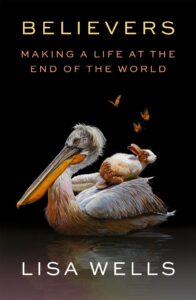

With her brilliant debut essay collection, Believers: Making a Life at the End of the World, prize-winning poet Lisa Wells proves herself a clear-eyed artist we can turn to in the end times. The collection pursues an impossible question: “The world is burning; how, then, shall we live?” Its eight essays offer intimate portraits of outliers hazarding an answer — by rewilding the desert with edible roots and wildflowers, by forming covenants with watersheds, by implementing Traditional Ecological Knowledge to rebuild a wildfire-resilient California — while also seeking meaning, purpose and redemption as civilization barrels toward the cliff-face. Shrewd, erudite, and soulful, Wells’s collection distinguishes itself from the growing body of “climate” nonfiction with its literary beauty; it’s worth reading for the lingering rhythm of Wells’s sentences alone.

With her brilliant debut essay collection, Believers: Making a Life at the End of the World, prize-winning poet Lisa Wells proves herself a clear-eyed artist we can turn to in the end times. The collection pursues an impossible question: “The world is burning; how, then, shall we live?” Its eight essays offer intimate portraits of outliers hazarding an answer — by rewilding the desert with edible roots and wildflowers, by forming covenants with watersheds, by implementing Traditional Ecological Knowledge to rebuild a wildfire-resilient California — while also seeking meaning, purpose and redemption as civilization barrels toward the cliff-face. Shrewd, erudite, and soulful, Wells’s collection distinguishes itself from the growing body of “climate” nonfiction with its literary beauty; it’s worth reading for the lingering rhythm of Wells’s sentences alone.

Wells and I spoke on her porch in Seattle, the same week the unprecedented so-called “heat dome” descended over the Pacific Northwest like the ghost of summer future. We discussed her days as a high-school dropout on a quest to end ecocide, the cosmologies and convictions of the people she chronicles, and why she writes toward beauty for beauty’s sake.

Believers is out 7/20, and I urge you to join Lisa Wells at one of her upcoming virtual events.

Alex Madison: In the book’s second essay, “On the Rise and Fall of a Teenage Idealist,” you describe yourself as the “the product of a particular microclimate” — having grown up working-poor in the Pacific Northwest in the 1990s, “a high school dropout . . . who happened to be coming of age in an epicenter of radical environmental and animal rights movements.”

I think it would be grounding for us to start by talking about your own first experience trying to answer the central question of your book: The world is burning; how, then, shall we live?

Lisa Wells: Well, the nutshell is that, when I was 15, my three best friends and I read Ishmael by Daniel Quinn, which is a classic novel amongst a particular subset of the population. I don’t need to recount the plot, but the argument is that what we take for granted as progress is actually the result of one culture taking over the world — one culture eradicating any form of life that stands in its path, or from which it can extract resources. Inevitably, this one culture is going to cause ecological collapse and, essentially, the end of the world, unless we all have an awakening about our connection to the earth and return to a sustainable hunter-gatherer-gardener-based lifestyle.

After this Daniel Quinn book, we read books by a man named Tom Brown Jr., who had a series of field guides to tracking and wilderness survival. But there was also a spiritual component that captivated us.

These books had a profound effect on me. The ideas in Ishmael felt revelatory. I was transformed like anyone who’s developed a fanatical relationship to a worldview. My friends and I dropped out of high school and ran away to wilderness survival school. We took the Greyhound bus across the country to New Jersey to study with Tom Brown, Jr.

What would you have said at the time about the vision you were hoping to realize, or the change you wanted to effect?

It sounds so pompous, but we felt that the collapse was imminent in 1998 or 1997, and we wanted to survive it. We wanted to attain the skills to help implement this revolution of sustainable cultures. We believed that civilization was going to collapse, that it was toxic and destructive and needed to end, and that everyone else around us was participating in an ecocide. We felt we needed to evangelize to them and raise their awareness.

It’s a little bit like if you ever had a friend who’s secular and then became born again. They want to save your soul, because they truly love you and believe that you’re going to burn in hell. We wanted people to be able to save themselves.

I wanted to start with that personal history, in part because I detected a coming-of-age throughline backgrounding the essays in the collection — your own and that of Peter, one of the friends who attended wilderness survival school with you.

You and Peter began this quest together, but your paths diverged. Peter remaining active within the world that you’re now considering from the outside, and one of your essays focuses on Peter, particularly his experiences as the “Urban Scout,” a performance art piece he enacted on the streets of Portland, in garb you described as “Max Max meets Ötzi the Iceman.” What set you and Peter in different directions?

