photo by Daniel Schechner

Bianca Stone reads to me like the master of a 21st century anxiety that is both frustratingly material and absurdly metaphysical: as she puts it in “The Way Things Were Up Until Now,” “A serious drama in a cosmic joke.” When I read her poetry, I laughing as often as I am in pain, if those feelings are not already simultaneous. What Is Otherwise Infinite is a collection that seeks to erase horizons and any other lines left between us and what is sublime, at the same time as it is a book about the acute pain of even sitting at a table doing something as seemingly meaningless and nonetheless difficult as eating to sustain oneself, and how funny that all is. Ha ha.

I felt very lucky to chat with Bianca Stone over the phone just before the new year, despite the ambulance. And while in text it might read dreadfully serious, know that I had to contain myself to only two instances of [Laughs].

Kyle Francis Williams: I’d love to start by asking where this collection started. It was interesting to reread Moebius Strip Club of Grief into What is Otherwise Infinite because Moebius has this literalized central project, whereas this book might not look that way.

Bianca Stone: Moebius looks more centralized, because I was having fun with an idea (this “strip club”, a very tangible topography, and in my mind I felt compelled by the was ancient myths create metaphorical typographies) but I feel that I ended up editing this book with more intention around its themes. Every book I’ve written has been a learning experience in what it means to have a book of poetry–a genre which rejects the logical structures of narrative and a at the same time explores themes with intentionality and narrative arc. It takes trust and willingness to be surprised by yourself, as well as have evolving goals held in mind. It usually starts with me pretending I have a book. There’s an element of hubris here. I just had a handful of finished poems, and whole lot of unfinished poems, and a desire to move towards something I couldn’t quite put my finger on: I start my books by desiring to understand something I don’t understand. I’ll look at my poems I have and assemble something like the chalk outline of a book, and proceed filling in the body. From there I can develop the themes I’m working with. I had only some idea what this book was going to be about–I was going through an experience of trying to figure out how to be happy, how to live. And this fantasy of fixing something that felt wrong; this spiritual in a state of dying, and desiring full-death and resurrection.

It’s really interesting to hear about how a collection comes together for you. I’d love to ask you about how you structured this one. There are really a lot of epigraphs, for instance, that reinforce the four partitions of the book.

Well, the final book actually doesn’t have most of the epigraphs. We waited too long to get permission. The only one that remains is from Milton and Coleridge because they’re copyright free–and I did really want the Levis quote in Psychodynamic speech, so I hauled ass on getting permission. I will say, though, that I don’t usually have epigraphs. This time I wanted to experiment with them, and felt really excited about the process of research and quote collection that I’ve gotten into. I’m glad some of those epigraphs came out. The book really evolved away from some of the quotes that were there. There was a Goethe quote about nature—the book was originally called Human Nature—and I thought it would be more about Man and Nature more directly. In the end, there aren’t really a lot of plants in the book.

Even without the epigraphs, there are a lot of references to other writers in these poems, and the conversations I’m having with other writers became really important to me. Interestingly, a lot of them are men. I think there was something in that. I wanted to figure out human nature as much as I can, to constantly ask, Why are we like this? It’s important then to look back at other writers and thinkers and philosophers and scientists and whatnot asking the same question.

I’m glad you brought up the references and the conversational nature of these poems. I know you’re a poet who is really interested in histories of the canon—religious canon, literary canon, and “the oral tradition of screaming” as you write in “A Queen’s Ransom.” One sequence, “Rhyme of the Ancient Mariners” into “O Wedding Guest!” tracks Coleridge to Dickinson. And it is interesting that many of the references are to men, especially considering a poem like “Beatrices” that is focused on the woman the man writes about. How are you thinking about structuring poems around conversations with other texts?

So much poetry is based on allusion, and I think Dante is one of the most prominent allusions in poetry—and other genres—period. Then, Coleridge and the Romantics ended up being really important to the book because they too were at this cultural moment of trying to see themselves in nature again, asking, How can I find myself in this vista? It was a question of melding human and nature, a meditation on our illusory separation from nature, and a desire to get back some connection to the world that should never have been and never really was lost.

“Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and the Comedy are poems about the poet facing their regrets, encountering parts of themselves they don’t really want to look at, and embarking on these very clear journeys through something. That’s all something this book is doing too.

My last book was very concerned with women. I grew up in a family of women, and felt I had to focus on women as higher where men were lesser and not to be trusted. At the same time, there were a lot of contradictions my family and I lived in. This book finally demanded me to deal with the male part of me, and with my relationship to men, more directly. I say “directly,” but, you know, directly at an Emily Dickinson “slant.” I was trying to understand something about men in this book, and I didn’t fully realize what that meant, but it was happening nonetheless.

