Aimee Parkison’s staggering novel, Sister Séance (Kernpunkt Press, October 2021) merges the real horrors of slavery and the Civil War with supernatural horrors of ghosts and ghoulish visions: mutilations and amputations; veiled faces and entrails. The book, her sixth, takes place in 1865 Concord, Massachusetts, on Halloween, when guests converge at a traditional “dumb supper,” where everyone must express their wants and needs without speaking aloud.

Unsurprisingly—and mercifully—Sister Séance is not a conventional historical horror story, though history and horror do figure prominently. At its core lurks a hindsight-to-foresight examination of feminism, racism, superstition, and the violence of war: human inhumanity to humans. Yet Parkison doesn’t cede compassion; each character is wrought with tremendous precision and empathy. Vivid descriptions and meaningful dialog help raise the dead, perhaps not incorruptible but certainly unforgettable.

Parkison has always boldly experimented with language and subject matter in ways that continue to astonish me, and many others. An abbreviated list of her awards reveals an FC2 Catherine Doctorow Innovative Fiction Prize, Christopher Isherwood Fellowship, Kurt Vonnegut Prize, a North Carolina Arts Council Fellowship, and William Faulkner Literary Competition Prize for the Novel. Sister Séance was supported by an American Antiquarian Society William Randolph Hearst Creative Artists Fellowship.

I’ve known Parkison for years, since I interviewed her for a podcast at the 2008 &NOW Literary Festival of Innovative Writing where even then she insisted, “I want readers to feel connected to that suffering in a way that they can empathize with it.” All quotes prefacing my questions are from Sister Séance.

“It is our duty to properly mourn the dead. And create beauty out of pain.”

Di Blasi: The horror genre, in literature and film, has the potential to reveal humanity’s deepest fears and most primitive impulses. For me, your writing has always been far more than surface, always an exploration of the dirt and dried blood under humanity’s fingernails. What was your primary objective in researching and writing this novel? How did you maintain that objective through the creative process—or did it mutate the deeper you delved?

Parkison: I didn’t set out to write a horror novel. Not at first. The more I researched, the more I realized what the project had to be. It was based on historical research, and that part of our country’s history is full of horrors—physical, psychological, mental, and spiritual. Creatively, writing Sister Séance was informed by a mutating objective. The more I researched, the more I learned, the more the novel evolved. It took more than ten years to bring it all together. I found odd connections between Victorian America’s obsession with Spiritualism and courtship. Death was everywhere. So were wounds.

The country was full of wounded men, many amputees, returned from fighting the Civil War and many considered “no longer whole” due to their missing limbs. There were also the psychological wounds of war for mourners who had lost loved ones at a time when people believed in “good death” and “bad death.” Good death was dying at home in peace with loved ones near. Bad death was dying alone in pain, far from home, like a soldier in battle. That’s why Spiritualism became so prevalent—it was a final chance to contact the dead who had been suddenly lost.

“All hands joined a chain.”

Your diverse cast of characters demonstrates how wide suffering can bleed, from person to person, generation to generation, grief rippling and overlapping—the haunting legacy of slavery and the Civil War which remains the bloodiest in American history. One of the sentences that stays with me: “Every amputation was a story waiting to be told, a sort of mystery, he supposed, and wounded men bled riddles because a soldier’s body belonged to everyone.” Replace “soldier’s body” with “slave’s body” and the message resonates even more profoundly. Willa’s amputation, for example, is self-inflicted, a mutilation to reduce her worth as a child on the auction block. Her referring to her amputated hand in the third person is apt, because Sister Séance is also told through the appearance of hands. Tell me more about the development of this symbolism.

Yes! Hands are everywhere in the novel. Their symbolism is connected to the novel’s theme of nonverbal communication. My characters are bound by the unsaid in a tenuous web of secrets. As subtext, hands are constantly unweaving and destroying this web of secrets by revealing what characters don’t dare reveal through words.

Willa, a former slave, chops off her own hand to save herself from being sold by slave traders. Sampson Redlaw, a wounded veteran who fought in the Civil War, lost a hand due to amputation after a wound in battle. Hands of the living, hands of the dead, dematerialized hands, and amputated hands are part of the setting delicately preserving the fragile web of all the “polite” society wanted to leave unspoken.