Even though I was the most unforgiving and fundamentalist of us when we were kids, I was always drawn to art. While I was at the wilderness survival school, I really sucked at all of the skills. I would get frustrated and sit on the porch of our apartment and smoke cigarettes and read Allen Ginsberg. So it was like a classic experience of holding onto an ideal that really wasn’t corresponding in any way to my lived experience or my actual desires or talents.

Peter stuck with the skills — building shelters, weaving baskets, processing animal hides, that sort of stuff — as the Urban Scout, and now as part of an organization called Rewild Portland, which provides free community education around those skills, running summer camps for kids. And he also writes about rewilding quite a bit. I think the work that Peter does is really important, and he’s never strayed from it. He has a passion for this stuff. He loves to teach these skills. He loves to learn about archeology, loves to rabble-rouse and push on people. So he’s “following his bliss,” to use that probably corny Joseph Campbell phrase.

But a book is what I felt like I could contribute. I’ve spent all these years apprenticing myself to writing, and it seemed like the one thing I could do was serve as a translator or bridge from these pretty fringy insular subcultures to what I imagined to be a general reader.

The collection does introduce us to a whole cast of characters from these “fringy insular subcultures,” all trying to find ways to live — and also ways to save themselves and others, like you and your friends wanted to do. How did you curate your subjects?

As potential subjects came into my field of view, I would say 99% of my selection was based on what I felt I could maintain interest in. There were a lot of other candidates that I didn’t end up writing about, who were doing things that were maybe more demonstrably effective on paper. Like, you could run a study on what they were doing. But that’s for another writer, not for me.

What’s more interesting to me is how people make beauty and meaning from their lives, maybe especially if they’ve had a tough go. So the only people that ever held my attention were people who came with the whole package. Everybody in the book comes with a whole worldview. Even John D. Liu, the land restoration expert, has this whole ethos around restoring the Garden of Eden and how it’s our birthright to regenerate the planet.

So, the subjects are trying to figure out how they interact with the world in terms of measurable impacts, but they’re also asking big, spiritual questions: What’s our history, and how do we make sense of that history? What’s our duty to future generations? What kind of addiction or sickness is preventing me from forming real relationships with the place where I live and also with other people? How do I resist the influence of empire, and how do I really resist everything I’ve ever learned?

It strikes me that for many of your subjects, answering those questions requires outcasting themselves from mainstream society, some of them in dramatic and absolute ways, like Finisia Medrano, the trans rewilder who led a group of “nomadic gardeners” in the Oregon-Idaho desert.

Did you see any personal qualities that differentiated your subjects — people willing to make this kind of sacrifice — from people like me, who might be concerned with impending doom, too, but still operate within this destructive society, pretty caught up in our daily to-do lists?

I think there are a number of paths to the edge. Finisia is a great example of a person who was unable to conform. She was too much herself from the beginning. Some of that had to do with structural inequity — we could certainly look at it through that lens — but some of it probably had to do with temperament, and some of it probably had to do with trauma.

It’s a question about what it takes to want to live in a way opposite from the culture that you were born into. This isn’t a problem if you’re born into a culture where every aspect of your society is organized around giving life to the planet. In that case, you don’t have to learn a new way to be. You might have to fight outside forces that are trying to impede or destroy your way of life. But it’s a different thing to be born into a culture as a social creature that has abstracted the cost of your life — where everything is pulling you towards continuing numbness and abstraction.

I think everybody ends up heading in the direction in which they’re being pulled, to an extent. I don’t want to undersell the sacrifice any of my subjects made in choosing to live in the ways they do, but I also think there’s no point in beating yourself up over it if you haven’t followed a life of extreme asceticism. Of course we have free will, but the forces that shape our will are also predetermined by our life circumstances, which is why the Christian cosmology maps so neatly onto these questions.

I’m not surprised that Christian themes keep coming up in this conversation, because they also permeate the book — right from the epigraph, which is a quote from a Charles D’Ambrosio short story, in which a nun tells a student “The opposite of love is despair.”

Some of the subjects are Christians, like the cooperative community engaged in watershed discipleship, and even Finisia in her own way. Why do you think you found yourself reaching into the Christian paradigm so frequently in your meaning-making and imagery?