I’d love to zoom in on one poem as a way to talk about different parts of the book. I really love “Psychodynamic Motivational Speech,” and I think it’s a good poem through which to ask you some broader questions about the collection. It’s the longest poem here at seven pages, and it’s also right in the middle of the book. Could we start by talking about where this poem came from?

Absolutely. It’s a good poem to talk about, too, because it’s really representative of how I write my poems. It started off as a much shorter, one page poem called “God’s Motivational Speech.” And it was much more of a motivational speech. But only some of the lines from that draft survived. I couldn’t get the poem right, and I couldn’t let it go. It felt important to me. Writing these poems was largely an attempt to understand something, and an attempt to get better. I was in a lot of pain. I’ve always struggled with depression and anxiety, and it was reaching a really intense pitch. I was trying to help myself—because I could not get help from the New York City healthcare system, no matter how hard I tried.

There’s an ambulance going by my window here in Brooklyn.

I hear it. So I turned toward a lot of motivational self-help stuff that I’d never considered ever before. I tried really hard to get that to work for me, but it turned into this intense form of masochism where I would try to motivate myself and feel like a failure doing it—saying every day that today is going to be different, and then saying fuck it, that today isn’t going to be any different, tomorrow’s going to be different. At the same time as this motivational stuff came up, religion came up. I was trying to quit drinking and that lead me to this interest in an ancient Christian mysticism. Even still, none of it was helping. It was getting worse.

Eventually—during the pandemic—I hit a bottom and tried therapy again, ending up in psychodynamic therapy. It’s a more affective and active therapy than something more common like CBT. My whole life has changed since. I edited this manuscript during quarantine, while heading into psychodynamic therapy every week, and this poem came out of a conversation I was having with multiple areas of myself, from back when this poem first began, from my past before then, through now, and to my potential future. It is a poem that isn’t the end of the experience—there is no resolution—but it shows the potential, and challenges me to interact with the unconscious, unthinkable thoughts and experiences that I was and am going through still.

This poem has some of my favorite line breaks in the book. Like:

The delicate edges. I know

that shame

lessens the value of things

In general, I love your breaks. They often feel thrilling and surprising. How do you break a line?

Breaking a line is a wonderful, wonderful thing that poets get to do. I feel so lucky that I get to break lines, and I have a lot of fun with it. Sometimes it comes easily and naturally, and other times you fuss a lot over it. Then it’s different in your head than it is out loud; it will look right on the page but won’t sound quite right when you read it out loud. And there’s always an element of line breaks that is not quite right—that’s what makes them so great. Line breaks are disruptions and imperfections, complicating things.

Line breaks are important for the momentum of a poem. They add a certain jolt that can make things move more quickly; a poem like “Psychodynamic Motivation Speech” has a very fast pace to it, and the line breaks help with that. Breaks also add another layer of meaning, whether to a single word or a phrase. You can upend expectations of what will be coming in the next line. You can heighten drama, humor.

I think of each line as its own unit, almost its own poem on the page. Some younger poets won’t think of breaks that way—will say they don’t know where or how to break the line. But line breaks are your opportunity. Half the creation of the poem is breaking the line. It’s not a trick you have to learn, it’s all about you: where your brain is going, where your breath is going. Breaks make the reader breathe the way you breath. They add an element of negative capability into the poem by having a blank space suddenly interrupt things; that break is where the reader makes the meaning of the poem, in that empty space that is air, breath, or white space.

On that note of heightening humor and drama, this poem is so good at another thing I love your poetry for, which is this complete control over the modulation of tone. This conversational “I mean” before

what do I know about shame,

being only the madness you leaped from?

Or a line like

That’s purgatory, baby.

I think these moments are astounding. You can dip into humor then spring suddenly into the highest metaphysical plane. Can you talk about that balance and movement?

I love a wry humor in my poetry. I’ve always thought of poets as jesters or clowns. Not because we’re silly and make dumb jokes—though we do—but, historically, there’s something about the fool that enables them to tell harsh truths that are difficult for people to hear, but through humor make people more apt to listen to those truths and be able to handle it.

Humor can be very frightening, too. Clowns can be terrifying. The crossroad of humor and darkness is an intriguing place to be. It’s unnerving but you can’t look away. I want people to listen. I want people to hear what I’m saying, and not look away. But I myself can’t bear it without an element of humor. That absurdity is part of the human condition. I forget that all the time, but when I remember that it’s also all so ridiculous, I feel such relief from the anxiety of being in it.

At the same time, I believe in making big statements about beautiful things and life that are deadly serious. I want to appreciate a high level of truth-seeking and understanding and epiphany. And you might think, Who am I to say these things? But who is anybody to say any of these things? Nobody is more equipped than anybody else, actually. In poetry you stumble onto those truths. You don’t sit down with your beautiful thoughts, you write a bunch of bullshit and then, all of a sudden, a thought will come to you that feels true and right. And just like telling a joke is a relief, saying a truth is a relief. Saying something that is true but hard to articulate is a great relief, and I want to write poetry that helps relieve people of the existential dread of seeming reality we’re surrounded by all the time. That’s not all there is. [Laughs.] It’s really about an infinite nature that we ignore!