Dancing hands, lost hands reunited with their former owners, enslaved hands, stolen hands, freed hands, captured and possessed hands, loving hands, gloved hands, naked hands, bloody hands, wounded hands, strong hands, dainty hands, coarse hands, filthy hands, delicate hands, men’s hands and women’s hands and children’s hands, hands of the living and hands of the dead, hands delivering babies, burying the dead, and even hands welcoming or hiding ghost babies.

“I will not abuse my position to indulge in sexual contacts with the bodies of women or of men, whether they be freemen or enslaved.”

Debates continue to swirl around the notion that writers should “stay in their lane” and avoid penning a literary work with characters of a different race, culture, sexual preference, and/or gender. How do you respond to those who might condemn you as a white woman writing a historical novel whose characters include enslaved people?

A prominent theme of the novel is white guilt. It was impossible to write about Whiteness without writing about Blackness, and it was impossible to write about the Civil War and its aftermath without writing about slavery.

Historically, it was impossible to write about women without writing about men. While all whites benefited from slavery due to the economic conditions, white women were in a much different situation than white men. Unable to vote, white women were economically, politically, physically, and socially controlled by white men during that time in history. Traditionally viewed as the property of white men, white women had to do something philosophically impossible to be protected in society, to be seen as “virtuous” while passively taking on the guilt of their husbands and fathers, whom the government said should speak for them.

“The spirit of one who has died will join us only if we remain silent.”

Love and trauma collide and overlap in Sister Séance. As in life, they blur, coalesce, separate, blur again. As an experimental writer, like you, I read the Invisible Guest seated at the head of the dumb supper table as both you (writer/conductor) and me (reader) who watches events unfold and in so doing tries to understand her own fluctuating role in existential narratives. Are we the mute invisible guests of our lovely and traumatic histories?

We’re all guests of our time. Our invitation to “the party” of life and the particular party we attend is related to our birth and our status, or lack of status, in society. Perhaps only those who live a very long time are wise enough to understand what it means to have been a guest at the party. Over time, most of us are invisible because to die is to be forgotten.

In some ways, we are all powerless observers, all the more because we usually don’t appreciate what was lovely, terrible, ugly, or beautiful until it’s lost because we don’t start to “read” our own stories until we’re near the ending. We don’t understand the trauma we’ve experienced, witnessed, or participated in when it’s close to us. As a culture, our notions and understandings of shared evils like sexism, slavery, war, and racism are evolving. Usually, by the time we have realized the significance of what we’ve seen and what we’ve been party to, it’s too late.

“Sweets and apples hung from strings above doorways.”

You’ve won quite a few awards and fellowships because your writing is beautifully idiosyncratic. As Stephen Graham Jones writes in the foreword to your story collection, Refrigerated Music for a Gleaming Woman: “The best books leave you asking a lot of questions. The best books strand you in the doorway, just holding on, not wanting to leave where you know but being sucked through to this new place all the same.” And yet, the majority of readers won’t let go of the door jamb. They cling to writing that, like partisan politics, never challenges their assumptions and thus leaves them stagnating intellectually and emotionally. As a creative writing professor in Oklahoma, the state where you grew up, how do you direct younger readers toward destinations they might otherwise avoid?

I think that’s life and reading in a nutshell—the majority of people, most readers, don’t want to let go of what’s safe, what’s familiar. In some ways, I guess all of us are guilty of holding onto our door jambs, either in life or in the imagination. Sometimes in life, you hold on to survive. Sometimes what’s outside the door isn’t safe or welcoming. That’s why fiction is so necessary—it’s a place where you can let go of the door without letting go of the door.

In writing, you create the door and then you can create something new by letting go of the door or by showing the door isn’t really a door. But you have to take your reader on that journey, and to do that, you have to capture their imagination first.

Holding onto the familiar can be the death of art. It can also be very boring. As a reader, I have little patience for any fiction that feels too safe, too familiar. I need something to surprise me in order to draw me in.

Teaching at Oklahoma State is like teaching almost anywhere in the nation except that the cost of living is so good here. The students come from all over. We have a graduate MFA and PhD program in creative writing that draws writers nationally and internationally, so most graduate students I work with aren’t even from Oklahoma. The undergraduates, who are mostly local to the region of Oklahoma and Texas, often come to my classes wanting to explore artistically and are ready to be challenged and surprised. They’re in workshop for the journey of becoming writers, so are typically quite open to discovering and reading new things. It’s up to them to decide where they want to go and how to get there, though I’m constantly pointing out in my teaching that the journey to becoming a successful fiction writer starts with becoming a reader of the kind of prose you want to write.

