[The Operating System; 2021]

Tr. from the German by Mathilda Cullen

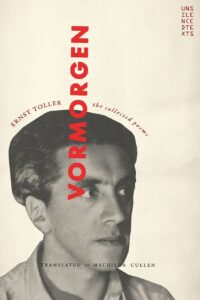

Mathilda Cullen’s translation of Ernst Toller’s poetry, Vormorgen: The Collected Poems, is a labor of love, recovering the all-but-forgotten literary legacy of an enigmatic figure. A charismatic gadfly who led international lecture tours, Ernst Toller packed many identities into a hectic life: soldier, dramatist, poet, anarchist, political prisoner, failed Hollywood scriptwriter. While he was on trial for his role in the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic — of which he was president for six days in April 1919 — prominent German intellectuals Max Weber and Thomas Mann spoke in his defense. The sympathy and loyalty he inspired in a generation of leftist thinkers is illustrated in W.H. Auden’s elegy “In Memory of Ernst Toller,” which Cullen has included in this volume. Following Toller’s suicide in 1939, Auden wrote, “Dear Ernst, lie shadowless at last among/The other warhorses who existed till they’d done/Something that was an example to the young.” Yet his notoriety also garnered skepticism and hostility, among both fellow revolutionaries who considered him an egomaniac and Nazi officials threatened by his politics and popularity. It is hard to believe that such a divisive persona could be neglected, but Toller has followed many of his German Expressionist peers into near-total obscurity. During his lifetime, he was best known for plays that couched his wartime and revolutionary experiences in heavy symbolism and incantatory dialogue, including Die Wandlung [Transformation] (1919) and Masse Mensch [Masses and Man] (1920). However, his fame as a playwright was rapidly eclipsed in the postwar period by his career-savvy Marxist contemporary, Bertolt Brecht.

His tumultuous life and works raise the question: What aspect of his repertoire does Vormorgen revive, and why does it matter now? Those who consider Toller’s life at all often characterize it as one of increasing disillusionment, as he lost both his hope for revolution in 1919 and his German-speaking audience when forced into exile in 1933. But the poems in Vormorgen capture him during the most productive period of his career, a five-year prison stint following the failed uprising. Their publication is a momentous occasion, and not just for those of us who have tracked down out-of-print editions of Toller’s work in far-flung academic libraries. As prison literature, their emphasis on execution, death, and injustice resonate with our own era, when the politics of incarceration have been top of mind. As an emblem of bygone political chaos, they still have significance. An anarchist with pacifist tendencies, Toller expressed reluctance about the power grabs of his martial-minded Marxist comrades. Further clues about the enduring relevance of Toller’s work lie in two seemingly unrelated aspects of these poems: their defiant tone and invocation of nature imagery.

Vormorgen reveals an author on an intriguing precipice between hope and frustration. Following the brutal suppression of the Bavarian uprising by the German army and right-wing paramilitaries — many of whom would later join the Nazi Party — Toller’s poetic voice registers this loss through calls for further action and elegies to fallen comrades. “An die Dichter [To the Poets]” scorns leftist intellectuals immersed in thought rather than deed: “I denounce you, poets/Wrapped up in words, words, words/You nod with your aged heads/Eyeing the vortex, smiling, sublime/Cowards buried in the trash.” The poems in “Gedichte der Gefangenen [Poems of the Imprisoned]” echo this sense of urgency. “Unser Weg [Our Way]” depicts how a revolutionary sacrament has supplanted religion, announcing, “We want to bring the kingdom of peace to the earth/To bring freedom to the oppressed of all countries/We must struggle for the sacrament of the earth!” Religious cadences remained central to Toller’s aesthetic — down to plays structured around Stationen, much like the Stations of the Cross — but these aspects of the text depict a poet ever aware of a growing audience beyond the walls of his prison cell.

