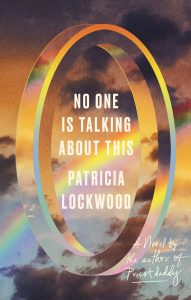

[Riverhead; 2021]

When I first encountered Patricia Lockwood in her spirited reappraisal of John Updike in the London Review of Books, it felt like a revelation. Insight, asperity, un-pompous erudition — the perfect potion, it seemed — spilled delightfully onto the page. Here was a writer worth watching.

A quick Internet search told me that I was late to the party, as she’d already established a reputation as a poet and author of an acclaimed memoir, Priestdaddy (2017), while publishing essays and cultural criticism. So the release of her first novel, No One Is Talking About This, was much-anticipated, not merely in terms of media buzz, but by real readers, by which I mean, of course, myself.

Written in fragments, the novel is divided into two sections, centered on an unnamed protagonist who is an Internet celebrity and expert on digital media, pursuing her career on the international lecture circuit. The first part depicts her as nervously at home in these elements, surveying the virtual landscape and the evolving virtual inscape while traversing the planet’s time zones. In all contexts, the Internet, Twitter et al. are collectively referred to as “the portal.”

The second part of the novel shifts to a crisis in the non-virtual world, where the protagonist’s sister experiences a harrowing pregnancy and the birth of a baby with a rare genetic disorder called Proteus syndrome. Born blind and suffering from a grave assortment of health issues, the infant survives only six months, but during her brief life, she inspires a deep, transformative love in the sisters.

The stark contrast between the two parts is crucial to the novel’s design. One could imagine the author riffing longer in the first part and writing a timely stand-alone “Internet novel.” As the narrator asserts, “All writing about the portal so far had a strong whiff of old white intellectuals being weird about the blues, with possible boner involvement.” Or, similarly, the author could have developed the second part into a memoir-inflected autofiction.

Instead, by presenting these contrasting parts as a whole, Lockwood attempts something more ambitious, formally speaking. Overall, I don’t think the novel succeeds — more about that later — but in its best moments, the stylized fragments of No One is Talking About This are original and compelling. Here, she conveys a perception of police violence:

The labored officious breathing of the policemen, which was never the breathing that stopped. The poreless plastic of nightsticks, the shields, the unstoppable jigsaw roll of tanks, the twitch of a muscle in her face where she used to smile at policemen . . .

Both visceral and minutely observed (“poreless plastic”), this description might lazily be described as “poetic” but that would miss the mark. Although the author is also a poet, her prose offers a welcome reminder that poetry has no monopoly on sensuous language. Some novelists write as if the bare pine aesthetic of an Ikea bookshelf has leached into their style; Lockwood wants nothing of this. Consider the passage when the protagonist meets her newborn niece:

All the worries about what a mind was fell away as soon as the baby was placed in her arms. A mind was merely something trying to make it in the world. The baby, like a soft pink machete, swung and chopped her way through the living leaves. A path was a path was a path was a path. A path was a person and a path was a mind, walk, chop, walk, chop.

Until this moment, the main character has been preoccupied with trying to capture the “communal stream-of-consciousness” of the portal. She chronicles its antic dippiness and aleatory profundity, while musing about its effects on fashion, language, politics, and consciousness itself. Many of these fragments are cleverly done, but they’re not exactly news. I was reminded of Jennifer Egan’s inclusion of a PowerPoint format in A Visit from the Goon Squad, which might have felt technically daring in 2011 but now, only a decade later, seems quaint. There’s a similar problem here, as web novelty is dated as soon as the pixel fades.

This problem is most palpable in fragments which rely less on wit than on a kind of whimsy. Lockwood’s frankness can be refreshing but sometimes her ear fails her. Words like butthole or ass are treated as cutely transgressive — there’s definitely a puritanical edge here — and the protagonist enjoys chuckling at her own jokes. Though she supposedly travels extensively, there are few cultural particulars as countries blend into a duty-free pudding, where everybody speaks English and there is scant intimation of places outside of a touristic comfort zone. The same is true of the portal: it’s a monolingual monolith. For all its expressed angst about current American political woes (racism, violence, Trump as “dictator,” etc.) or hip cringing at old pop culture (“Sweet Caroline”), the novel evinces an unwitting sort of American triumphalism.

Thus, the second part of No One is Talking About This provides a salutary jolt. Here, the protagonist finds herself utterly disarmed by a baby whose condition defies easy answers or facile questions about “what does this meme?” Another world beckons, full of menace and promise, as she feels attracted to the child.

“I can do something for her,” she tried to explain to her husband, when he asked why she kept flying back to Ohio on those rickety $98 flights that had recently been exposed as dangerous by Nightline. “A minute means something to her, more than it means to us. We don’t know how long she has — I can give them to her, I can give her my minutes.” Then, almost angrily, “What was I doing with them before?

Like an observer in a 21st century version of Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” she has concluded: you must change your life. Only in her case, the inspiration is not art but life itself, in one of its most challenging iterations. She becomes devoted to the baby, sharing with it as much life as she can. Songs, the sensation of a dog’s tongue on her body. Her own physical contact. And when the baby dies, there is the inevitable question of what it all meant. This is evoked in a conversation with a doctor:

The doctor took a bite of bagel and shaped his mouth the great word why. “When Jesus met the blind man, his disciples asked him why — was it the man’s sin, was it the sin of his parents? And Jesus said it was no one’s sin, that it happened so that God might move us forward, through and with and in that man.” Tears stood without falling in the doctor’s blue eyes; that is the medicine, she thought. “If I can do anything . . .” he said chokingly, with a slight amount of cream cheese in his mustache, which increased her love for the human race, which moved her forward through, with, in him, which was also for the glory of mankind.

This passage raises many questions about suffering and existence, and of course it’s not a flaw in a novel if these questions remain unanswerable or are selectively filtered through a character. Here and elsewhere the protagonist experiences an awakened love for humanity and a movement forward which is also for “the glory of mankind.” Her sister says of her valiant efforts with the dying child, “I would’ve done it for a million years.”

But here’s another question, largely unaddressed: how much can we instrumentalize the suffering of others? It is precisely the suffering of children that prompts Ivan Karamazov’s rebellion, his desire to “return the ticket.” Clearly Lockwood embraces another narrative, perhaps one of mystery (“Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth?” God tells Job), and that is indeed an answer with a long (and for some, venerable) history. But, in a novel couched in the religious terms that Lockwood is using, Ivan and his rebellious ilk ought to have at least been given a hearing, if only to be rejected. It would have been interesting to see how a writer of Lockwood’s talents would confront the question.

My first impression that Patricia Lockwood is a writer worth watching remains intact. But No One is Talking About This is an uneven performance. Its style cannot fix its gaps. The world of the portal described here is less a world than a province of the U.S.A. Its voice is powerful but unrelieved by other voices, by a readiness to put into question its own articulateness. That said, this is a wildly ambitious novel, so even a qualified success, or failure, is to its credit.

Charles Holdefer is an American writer based in Brussels. His work has appeared in the New England Review, North American Review, Chicago Quarterly Review and in the Pushcart Prize anthology. His latest book is AGITPROP FOR BEDTIME (stories) and his next novel, DON’T LOOK AT ME, will be released in 2021. Visit Charles at www.charlesholdefer.com

This post may contain affiliate links.