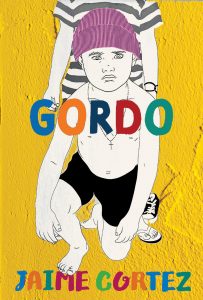

[Grove; 2021]

Watching Jaime Cortez read aloud an excerpt from his debut short-story collection Gordo, published by Grove Atlantic Press earlier this year, is a pleasure. The immediate shift in the author’s presence, from the tone of his voice to his expressions and gestures, indicates a complete immersion in the titular character — an elementary school-aged Mexican American boy growing up in a migrant worker camp in San Juan Bautista during the 1970s. However, to see Cortez act out Gordo with such care should not be a surprise, as this is just a reflection of the most impressive aspect of the eleven short narratives that make up the book: his ability to tell the stories through the voice of a child.

Although Gordo may be Cortez’s debut in its specific genre, the author has extensive experience in the literary field. Besides having his work included in several anthologies, amongst them Freeman’s Journal and Tales from La Vida: A LatinX Comix Anthology, Cortez has also published Sexile/Sexilo, a bilingual graphic novel that tells the story of Adela Vazquez, a Cuban transgender activist and performer. The topics of gender identity and sexual orientation are common in the author’s writing — he is an activist for LGBTQIA+ rights — and part of what makes Gordo’s story so compelling.

The young Gordo is very much aware that he is different from those around him. He knows he is not like most of the other boys in the camp. This can be seen, for example, in the story “El Gordo,” where the protagonist gets boxing gear as a gift from his father, who is hoping to make him more masculine. In the interaction between the two characters, Gordo is worried about doing something wrong — that is, acting feminine — to make his father upset. However, he does not have the language to explain why people react to him in a certain way. At some moments in the book, the character tells us he is not a “real boy” and a “sissy,” the latter introduced into the narrative not by Gordo himself, but by his foil, the slightly older Cesar, in “The Nasty Book Wars.”

A typical model of what a heterosexual boy is expected to be, the character of Cesar is employed by Cortez as a juxtaposition to Gordo, the former’s stereotypical masculinity reinforcing the latter’s out-of-placeness. This strategy is clear in “The Nasty Book Wars,” where boys are pitted against girls for the ownership of several pornographic magazines left behind by one of the migrant workers. As the only one who understands what the magazines are, Cesar refutes Gordo’s suggestion that they should all share them as a “sissy idea,” seeing that the books weren’t “for girls, they’re for MEN!” This is the very first time the word is used to refer to Gordo, and later in the story, Gordo adopts the term as he tells us how the conflict between the boys and the girls was “an excruciating binary to a sissy boy like me.”

Linguists say that we access the world through language, and as such, there is tremendous importance and power in being able to name something. It is, therefore, highly significant that it is Cesar, the “masculine boy,” who puts a word, even if indirectly, to what is supposedly wrong with Gordo and his queerness. For effeminate gay men, sexuality is not discovered at the moment of attraction to other men as most suppose, but early in childhood when the world names them as different and deserving of exclusion due to their traits. It is this naming process that we see in Gordo’s discovery of his sexuality through others’ reactions to him. In another story, “Alex,” the term “sissy” comes back up once again, this time used much more emphatically as a slightly older Gordo states that “Sylvie and a bunch of boys at school, they’re always telling me I’m a sissy. Everything I do is a problem: the way I laugh, throw a baseball, or run. They tell me I talk like a big fat girl . . . It’s not a good idea to be different.”

Cortez himself is queer, and Gordo could be classified as autofiction. The author has previously stated in interviews that he is a writer of limited imagination, building stories on his memories and feeling no need to invent. In Gordo, he delves into his childhood in San Juan Bautista and Watsonville. The autobiographical characteristics of the book are of interest when we consider the other ways Cortez explores masculinity throughout the narratives. Through the young narrator’s perspective, Cortez gives us glimpses of the behavior of other men in the camp, touching on topics like domestic abuse and alcoholism. However, there is a certain tenderness in how the author writes about these men that still allows them their humanity. Consequently, the reader does not dismiss them as monsters due to their actions, but may, in fact, feel some sort of pity. This could very well be because Cortez rarely chooses to look head on at the violence perpetrated by the men. For example, we know that Gordon’s father is abusive, but we are not privy to scenes where the mother is hit. Gordo is not a book where Cortez looks unflinchingly at the violence that surrounded him as a child.

But the violence is there. Children are hit by their parents. Wives by their husbands. Queer men by homophobes. One of the most shocking scenes in the book may be when Cesar slaps Tiny, the youngest girl in the friend group, across the face in the aforementioned “The Nasty Book Wars,” showing how that sort of abuse is passed down through generations. There is also the violence of the state: the Immigration and Naturalization Services that come in to hunt migrants for deportation and the poverty surrounding the workers. Yet, the violence does not take over the tone of the stories. Gordo’s point of view, his observant but naïve perspective, seems to filter much of the violence for the reader. This is where Cortez’s use of humor comes in. The heaviness of some topics in the book can lose part of its weight due to Gordo’s young point of view. “The Nasty Book Wars,” for example, ends with the children’s grandmothers running across the camp after scattered pages of the magazine. The image of elderly women trying to catch pornographic photos blowing in the wind lightens up much of the violent tone built up by the narrative.

There is much in Gordo that could feel bleak. The stories of a young, Mexican American boy living in a migrant camp, amongst violence, homophobia, and poverty should not feel hopeful. Yet it does. Cortez seems far less interested in exploring trauma than people’s resilience. Gordo’s childish perspective allows Cortez to tackle serious issues with levity and humor, giving the impression that laughter at the face of adversity may be a form of resilience. In that sense, what stays with the reader is not the characters’ pain or the violence around them, but the forms they find to survive.

Allysson Casais is a PhD student in Comparative Literature at Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brazil.

This post may contain affiliate links.