[Wakefield Press; 2020]

Tr. from the French by William Kulik and Serena Shanken Skwersky.

During her lifetime, artist Leonor Fini resisted simplistic categorization. She resented being grouped with the Surrealists, ardently denouncing the views of their leader, André Breton, as misogynistic. Although she shared the Surrealists’ interest in dreams and the subconscious, she strayed from their depiction of binaristic female archetypes — devouring monster or docile girl-child — and instead upheld subversive gender roles: regal, if not freakish, women positioned in mythological scenes dominate her work, and when men appear, they generally function as passive receptacles for female desire. Her subjects tend to be some sort of human-animal hybrid, and more often than not, they are surrounded by imagery of death and decay. In her personal life, she rejected the staid conventions of womanhood, forming a polyamorous family comprised of two men, zero kids, and over a dozen cats.

Evidently, she took metamorphosis seriously, believing in its potential to liberate the self from the shackles of conformism, opening channels towards a truer, richer ontology. But she also acknowledged its humorous side — the awkward growing pains that must be navigated in the process of evolution. Her paintings embrace wonky proportions, unwieldy limbs, and discontinuity; but they never lapse into farce, retaining a defiant elegance. Fini embodied this elusive balance herself — both oddball and queen, commanding attention without compromising respect. Her commitment to metamorphoses and appreciation for the theatrical lead her to pursue a variety of creative endeavors. She designed fantastical costumes for ballets, operas, plays, and movies. And, of course, she wrote fiction.

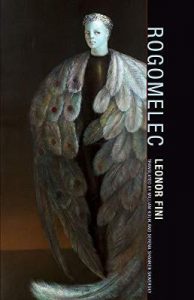

Rogomelec is Fini’s third novel, published in French in 1979. It is inspired, presumably, by her painting of the same name completed a year prior. The artwork features a stately winged figure, adorned with a silver crown; “Rogomelec,” as the narrator of the book instructs, means “he who stones the king.” This definition is immediately thrown into suspicion by a peripheral character, who refutes their claim, and the issue of etymology is never resolved.

Like her previous novels, Moumour (1976) and L’Oneiropompe (1978), Rogomelec is set in an island monastery modeled after a Franciscan monastery in Corsica, to which Fini relocated every summer. All of her literary contributions feature classic motifs from her visual oeuvre: mythological creatures, gender ambiguity, and free-flowing desire. But Rogomelec is dark in tenor, breaking from the utopic gestures of her previous works. This is not to say that the novel is cynical; cynicism necessitates an interpretable message, and Rogomelec is uninterested in coherency. Rather, it is interested in moments — in particular, moments of unease that signal eminent transformation. Rogomelec is a collection of surrealist vignettes, conjoined by non-sequiturs; the sum of these moments doesn’t amount to a discernible theme, but it does convey a feeling, offer an experience. The novel is opaque, and that’s how Fini likes it.

Speaking to Xaviere Gauthier in 1973, as included in the book’s introduction, Fini advises that spectators approach a work of art with openness and curiosity, engaging with it on its own terms:

“It is difficult to understand a work. It must be left to act on its own, whether to fascinate or disgust. The spectator must allow himself to contemplate — to submit, if you like — and, if he is attracted, called by a painting, then this is because there is an element that exists in him (a sensation, a presence, a remembrance) that remains untranslatable into words.”

Bearing her philosophy in mind, it is futile to treat Rogomelec like a key, like a cheat sheet for the questions her paintings pose. The written form — here and in general — doesn’t ensure clarity; language inevitably breaks down; gaps in communication materialize, regardless of intent. Rogomelec exists in that gap, swimming in the vast expanse of the illogical, the askew, and the uncanny. Given the onus of communication that language is particularly held to, non-sequiturs are arguably more distinct in her writing than in her paintings. So perhaps, in this way, the book does provide an answer of sorts — namely, to stop looking for an answer and allow for logic to bend where the senses expand.