There’s a lot of Christianity in the book, not because I’m partial to Christianity, but because I live in a country that is permeated with that mythology, even among non-religious folks. These symbols and ways of relating to good and evil — we’re all kind of living these metaphors, whether we know it or not. It’s just part of living here.

What’s exciting about it to me is all of these people are taking the mythology they’ve inherited and reinterpreting it and understanding the metaphors differently, in ways that can help guide them through this time of crisis and transition. I mean, they would say they’re understanding the metaphors as they were intended. I wouldn’t say that, because who knows? It was thousands of years ago.

To me, a story and spirituality should serve the people that are practicing it. Otherwise, it’s useless. It’s a symbol drained of power. So it’s kind of amazing that they’ve been able to resurrect — to use the central metaphor of their religion — that they’ve been able to resurrect these stories in such a way that the stories have power again. It’s not just like somebody reciting something in a church while everybody snores in the pews. These are metaphors that actually pertain to your life and survival.

You describe the central question of your book as an “impossible” one. What did it feel like to dedicate yourself to the impossible while writing this book?

Well, what I’ll tell you is it was really hard, and it was hard for a number of reasons. It seems sexy to say you’re writing about people living “off the grid,” but the reality of the stories is that these people are trying and failing beautifully to reckon with really painful aspects of existence that are actually not very glorifiable.

I almost feel like my experience of writing the book parallels the experience of the people I wrote about. It’s as if I asked for it, without knowing it — I asked to be kind of ridden by these forces, and I naively jumped into these questions that are, if you’re honest, unanswerable. If you’re willing to really grapple with the question, there are no easy answers, and it’s a hard place to live for six years. I can’t imagine what it’s like to live with them for decades, like the people I’ve written about.

A lot of these visionary individuals and the small, localized efforts can be easily critiqued as insufficient in the face of the challenges humanity is facing — which many of your subjects are the first to concede.

But in their totality, these essays point toward value and beauty in their work. I’m wondering what you see as the value in the projects undertaken by your subjects, or maybe how you think Peter might articulate the value?

I’m glad you asked me how Peter would describe the value, because I don’t know that I have a good answer for that. I think he’d say that these efforts are torches being carried through the dark of history. One day, these skills are going to be necessary if anyone should survive. If we live on a habitable planet that includes human beings, even in a changed landscape, human beings are going to need these skills. It’s a leap of faith, to dedicate yourself to restoring a world you won’t live to see.

That’s one answer, but I think Finisa would have said something different. I think she’d say this is what she does in order to have any sense of conscience and to not be a total bullshit artist. While I don’t align with all of Finisia’s ideas about right and wrong, I do think her belief is adjacent to some of what I believe. I believe most of us are experts at lying to ourselves about the cost of our lives. There are all kinds of ways to dodge real awareness of that cost, but one way is by deflecting your own responsibility by focusing on the misdeeds of others. The only way groups change or societies change is if individuals change, and individuals are in turn shaped by societies — it’s not one or the other. And individuals don’t change their relationship to the planet by talking a bunch of shit on social media, you know? There feels to me to be a real absence of connection to place — at least connections that go beyond a nature journal. What does it mean to put your blood in the ground, and to bury your dead in the same place, and to feed your children from your own garden? Everything in the culture is pulling us away from that kind of relationship.

To circle back to the question of impact, I do think it’s important to learn how to live as individuals in smaller communities in light of climate catastrophe, not because that’s necessarily going to alter the trajectories of these but feedback loops, but because this is our future — if we get to have one. The train is off the rails. We’re all going there anyway. Certainly, it would be better if it were a softer collapse. But the change is a foregone conclusion.

Instead of ending our conversation with collapse, let’s end it by talking about language and poetry, which many of us seek out as another type of torch in the darkness.

Your last book, The Fix, is a poetry collection. How would you say your poetic sensibility informed your essay writing?

I do like to attend to the music of a line. Not every line — that’s too much. That gets irritating to the reader. But every once in a while, I like to just make something rhyme internally or add some kind of extravagant alliteration, only because it pleases me. Not because it necessarily adds to the text. Certainly, if it detracts from the text, I’ll cut it. But I think the impulse springs from a poetic sensibility. You’re producing something that creates an experience. The pleasure is justification enough for it to exist in the book. It’s like, why do you wear earrings? What purpose do they serve? Well, they’re beautiful, and they make you feel great. It’s the same with attending to sound. It’s for beauty’s sake.

Believers

Believers

By Lisa Wells

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

July 2021

Alex Madison is a writer based in Seattle. She interviews authors for Bookforum, The Millions and elsewhere.

This post may contain affiliate links.