“The possibilities spun wildly.”

It seems to me that the longer—as in years—we write into the unknown and perhaps unknowable, the further away we move from mainstream expectations of what literature is and, dare I say, what the publishing industry demands literature be—i.e., “marketable.” In an ideal world, artistic growth would be rewarded, not penalized. An age-old conundrum: the writer as artist vs. the writer as author; the immense freedom in being alone in the wilderness of our creative minds vs. the loneliness of becoming an outlier, a sense of shouting into an exponentially expanding void. (Thank goodness, literally, for small presses and intrepid journals, smart publishers and courageous editors, curious and ambitious readers.) How do you balance what sometimes feels like a teeter-totter built for one?

I think some of it can be blamed on agents. Since agents only make money if the writer’s work makes money, they only want “marketable” writing, which does not typically mean art, though in some cases it can if the art happens to be what’s marketable at the moment.

Small presses, journals, and all nonprofit presses are pretty much homes for the writer who is an artist, since nonprofit publishers are not trying to make money off writers. Since they are free from worries about profit and marketability, small presses and nonprofits are concerned with publishing as curation of artistic work. This is why small press and nonprofit presses often keep books in print so much longer than big houses who tend to give up on titles that do not sell well.

It’s lonely and freeing to be an outlier. My writing makes the choice for me. I follow language, character, form, story, experiment to see where that takes me rather than following an audience to see where the audience wants to go. If the writing is “working,” the language takes me somewhere.

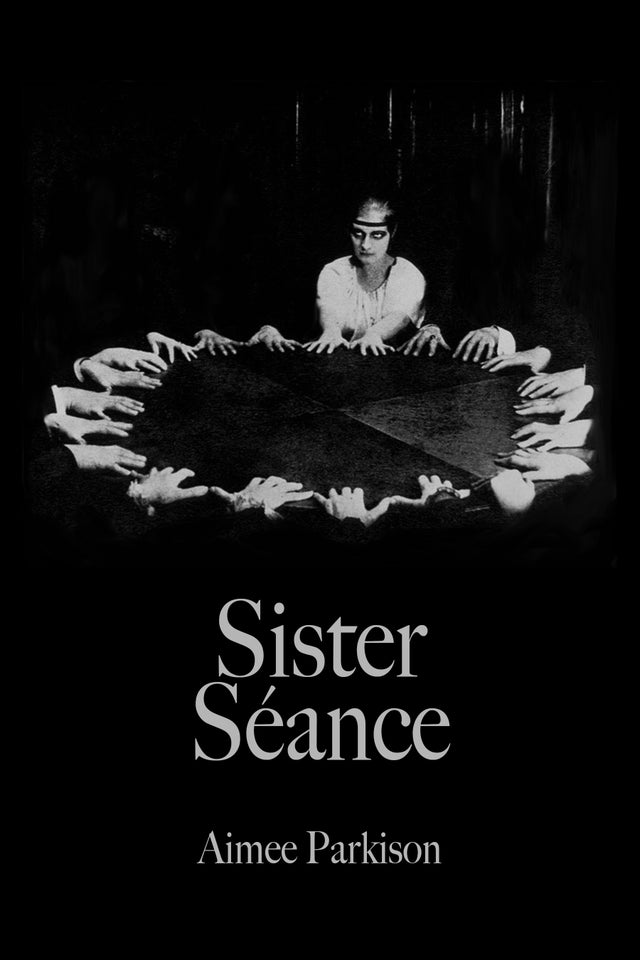

Sister Séance

Aimee Parkison

Kernpunkt Press

October 2021

Debra Di Blasi is an award-winning multi-genre author of 10 books, with prose and poetry published in anthologies of innovative literature and in prominent journals and reviews such as Copper Nickel, The Iowa Review, The Los Angeles Review, New Letters, New South Fiction, Notre Dame Review, Pleiades, Triquarterly, and many more. Notable awards include the 2019 C&R Press Nonfiction Award for her lyric memoir Selling the Farm: Descants from a Recollected Past, Thorpe Menn Literary Excellence Award for Drought (New Directions), Diagram Innovative Writing Award for ‘Quell the Mayhem Night,’ and a Christopher Isherwood Fellowship. She is a former book publisher, educator and art critic who continues to lecture on narrative forms in the literary and visual arts.

This post may contain affiliate links.