However, if the reader chooses to persist in identifying an explanation, it could be said that Rogomelec is a cautionary tale about vacations. The novella opens with the unnamed, ungendered narrator scolding themselves for going against their better judgment and succumbing to travel’s call: “That I should know enough to stay home, to avoid traveling in these barbaric times, the terrible hustle and bustle, the indignities of so-called ‘vacations.’” Many of the indignities the narrator undergoes are familiar to the adventurous reader: logistically nightmarish journeys, unwelcome encounters with opportunistic strangers, and surprise illnesses borne from a foreign ecosystem. But the heart of the book resides in unfamiliarity. That the narrative arc of the book is simple — the narrator embarks on a journey and returns home shaken by what they’ve witnessed — does little to temper the weirdness that is Rogomelec.

Absurd occurrences begin immediately, escalating in frequency and severity as the narrator arrives on the titular island, relenting only with their hurried departure. The primary draw of the destination is a decrepit monastery-turned-sanitorium, where monks pedal a hallucinogenic “cure” comprised of plants and flowers. (What precisely it is that the cure treats is never addressed.) The concoction carries the narrator off into a pleasantly disorienting fugue state and they pass their days oblivious to space and time, reliant upon the “kindness” of strangers; residents, with insidious generoisty, offer to undress and bathe the incapacitated narrator. These acts of caretaking read as invasive and, at times, erotic — insofar as they’re propped up by a significant power imbalance. The narrator bears these invasions agreeably at first, but soon tires of total dependency.

As their vacation progresses, they home in on the king of Rogomelec as their tether to reality: a problem to be solved, requiring a good degree of focus and purpose. Vaguely apprehensive, the narrator observes the residents’ frenetic preparations for his annual celebration; although the king is reclusive, he reigns omniscient within the public’s imagination. Then comes the sobering violence of clarity. At the ceremony, the narrator witnesses a horrifying scene involving the king, confirming their nascent suspicions about the “utopia.” It’s also possible that the scene was imagined, symptomatic of a bad trip. Regardless, they flee Rogomelec, recovering a sense of autonomy on their departure.

The disquieting tale unfolds over just twenty pages of written text. Fini’s illustrations punctuate the text, offering portraits of the entities introduced. Her writing is accordingly compact: astringent, sparse, yet expressive. At no point does she intervene on behalf of the narrator, providing neither psychological nor emotional insight. And at no point does she ascribe character evaluations. Instead, Fini relays the narrator’s experiences and reactions, unfiltered and unmediated.

She does, however, use the narrator to underscore the slippery process of writing and world-building. At the dawn of their journey, the narrator questions the presence of those around them: “Were they, too, voyagers, or had they been summoned by a simple word?” Asked another way: Do these travelers exist outside of the narrative? Or are they animated solely through authorial recognition? (It must be said that, as a genre, Surrealism lends itself quite well to solipsism.) Later on, they reflect upon the monk who administered their “treatment,” stumbling to grasp and articulate his being: “He was like a flying fox at sundown . . . But then, no, no; it was no longer the flying fox at sunset, but rather Xenia who had seen me from afar, who had come to me, bringing a huge bunch of grapes.” The narrator, under the influence of the monk’s psychoactive elixir, loses their grip on both reality and language; they are forced to abort their concise simile and stagger through multiple clauses.

Here, and throughout the entirety of this book, it seems Fini is suggesting that at any moment the writer, or the artist, can lose their thread and, just as quickly, find a new one. That the threads may lack a cogent connection need not be accounted for. Every thread — every moment — is a world unto itself, open to endless interpretation; and it is telling that the narrator’s jolt to reality coincides with the first (and last) significant point of plot development. We tell ourselves stories in order to live, but we also do the reverse. Rogomelec posits life beyond storytelling as unsustainable — edging towards catatonia when unduly prolonged — but also as vital, enriching, and worthy of experience. And so it is with art too.

Caroline Reagan reads and writes in New York City.

This post may contain affiliate links.