumble across your desired image, you have to defend your narrative at all costs.” The change that Berta’s mother undergoes is an inward one. As a result of her decision, she will become an artist herself in the closing pages of Prosopagnosia, when she defends her narrative, as she would phrase it, by turning the story she’s writing into a work of fiction instead of reportage. She doesn’t grasp the meaning of her act of creation: she still submits the piece to the editor of a newspaper, where such a story doesn’t fit. Thus, the change in her identity from journalist to fiction writer hasn’t sunk in far enough to alter her sense of who she is in the world. Rutter’s English word choices here — “stumble,” “desired,” and “defend” — capture the confusion and excitement of the moment.

Prosopagnosia is a metaphysical novella, a fictional vision of a permanent problem in human experience, rather than a dramatization of social tensions. Hernández situates her fable of identity in the context of a globalized world. Pretending to be Vicente Rojo, the old man places the women, insecure about the working-class Catalan city where they live, in contact with the storied freedom of Mexico, the aftermath of the Spanish conquest of the New World, and the haut monde of celebrity artists and prestige artworks. The false Vicente Rojo’s presumptive father, a Republican and Communist, fled Spain to France after the Civil War and relocated his family to Mexico as political asylees at the end of World War Two. More importantly, the false Rojo connects Berta and her mother to each other, and to their world, with a symbol, diminished but alive, of the legacy of Catalan resistance to the hegemonic rule of Spanish power centered in Madrid, particularly to the Francoist dictatorship. The false Vicente Rojo claims to have returned to Cataluña, an exile come home again. His rearrival holds out a promise to the women that enlarges their identities, or their sense of themselves, even as he lies to them and, albeit briefly, tricks them about who he is. Generations of sacrifice, forbearance, and disappointment surge beneath the surface of their credulity. When the journalist at last writes her piece, the newspaper doesn’t respond, but her daughter reads the story, an invented tale about a fake Vicente Rojo — a work of fiction, in other words. Berta says she doesn’t understand, but thinks it’s “beautiful.”

Writing a short story rather than a news item, Berta’s mother does something other than what she set out to do, something she doesn’t understand or realize she has done. For her, the piece remains “the article,” but its status as a story changes because now she hasn’t reported but imagined it. “I described how the initial discomfort of the painter at having to perform publicly became a kind of cryptic complicity with the teenagers,” she writes, “who never stopped asking him about when he painted, how he decided on forms, if he preferred Catalan or Mexican food, if it really was as dangerous to live in Mexico as they said on the news, about why he didn’t have a Mexican accent when he spoke, about why he liked Mexico better than Spain, if he had been friends with Frida Kahlo, and if he would help them paint a mural with a portrait of one of their classmates who was very sick.” If the result is beautiful, as Berta says, it is also, according to the Romantic formula, untrue. Moreover, Berta’s mother’s act of artistic creation is political, in its assertion of a transpacific freedom, a moment of imaginary contact among members of the Catalan diaspora; it’s theoretical, in its implications about the emotions, thoughts, and experiences that go into an artwork; and it’s philosophical, in its presentation of incremental changes of identity and self-image.

Berta’s personality mutates by dint of her adolescence. She displays a not unpleasant combination of gravitas, spaciness, gloom, and defiance throughout the novella: “That glint of irony and disdain flickered in her eyes again,” her mother notices. Berta neglects to inform her mother that the school administration, after a spell of excitement, has discovered the false Vicente Rojo’s ruse and rejected his application because she’s too focused on convincing her mother to let her have an ibis for a pet. When Mario, a friend with whom she plays prosopagnosia, becomes terminally ill, Berta abandons this plan and instead urges her mother to convince “that artist friend of yours” to paint a mural in his honor together with the students: “They’re waiting for the final act and then they want to do something more formal, but we want to paint the mural now, so Mario can see it.” Thus, in the shadow of death, Berta’s purview broadens to comprehend the public good and the interdependence of persons.

Hernández shows how highly she regards the real Vicente Rojo in a notice written for the news site La Vanguardia last year on the occasion of his death: “In the fascinating and overwhelming Mexico City, on the afternoon of March 17 (the early morning of the 18th in Barcelona), the graphic designer, painter, sculptor and editor Vicente Rojo passed away. Among the many wonders he created is his birth in Mexico at age seventeen — a birth that was not the result of being born, but of being dazed by his discovery of the light of Mexico, and of the freedom there to live the way he chose.” It’s a statement of respect, from one artist to another, that testifies to the depth of this writer’s connection with her theme. It’s a gloss on her book too. Hernández’s way of framing Rojo’s obit — the metaphor of birth, the emphasis on liberty and self-determination, the imagery of light and shade — suggests that it’s possible for people to make their environment propitious for creativity. It also turns Vicente Rojo into the symbol he is for the community depicted in Prosopagnosia: a figure powerful enough to impel them to exceed themselves in whatever ways they can.

Erik Noonan is from Los Angeles. He is the author of the poetry collections Stances and Haiku d’Etat. His writing appears in the anthology Cross Strokes and he is an Assistant Editor at Asymptote. He lives in Oakland. For more, please visit eriknoonan.net.

This post may contain affiliate links.