But the moments of defiance conceal as much as they reveal. From a writer too easily characterized on an asymptote toward disillusionment and despair, anger and immediacy feel refreshing. Lurking beneath such glimpses of bravado, however, are shakier existential dilemmas about bloodshed, death, and politics. When combined with grimmer poems about trench warfare and prison life, these instances of revolutionary fervor compel the reader to confront uncomfortable questions. How can we comprehend violent death? How is it rationalized, valorized, or forgotten? “Requiem den Gemordeten Bruedern [Requiem to Our Fallen Brothers],” a poem with multiple speakers that illustrates Toller’s dramatic sensibility, explores this issue. In it a woman’s voice proclaims how “a mother mourns the son she’s lost/That he may be manure for an acre of new earth.” But visceral reality often intrudes on these pat narratives of blood sacrifice. Elsewhere in the same collection, recollections of the First World War dead are decidedly less elevated. “A dung-heap of rotting human bodies/Glazed eyes, blood clots/Split brains, spewed entrails/The stench of corpses pollutes the air/A single gruesome shriek.” For Toller, no ideology can entirely account for the suffering of others, even his own.

The anger that emerges in this collection may well be a product of this conflict, an aspiring pacifist caught between more violent tendencies of leftist compatriots and the mobilization of right-wing forces during the early Weimar era. Long periods of solitary confinement in a world of prisoners “who hate themselves because they are so miserably alone” no doubt heightened his sense of injustice. Cullen’s translation expresses this element of Toller’s writing. For instance, the woman’s voice in “Requiem” declares, “Wehe und Fluch dem Krieg/Wehe dem Hass!” While a more literal translation would be “Woe and curse the war/Woe to hatred,” here the lines become, “Fuck the war/Fuck this hatred.” This unmuted outrage provides insight into why Toller had an afterlife in the confrontational “in yer face” theatre popular in Britain during the 1990s, a style exemplified by the film Trainspotting (1996). Mark Ravenhill based his 1999 play Some Explicit Polaroids — depicting a disoriented former activist who contends with a consumerist hellscape after his prison release — on Toller’s Hoppla, Wir Leben [Hoppla, We’re Alive] (1926). With the chaotic political factions of his era long gone, Toller’s contempt for brutality and complacency still have resonance.

Considering the heavier aspects of this collection, it would be easy to view its incorporation of nature imagery with suspicion. Are the birds of Das Schwalbenbuch [The Book of Swallows] a diversion from traumatic memories and prison life? After all, the swallows “know nothing of justice and nothing/Of injustice.” Yet the undeniably endearing verses about nest building and eggs serve another purpose, acting as an emblem of hope and life rather than social decay. Their rituals of everyday life stand in contrast to the “jazz dances, shrill from loathsome time” and “the soul [illuminated]/With lanterns of electric greed” — an indictment of Weimar decadence. Describing the swallows’ flight constitutes “nam[ing] the unnameable” or “imagin[ing] the unimaginable,” a world beyond human political visions or power struggles. Their lives gesture toward the unnamable, a cautionary tale against human arrogance and verbose poetry alike. “Do not carry/A longing/For people/Into desire’s eclipse/Fear the word that strangles.” As pedestrian as they may seem, the elegant simplicity of these verses are a notable change of pace from the abstract imagery of Toller’s plays from the same period, which skews heavily on the side of religious martyrdom and Greek tragedy. But the ways of nature offer little respite from the poems’ troubled depictions of murder and war. Observing the birds eat a sausage and other meals, the conclusion is inescapable. “What lives, murders . . . It’s a curse of the earth/Nowhere/In divine innocence/Breathe the living/Even the dead/Must kill.” Still, watching the swallows navigate the vagaries of life — from predators to deadly frost — serves as a meaningful counterpoint to the collection’s dual emphasis on the cruel monotonies of prison and the horrors of war. It also provides a pleasant departure from the less palatable aspects of Toller’s repertoire, particularly his fixation with earth-mother or (alternately) hypersexualized feminine symbolism. When the birds have left, the poem concludes with gratitude: “In humble thanks/I think of the gift of your love.” In “unspeakable/animality,” their perpetual cycles of life and death offer a glimpse into the significance of human history. The human “struggle will only count if it births/A new struggle/And even their most sacred transformation/Will birth only further change.” In retrospect, this note of wary optimism feels especially poignant from a man who met his tragic end in exile, with most of his comrades and family interned in concentration camps. After the anger and the ravages of twentieth-century warfare, hope was here, too. Though it might benefit from a biographical or historical note for readers less immersed in German history and literature, Vormorgen is a revelation.

Emily Hershman received a Ph.D. in English at the University of Notre Dame. Her writing has appeared in the James Joyce Quarterly and elsewhere.

This post may contain affiliate links.