Browsing Netflix last night, I ended up watching Cosmos with Neil DeGrasse Tyson, and the first episode is that poor Italian monk Bruno, who read Copernicus in his closet and was banished from the monastery. He didn’t care that the inquisition was everywhere; he went around talking about his belief that God is infinite, that there are infinite worlds in the universe. And it wasn’t hell. It was beauty, even then. And it’s true! I’m trying to get at this—the infinite possibility and nature of our being alive—through all these different tones, where tones and words are all we have to work with.

I love how, even in answering that question, we got from Netflix to the sublime. I really appreciate that.

That’s what I’m talking about! I can’t only talk about the infinite. I’m not a zen master who can just meditate on nothingness, I have to talk about clowns too.

I love that. You said this poem went through a lot of different versions, all dealing with who you were at various stages of writing this poem. That all is still here in this poem, the way it doubles and triples back on the “I,” in a way that makes the poem seem really suspicious of that lyric “I.” A lot of the book felt to me like you were turning away from the lyric “I,” or, as you put it in “The Ostensible Psychic Wound,” from “the old Bianca,” as it were. Does that ring true? Is there something about the lyric “I” you were trying to get away from with this book?

Yes and no. I was exploring different ideas of who I thought I was and am, and honoring the fact that there are multiple selves within the self. There isn’t just one self. Even the way we talk about poetry having a speaker and a writer is an indication of a self that is not the self. I was pushing that. It’s interesting in this poem. The first draft, it was God talking. And then it was, I guess, my therapist talking. Then me talking. But what is therapy but them mirroring you, mirroring what you’re saying and doing, and trying to get you to realize the mirror? That’s exactly what this poem is doing. It’s showing multiple selves, as well as the potential self—the potential self that is also the reader, the therapist on the other side of the room. What fascinates me so much about therapy in regards to poetry is that mirrors the situation of the poet and reader, and the poet and the speaker. That mirroring is exactly what’s happening. The therapist has their own inner world, and they are active in the session too, just like the reader out there is active in the poem while their inner world and their inner selves get all wrapped up in it too.

It’s like learning to have a psychoanalytic relationship with yourself, learning to talk with your multiple selves. You might be in a psychological state of depression, and that will feel like the only thing. But if you can get into another psychological state, you can converse with that depressive state and learn a lot. That’s what happens in poems. It’s you conversing with other versions of yourself—and then the reader comes in to have the conversation too.

This collection, and what you’re saying, feels deeply invested in the compositional nature of the self and reality. In “Illuminations” you wrote,

Human nature is bifolios, versos, even blank pages

with preparatory rulings for the scribes, never painted upon.

Little books of suffering saints and resurrections.

That’s what we are.

And then in “The Human Good,” you wrote this absolutely hilarious line,

We settle in to read aloud the linguistic eloquence of obscure

contemporary fucking poetry.

So even while this collection has that investment in the compositional nature of things, it feels deeply suspicious of that, and what poetry can do or what poetry can be used for. I felt a struggle between various poems over what would win out. Is that a newer suspicion of yours, or one you’ve always had? Is there a balance between this poetic suspicion and the urge to poetry?

I think the suspicion comes from this desire to find answers, and how dangerous that desire can be. I have a deep suspicion of the feeling of inadequacy—that if it weren’t for this feeling of not being enough, I would be infinite. I didn’t think of it as a suspicion of poetry, but it is in a way. I put poetry on a pedestal 99% of the time, and I’m suspicious of that. I’m worried about what that means. It’s always imperfect; it never reaches quite the height you want it to. But it should be that way. If you wrote a perfect poem, that would be the end. There would be nowhere forward to go anymore.

I want more for us, as a species and a culture. I want us to appreciate what poetry does, what the poetic state does. But I don’t know what we’re capable of achieving here, because we’re so good at messing it up. We’re so good at missing the point. I want to have hope, but I’m also suspicious of all hopeful things. [Laughs.]

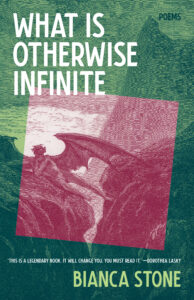

What is Otherwise Infinite

Bianca Stone

Tin House

January 2022

Kyle Francis Williams is a writer living in Brooklyn. He is an MFA Candidate at UT Austin’s Michener Center and Interviews Editor for Full Stop. His fiction has appeared in A Public Space, Hobart, and The Nervous Breakdown. He is on Twitter @kylefwill.

This post may contain affiliate links.